Exorbitant property taxes continue to torment Texans, pushing people out of their homes and making homeownership a distant dream for the young.

“Currently, Texas ‘boasts’ the sixth highest property tax burden in the United States. Property taxes themselves have increased 181 percent in the last 20 years alone, despite promises from Republican lawmakers to address the issue,” Tim Hardin, CEO of Texans for Fiscal Responsibility, wrote in the organization’s Texas Prosperity Plan.

As it currently stands, it would appear the system is rigged to keep citizens’ tax bills rising and local government bank accounts swollen.

A particularly brazen example of this dynamic can be seen in Tarrant County, where a government bureaucrat targeted a citizen who helps homeowners fight their rising property tax bills for free.

Records show his supervisor was aware of this since at least November, but for months, he did nothing.

Property Taxes: A Burdensome and Opaque System

Most local governments in Texas—cities, counties, school districts, and more—acquire money by taxing homeowners. This continues regardless of whether the property is paid off or not.

Like at the federal and state levels, local taxing and spending over time has far exceeded the need to provide core services to citizens.

A study by the Texas Public Policy Foundation (TPPF) found that from 2009 to 2019, Texas’ total property tax burden exploded by 199 percent. Since the state’s population and inflation had grown only by 109 percent, TPPF found these tax bills had grown “faster than the average taxpayer’s ability to pay for them.”

Furthermore, in 2020 the Tax Foundation reported the Lone Star State ranked seventh in oppressive property tax on homeowners and 15th for businesses.

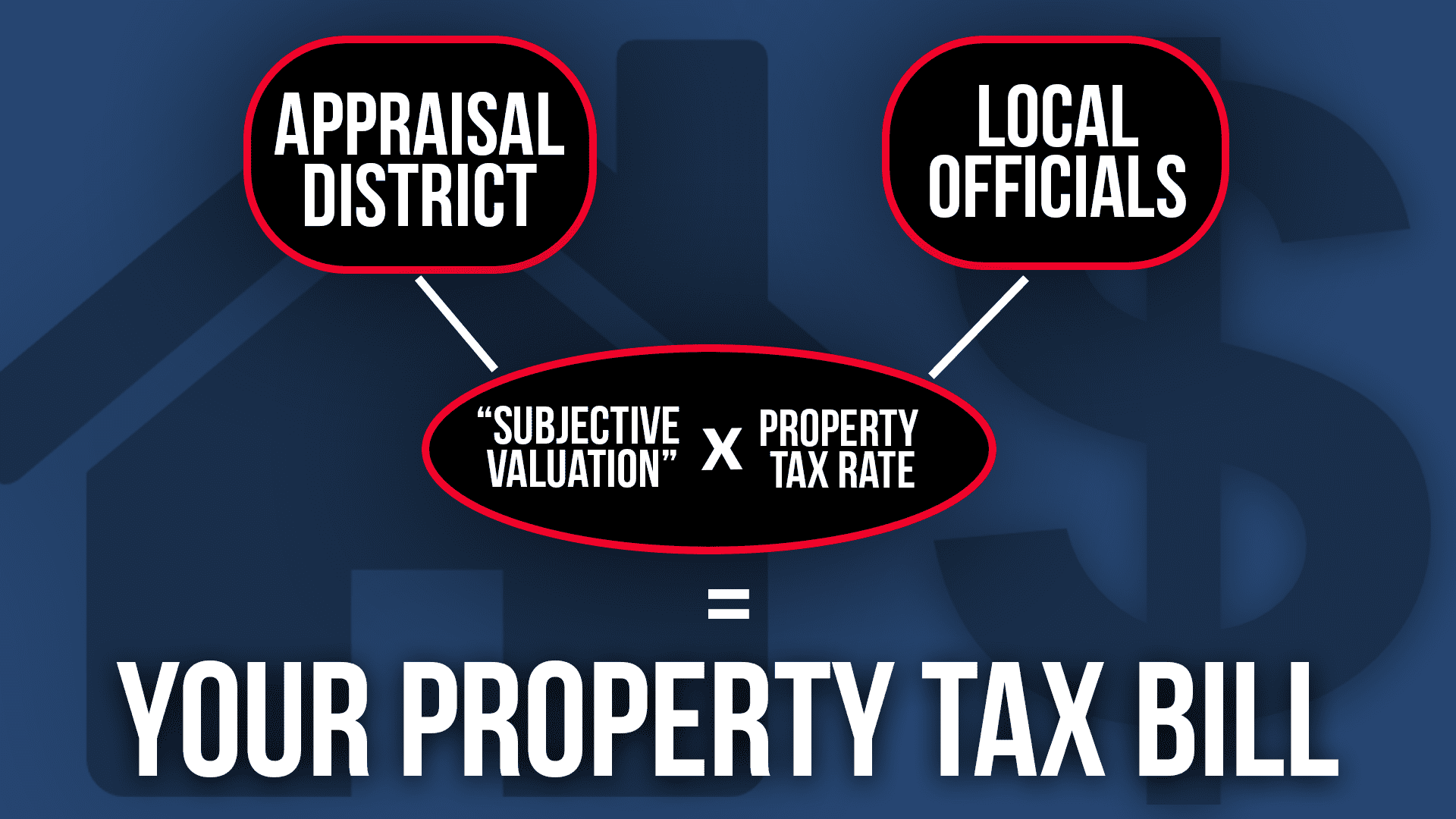

How these tax bills are set annually is nearly as burdensome as the bills themselves, and the two-part process is opaque.

The first part of the process involves setting the taxable value of a property by its local appraisal district, whether it is a home, apartment complex, office building, or farmland. TPPF states the numbers these districts set are “subjective valuations.”

The second part involves local public servants: city council members, county commissioners, school board trustees, etc. Every year, they decide how much of your money they want to spend, then they set a property tax rate so they can spend that amount.

This process has been criticized, as local officials set these rates “with little to no feedback from citizens.”

In order to stop, or at least control, the growth of these tax bills, homeowners must insert themselves in the process. To lower their home’s taxable value, homeowners must appeal the subjective value of their home set by the appraisal district.

Renters do not have this option. While property taxes affect their monthly payments, since they do not own the property they rent, they cannot protest the taxable value.

Citizens can also take action by pressuring their city council members, county commissioners, school board members, and other local public servants to adopt the no-new-revenue rate (NNRR). This is the property tax rate that would, if adopted, keep tax bills roughly the same year to year despite any changes in a property’s appraised value. Individual results may vary.

In order to lower your tax bill from the previous year, your local governments would have to adopt a tax rate below the NNRR.

The subject of this article necessitates focus on the appraisal district side.

The Marsh of Protesting Property Values

Appealing property values to unelected bureaucrats is a different monster than getting elected officials to heed you.

“The best way that I’ve been able to describe this to somebody that has no knowledge of this whole system … [sic] [is] the tax protest process exists in an alternate universe,” said Chandler Crouch, a North Texas realtor. “They redefine terminology to mean something different than its common, everyday usage, and the valuation methods are different from what you would use in common, everyday practice.”

According to attorney Melissa Lowery Gallagher of the Gallagher Firm, there’s also a question of justice. Half of her firm’s work is on property taxes, specifically in residential Tarrant County.

“At the administrative level, the amount of justice you can expect to receive is lower than if you appeal and take your case to district court,” she told Texas Scorecard. Gallagher notes that property owners can do administrative appeals themselves for free, but sometimes the district court is the only place to find justice—and your costs go up dramatically there. To help, Gallagher has been offering pro bono services for these kinds of appeals to those with the over-65 age exemption; she hopes to roll out these services for low-income neighborhoods in the future.

“People that are living in low-income neighborhoods, they can’t afford that level of justice.”

She also believes there’s a lack of sustainability in the system. “There’s hundreds of thousands of properties that have to be valued by a certain date, and there’s some logistical issues with trying to get that while maintaining protests,” she said. “How logistically possible would that be if everyone went to a hearing?”

It’s in this “alternate universe” that Crouch has been helping homeowners in Tarrant County try to obtain justice.

A One-man Army for Property Taxpayers

Having lived in north Fort Worth with his family since 2007, Crouch wanted his real estate company—Chandler Crouch Realtors—to do more than “just business.” He also wanted to serve.

Crouch found the greatest need was helping homeowners protest their appraisals. “People are getting taxed out of their homes,” Crouch told Texas Scorecard. “Our property tax system is broken.”

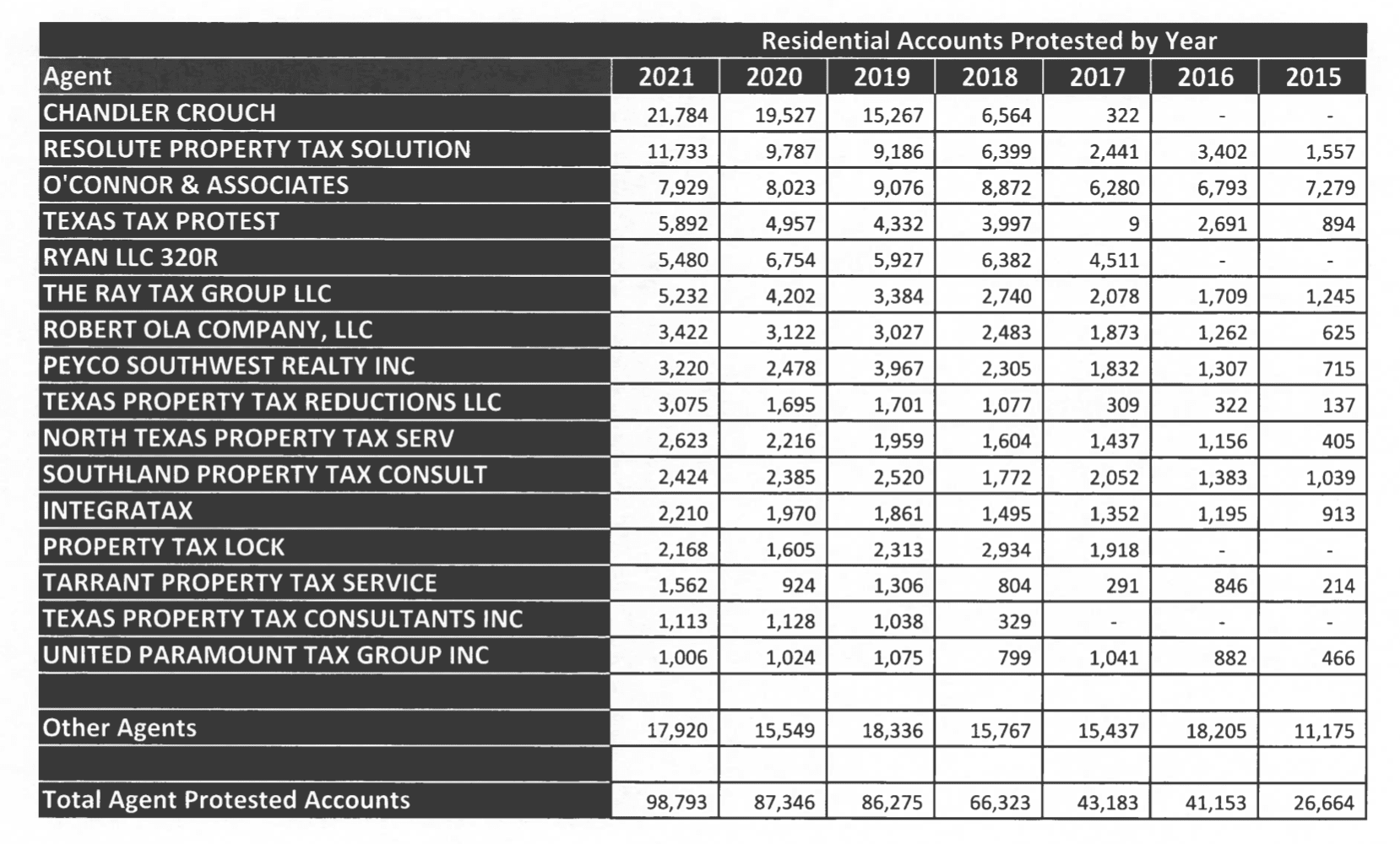

Steadily, Crouch has been making a difference. Internal records of the Tarrant Appraisal District, obtained through an open records request, compare the scope of his efforts compared with others’.

In 2017, he served 322 homeowners. In 2021, he helped more than 21,000—far more than any other property tax agent in the county.

And Crouch does it all for free. He says the only financial benefit is the hope that those he helps will consider his real estate company when they’re in the market to buy or sell.

For contrast, we compared his service with Property Tax Protest, a company that protests values in nine counties across Texas. They charge 1 percent of the reduction you receive in your home’s appraised value as a result of their work. So, if they decrease your home’s appraised value by $50,000 (an amount they used in their example), you pay them $500.

If $50,000 is the average savings per home, then Crouch gave away more than $10 million worth of services last year.

But how can his team handle thousands of protests effectively, while charging nothing? “I take a systematic approach, and I have an incredible team,” Crouch said. “And I usually work many sleepless nights.” He also leverages his understanding of Texas’ Property Tax Code, the Tarrant Appraisal District, and his working relationships with people there.

But this only controls the growth of property tax bills, and Crouch is committed to solving the property tax problem permanently. He worked closely with outgoing State Rep. Matt Krause (R–Haslet) to advance property tax reforms in the state Legislature.

He also helped educate and empower citizens to become involved in the complex and opaque election that decides who sits on TAD’s board of directors. Citizens don’t have the option of voting in this election, but they can indirectly make their voice heard by contacting those who do (city council members, county commissioners, and school board trustees countywide). Thanks to Crouch’s efforts, citizens rocked the 2019 TAD board election.

Taxpayers are grateful.

“Chandler Crouch and his team are BOSS,” wrote Francesca of Fort Worth. “[He] helped us lower our property tax significantly.”

“Chandler is just one of those rare people that believes in helping others at any cost,” stated Julie McCarty, CEO of the statewide citizen activist group True Texas Project. “He is motivated by doing the right thing simply because it is the right thing.”

But not everyone appreciates his fighting for the taxpayers.

Bureaucrat Targets Crouch

On November 1, 2021, Crouch received a letter from the Texas Dept. of Licensing & Regulation stating a complaint had been filed against him and he was under investigation.

That letter contained three complaints; they allege that last year, Crouch had “intentionally misled members of the Tarrant Appraisal Review Board” (TARB) when he protested values assigned to properties by TAD. In one case, it alleges he also misled “Tarrant County taxpayers” and is making a “mockery of the current tax system.”

Nowhere in the document did it identify who filed these complaints.

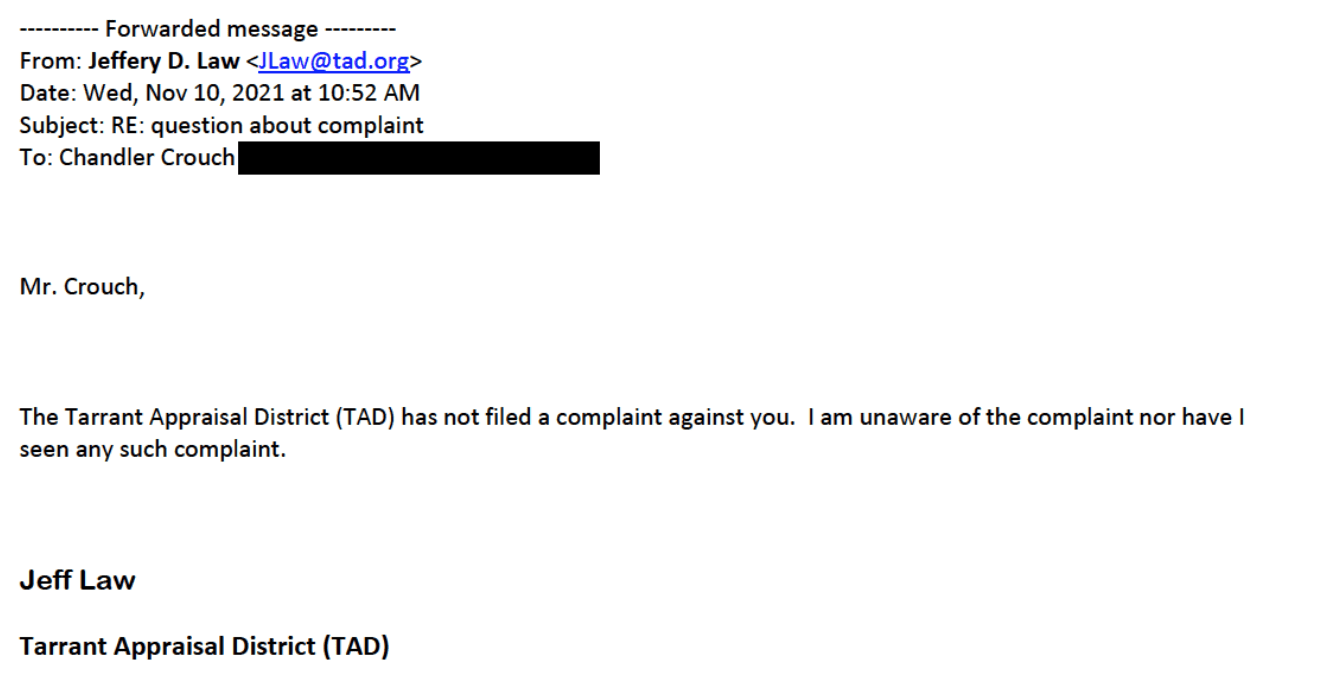

Crouch told us he contacted the assigned TDLR investigator, Robert Nino, who initially said TAD had filed the complaints. Crouch contacted Jeff Law, TAD’s executive director and chief appraiser.

Texas Scorecard reviewed correspondence Crouch received from Law on November 10, 2021.“The Tarrant Appraisal District (TAD) has not filed a complaint against you,” Law replied via email. “I am unaware of the complaint nor have I seen any such complaint.”

Following this reply, Nino admitted Randall Armstrong, the director of residential appraisal at TAD, had filed the complaint.

After Texas Scorecard learned of this investigation, we sent TDLR an open records request and received in response their 75-page investigative file on Crouch, as well as Nino’s summary report. Within this file are four complaints Armstrong made against Crouch.

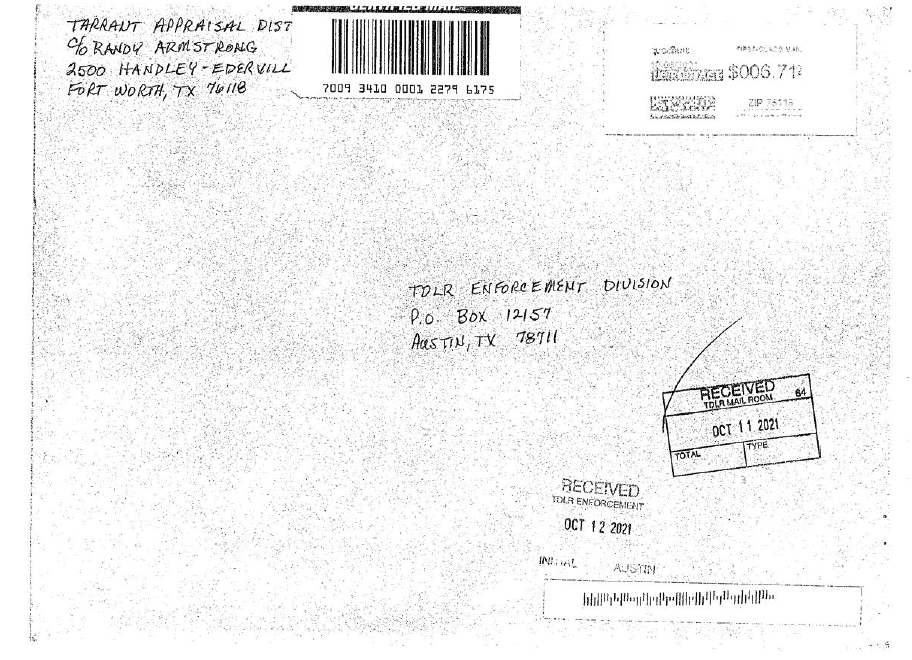

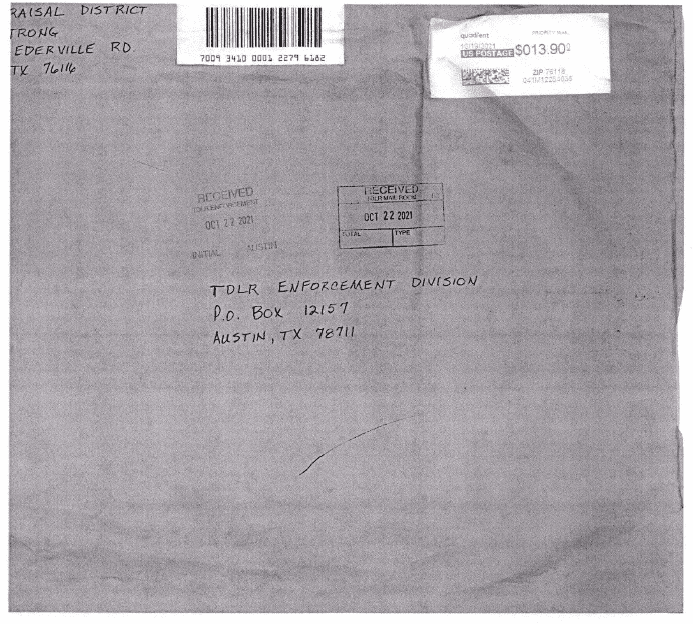

These files not only confirmed Armstrong had filed these complaints, but it appeared he had done so in his official capacity as a TAD employee. Three mailings (pictured below) feature Armstrong using TAD’s business name and address.

While an open records request failed to determine whether taxpayers had paid for these mailings, we did learn Armstrong had signed at least three complaints using his official title.

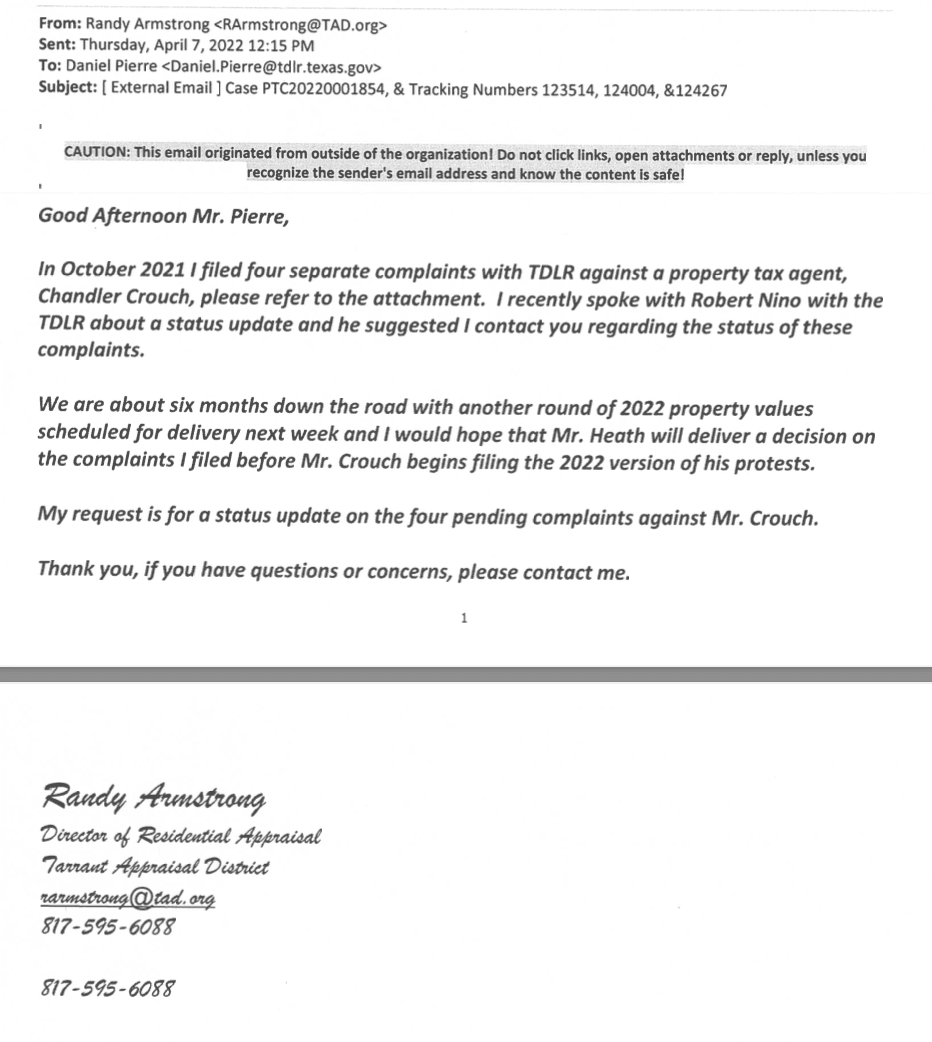

He also communicated with TDLR using taxpayer funded resources: his TAD email address. He signed his emails in such a fashion that made it appear he was acting in an official capacity on behalf of TAD. See below his April 7, 2022 email to TDLR asking about the status of their investigation. He was told no determination had yet been made.

“The fact that he put Tarrant Appraisal District in the signature block is concerning to me, because it appears on its face that he was acting with apparent authority of the Tarrant Appraisal District, which was later then shown that he was not,” Gallagher said, pointing to Law’s reply to Crouch.

She also was concerned about how Armstrong had obtained the records he sent to TDLR with his allegations. “If he obtained [them] while he was acting in his capacity as an employee of the district, and he did not obtain this via [a] public information act request, there’s a big conflict there.”

Texas Scorecard sent an open records request to TAD, requesting any such requests from Armstrong to the district regarding the properties he listed in his complaints that occurred in 2020 and 2021. “The district has no records responsive to your PIA request,” TAD replied.

Records show Armstrong’s first complaint was filed online with TDLR on October 5, 2021, with a timestamp of 3:19 p.m. Records from TAD show Armstrong worked eight hours that day and first entered the building at 7:54 a.m.

The second complaint was filed on October 19, 2021, with a timestamp of 3:06 p.m. TAD records show he worked 6.5 hours that day, with 1.5 attributed to sick leave to help his mother. Records show he first arrived on TAD property at 9:31 a.m.

It’s unclear from TDLR records when the third complaint was filed. The fourth and final complaint was filed on December 22, 2021, with a timestamp of 11:36 a.m. TAD records show Armstrong worked eight hours that day and first entered TAD at 7:53 a.m.

As for the status of TDLR’s investigation into Crouch, Aaron Heath, a prosecutor in TDLR’s enforcement division, told Texas Scorecard on May 11 that this is “an active case.”

While shocking, this conflict between Armstrong and Crouch has been a long time coming.

Who Is Randall Armstrong?

Conflicts of interest are nothing new for Armstrong.

While working at TAD, Armstrong had been a board trustee since 2007 at White Settlement Independent School District, west of Fort Worth, and had been board president since 2012. Therefore, Armstrong not only was involved in deciding the taxable values of taxpayers’ homes at TAD, but he was also involved in deciding tax rates for homeowners within White Settlement ISD, which is in Tarrant County.

This had been legal for years in Texas, until when the Texas Legislature in 2019 passed Senate Bill 2, which included a provision banning these conflicts of interest. State Rep. Krause (R–Haslet) said the provision was added in from his own House Bill 1333, and he credits Crouch for this and other property tax reforms they worked on together.

“His knowledge and expertise of the system, having done so many of those [protests], is what led to those ideas,” Krause told Texas Scorecard.

Citizen Daniel Bennett, who has had dealings with Armstrong and helped uncover this conflict of interest, has also been credited for helping get this reform passed.

It was widely reported that, despite the new law, Armstrong was not going to resign as school board trustee.

In a December 2019 email exchange with Crouch, Armstrong disputed this, saying his quote had been “as of now, (comma) I don’t plan to resign.” He then informed Crouch of his intention to resign, which he did on December 17, 2019.

But he was bitter. “I owe no one an apology for serving and giving back to the community that helped raise me; but thanks to your group, I continue to be villainized and dehumanized because I work at TAD,” Armstrong wrote Crouch. “I’m not sure what your end game is or what your motives are, but I hope that all the criticism and attacks that you are party to wind up serving you well … but I’ll leave that to your conscience.”

He also may have given Crouch a preview of his plans next year. “The conflict of interest issue that your group continues to trumpet about my situation is no more a conflict of interest than your personal situation as a realtor and a critic of TAD.”

Confrontation

On May 12, 2022, attorney Frank Hill, representing Crouch, sent a letter to the TAD board of directors.

“Indeed, if your governmental entity is seeking to impose restrictions on our client’s free speech in dealing with these matters of public concern and importance, we view it as a plain violation of his First Amendment rights,” Hill wrote. “We feel certain that you are not aware of such efforts and that you will not tolerate such efforts once they are brought to your attention.”

On June 10, Crouch confronted the TAD board at their regular meeting about Armstrong’s complaints. “There’s a real question as to who filed that complaint,” Crouch said. “Was it the Tarrant Appraisal District? Was it Randy Armstrong? How much does Jeff Law support this complaint?”

He also said there’s a problem regardless of whether he is innocent or guilty of the allegations, due to the five years he’s worked with TAD employees throughout the protest process.

“If I’m guilty, there are an army of people here that are guilty as well, and there’s a big problem that somebody didn’t speak up until this complaint was filed,” he said. “If I’m innocent, what is the Tarrant Appraisal District ok with? Are they ok with the fact that somebody filed that complaint knowingly? Did Mr. Law know that this complaint was filed?”

“The Tarrant Appraisal District did not file that complaint,” said Matthew Tepper, the board’s attorney. “I understand from Mr. Law, nobody who had the authority of the appraisal district to file the complaint did it.”

Law, for his part, appeared to contradict himself. “I have not seen the complaints. This is the first time I’ve actually seen a portion of the complaint,” he said after Crouch handed out documentation.

He later changed his answer, saying it wasn’t until open records requests had been filed he learned the TAD address had been used on envelopes to TDLR, and that Armstrong had signed them “Director of Residential Appraisal.”

“It was my understanding at that particular time that Mr. Armstrong had filed the complaint solely on his own, as an individual,” Law said. “I still have not read the complaint, other than fulfilling a public information request.”

“I did not direct Mr. Armstrong to file a complaint against you,” he continued.

Crouch told board members he had made Law aware of what was happening back in November. “To me, the lack of action on this implicates the Tarrant Appraisal District.”

To that end, Tepper made it clear where accountability lies for the actions of TAD employees. “Mr. Law is responsible for managing and overseeing the employees of the appraisal district,” he said. “This board manages and oversees Mr. Law.”

The board decided to discuss the matter in closed session at their next meeting, two months from now. “The appraisal district is involved in this. We don’t know to what [extent],” Chairwoman Kathryn Wilemon said.

When Crouch asked if Law’s lack of action was a concern to the board, Wilemon replied they would discuss it during the closed session.

Board members Tony Pampa and Rich DeOtte suggested Law investigate the matter. “I’d be happy to try and get to the bottom of it,” Law told DeOtte.

This article was updated to correct the year the Tax Foundation’s report was published.