Citizen backlash against the “defund the police” movement in Texas was so strong, Gov. Greg Abbott made stopping it one of his emergency items for the Texas Legislature. However, citizen involvement at local and state levels is required for true accountability and to make sure the Legislature provides a real solution, rather than make things worse.

Last year, the Austin City Council voted to defund its police budget by $150 million, spending taxpayers’ money elsewhere. A majority of Dallas City Council members voted to cut $7 million from their police overtime budget; the original plan was to spend that money on other projects like bike lanes and solar power, but citizen backlash forced the council to use most of the funds to moving more police officers from desk work to patrol.

No other major city council in Texas followed Austin and Dallas. Citizen backlash against the “defund” push was significant, as crime last year skyrocketed statewide.

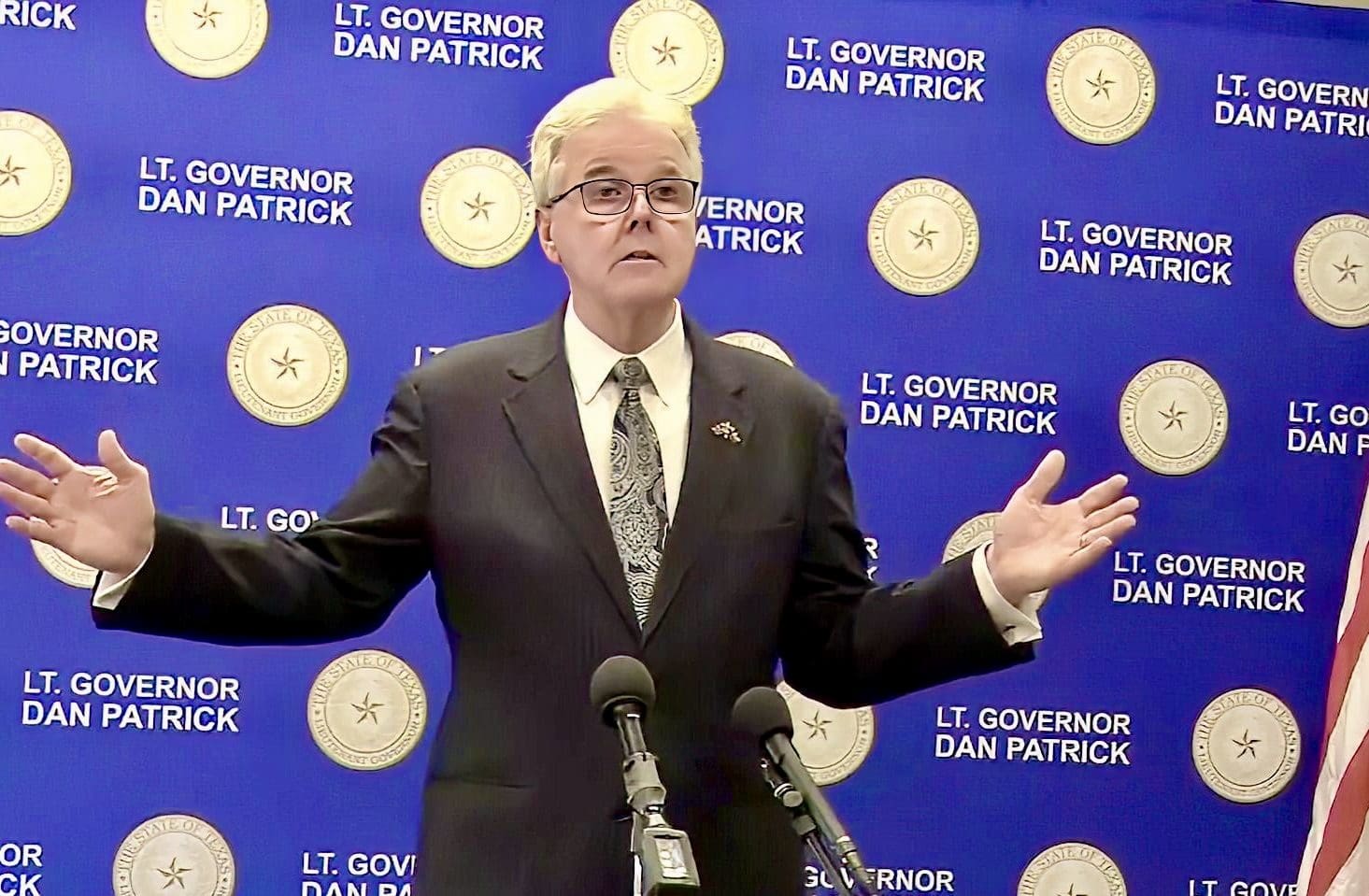

In February, Abbott made preventing “local defunding of police” an emergency item.

To discover what such legislation may look like, and what hurdles must be navigated, Texas Scorecard interviewed Charles Blain, president of Urban Reform and the Urban Reform Institute, and Derek Cohen, director of Texas Public Policy Foundation’s criminal justice reform campaign Right On Crime.

What is “Defund the Police”?

“The left seems to have defined ‘defunding police’ as taking resources from traditional policing and redirecting them to, for the most part, efforts that they consider the drivers of crime: mental health, homelessness, and poverty,” Blain said.

Cohen largely agrees.

“The left defines ‘defunding the police’ as ‘subtract $X from the police department’s budget’ and, for the more thoughtful types, spending that money addressing the ‘root causes’ of crime,” Cohen said. “However, the ‘root causes of crime’ often barely correlate, and instead tend to represent other progressive spending desires.”

Cohen also mentioned the left’s linking of the “defund the police” movement to the tragic death of George Floyd.

“Worst of all, they tend to say they wish to defund the police so incidents like that which happened to George Floyd do not happen again,” he continued. “In truth, defunding departments will make them far more likely to occur.”

“From an observer’s perspective, citizens who live in high-crime, often impoverished areas are not supportive of the idea and aren’t the ones calling for it,” Blain added.

“Citizens have rightly rejected the defund movement in opinion polls and at the ballot box,” Cohen stated.

What can the Legislature do?

“I’m not really sure,” Blain said. “But I know … that the Legislature throwing a blanket ban on defunding without specifically identifying what they mean by that would open a new can of worms.”

“I’m not sure what can be done outside of usurping law enforcement authority from municipal governments that behave poorly, but that too introduces a completely different set of issues,” Cohen analyzed. “The best remedy for chronic municipal mismanagement would be a robust disannexation option where a neighborhood, precinct, etc. could vote themselves out of the municipality.”

What about Austin and Dallas? As of publication, those cities haven’t walked back their actions. Could the Texas Legislature make them?

“Short of mandating them to do so, I’m not sure what tools they have,” Blain said. “If they really wanted to see a different outcome, state lawmakers should have been, and should be, more in tune with what the local governments in their districts are doing.”

These lawmakers had a right, just like everyone else, to show up, testify, and oppose the moves when they were coming through city halls.

Cohen advocates for citizens to get involved, as well.

“First and foremost, the voters can act,” he said. “The council member who championed the police defunding and chaired the public safety committee [in Austin] was recently voted out.”

Fiscal Responsibility?

One possible risk is that Texas legislative action could make it difficult for local officials to make genuine efficiencies—ones that wouldn’t negatively affect the quality of service—in their police budgets.

“That’s my primary concern with a ban on defunding the police,” Blain pointed out.

“I think you hit on an important point,” Cohen agreed. “I would be stunned to find out that any municipal agency, police or not, is funded right at its true optimal point, right down to the very cent.”

Cohen points out the reality is the state of a police department varies from city to city.

“Some departments certainly do have some fat to trim; others are underfunded,” he continued. “Both realities need to be taken into account when crafting a policy that affects all departments in the state. You would also have to account for the wide variation in services that local communities want to see their police do.”

Quiet suburbs and major metro departments do not have the same complement of services.

There’s also the question of property taxes. Could the Legislature give local officials an excuse to keep hiking them, or can they craft a law to avoid that?

“I’m not sure how it can be avoided. But if you ban cities from reducing budgets, the only other option is that they increase them even more than they currently are,” Blain observed.

“I’m not sure local governments need much of an excuse to hike taxes,” Cohen exclaimed. “I could see a push for ‘core functions’ to be exempted from SB 2 [2019’s property tax reform law], but you know as well as I how fungible money [is] in municipal budgets.”

If progressives believed that the mission of the police was too broad before, just wait until the function gets a pass from reasonable spending restrictions.

Call to Action

The Legislature is in session through May, and the deadline to file bills is this Friday, March 12. What should concerned citizens do about this issue?

“Learn about it—from multiple sources—and engage conscientiously,” Cohen advised.

“Engage at the local and state level,” Blain added. “Too often, organized progressive groups are the ones claiming to speak for citizens in cities. Show legislators and council members that’s not the case.”

Concerned citizens may contact their state representative and state senator. Filed legislation may be tracked using Texas Legislature Online.