Two of Texas’ major cities – although drivers of the state’s economic miracle – have been brought to their knees by ever-increasing public-sector worker benefits.

According to Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings, the city is teetering on the edge of bankruptcy. Moody’s, one of the premier credit rating agencies, recently reported that the city now owes the largest pension liability out of any major American city except Chicago, when compared to its resources.

Houston is doing marginally better, but is heading down the same path if substantive pension reform doesn’t come soon.

For years, attention has been rightly given to Houston’s massive unfunded pension liabilities. There have been op-eds and position papers calling the city to either reform or face bankruptcy. Unlike Houston however, Dallas’ crisis has largely gone unreported, despite more immediate urgency.

Now Dallas is back in the spotlight, as its police-union members started to make a run for their pension benefits, exacerbating the already precarious fiscal state of the city.

The trouble with Dallas hit the news in September when members, perceiving a potential threat of new regulations regarding benefit withdrawals, all began withdrawing their deferred retirement option plan, or DROP, benefits.

DROP is embedded into many public-employee benefit plans. The program allows employees to continue working after the date they would be eligible to retire, but instead of collecting or continuing to accrue pension benefits, the employee has a sum of money credited to a DROP account. The tax-deferred, interest-bearing DROP account is paid out in addition to the employees’ earned benefits. Like most municipal assumptions, the DROP rate of return is typically set at a higher rate than what the market can actually offer.

In other words, similar to their pension benefits, DROP contributions are often untenable, unfunded promises hoisted on the backs of future taxpayers.

Dallas public employees’ DROP accounts “guaranteed” a tax-deferred rate of return of 8 percent, until October 1st which is when they planned to adjust it to a more realistic (but still high) 6 or 7 percent. The adjustment caused many employees to run for their benefits and start requesting DROP payments, although the plan only had enough assets to pay out 45 percent of future benefits.

In other words, the DROP account was underfunded by 55 percent.

Within six weeks, Dallas had to pay out $220 million in requested DROP payments with another $82 million requested since September 21st. At the current rate, the plan is looking at insolvency by 2028, which is why the pension funds have asked the city for a $1.1 billion bailout to keep it afloat. This staggering figure is equal to the size of the city’s entire general fund, or what the city would spend on core services over an entire fiscal year.

The rate reduction and loss of assets came because Dallas pension managers invested funds into high-priced real estate in places like Hawaii, Paris, and Abu Dhabi, as well as other volatile assets. Managers who were tasked with chasing an unrealistic rate of return invested in riskier assets.

Out of 150 plans researched by the Public Plans Database, Dallas had the highest percentage of assets in real estate. The faulty investments resulted in a staggering $525 million loss between 2013 and 2015.

The underlying problem with many of Texas’ urban municipal plans is that they are locked in state statute, at the request of local lawmakers and public-sector unions. This means that major reforms can only happen once every two years when state lawmakers are in Austin, within a 140-day period.

This requires pension and local officials to come together and go to the legislature to ask for changes. Local officials need the ability to adjust these plans regularly, on their own timeline, but with oversight since most of them are more than happy to delay a solution until they are no longer in office.

Even worse, there is no political appetite to standardize how these plans operate. Experts have repeatedly called for Houston’s plan to switch to a defined-contribution model, similar to private companies, but public-sector unions oppose this idea.

State Rep. Dan Flynn (R-Canton) had a bill filed on behalf of Houston’s mayor which keeps the defined benefit model intact, and embeds adjustments in state statute. On the other hand, when it comes to Dallas’ pension plans, Flynn said that a defined-contribution option is not off of the table.

It’s odd that he would keep a plan switch on the table for Dallas, because of the unstable position it is in, but not make an effort to put that plan on the table for Houston, in order to prevent Houston from following Dallas’ disastrous path. His position essentially says Houston needs to be even worse off before substantial reform should take place.

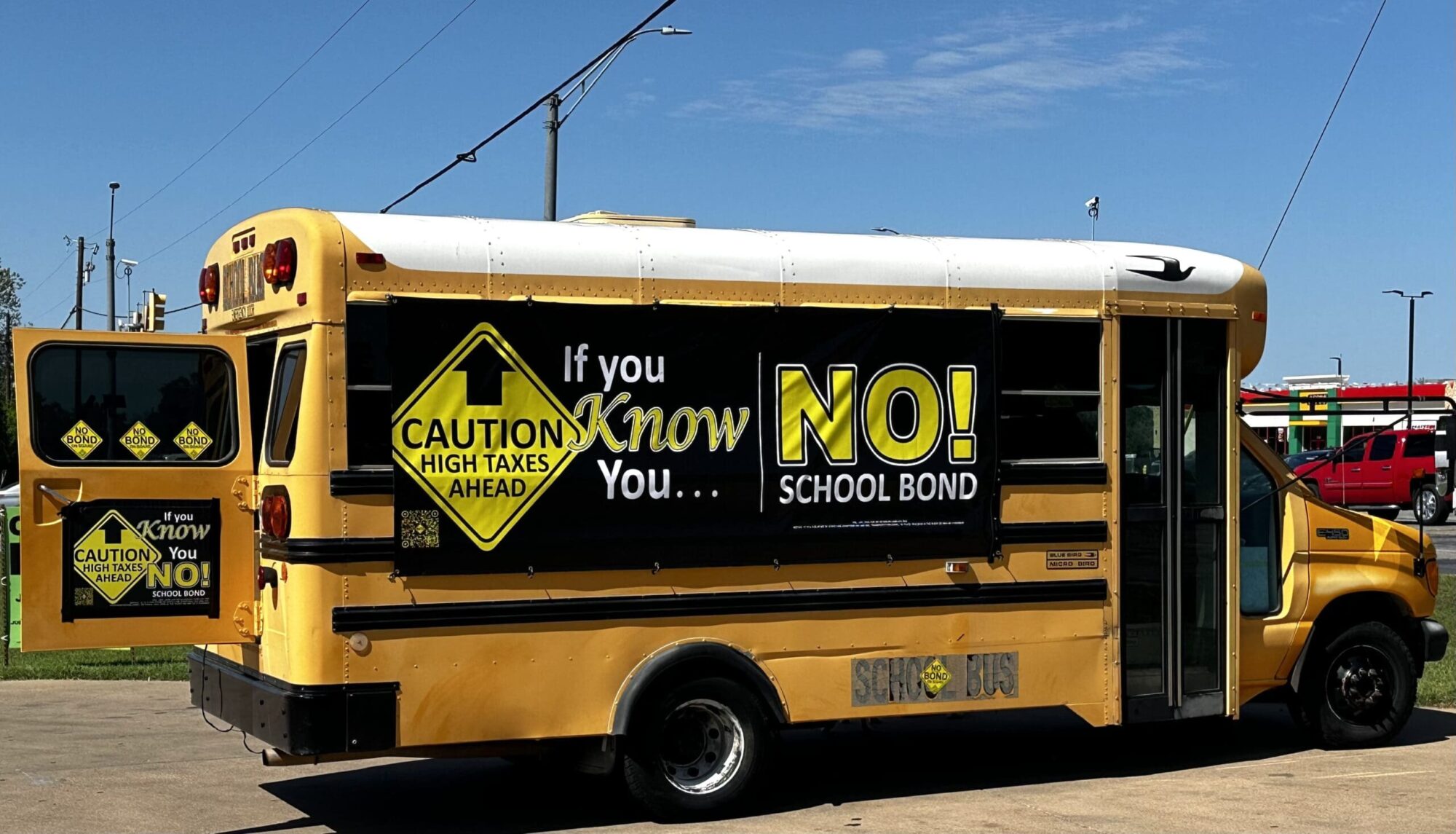

Luckily, State Sen. Paul Bettencourt (R-Houston) has filed numerous pro-taxpayer and pro-pension reform bills. One would require voter-approval on pension obligation bonds, while the other would restore control and accountability to locally elected officials.

DROP coupled with other lucrative benefits such as 4 percent cost of living increases, massive payouts upon retirement equivalent to an employee’s highest paying years, and a refusal to switch from defined-benefit to defined-contribution plans are what’s choking cities and leaving taxpayers with few reasonable options.

Staying the course has the possibility of taking down Texas’ two powerhouse cities. Texas’ pension crisis is no longer a hypothetical one.

The decision before lawmakers is clear; either appease unaccountable local officials and the unions that helped to create the crisis, or support common-sense reforms that restore pension solvency and protect Texas taxpayers.