Texans demanding more action to tackle voter fraud gained a new ally last week: the state’s top policy institute.

On Friday, Texas Public Policy Foundation announced it is launching an initiative to combat election fraud in 2020. The news came on the final day of the think tank’s annual policy orientation.

At @TPPF’s #PO2020 @KevinRobertsTX announces TPPF’s new initiative to combat election fraud in Texas in 2020, citing the importance of “Rule of law” in the maintenance of the American republic. pic.twitter.com/piJ0Zrmr2X

— Chuck DeVore (@ChuckDeVore) January 24, 2020

Executive Director Kevin Roberts didn’t share specifics of the plan, but on Thursday, TPPF premiered a video highlighting election corruption and voter fraud in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, including illegal mail ballot harvesting, vote-buying, voter intimidation, noncitizens voting, and corrupt officials.

Election fraud isn’t isolated to South Texas, says Omar Escobar, a district attorney from the region who is featured in the video; in fact, it’s happening all over the country, adds national election expert J. Christian Adams. Their remarks in the video and a panel discussion that followed its debut may signal which direction TPPF’s election integrity initiative will take.

Escobar and Adams both have hands-on experience fighting voter fraud in Texas—Escobar as chief prosecutor for Starr, Duval, and Jim Hogg counties in the RGV; Adams as head of the Public Interest Legal Foundation, a law firm dedicated entirely to election integrity.

Escobar, a Democrat who is known for pushing back against political corruption, took on the “mail-in mafia” of ballot harvesters in Starr County and investigated and prosecuted fraud as it was happening. Adams, a Republican who served on President Trump’s election integrity commission, specializes in federal litigation to enforce the cleanup of corrupted voter rolls—including a pending case in Harris County.

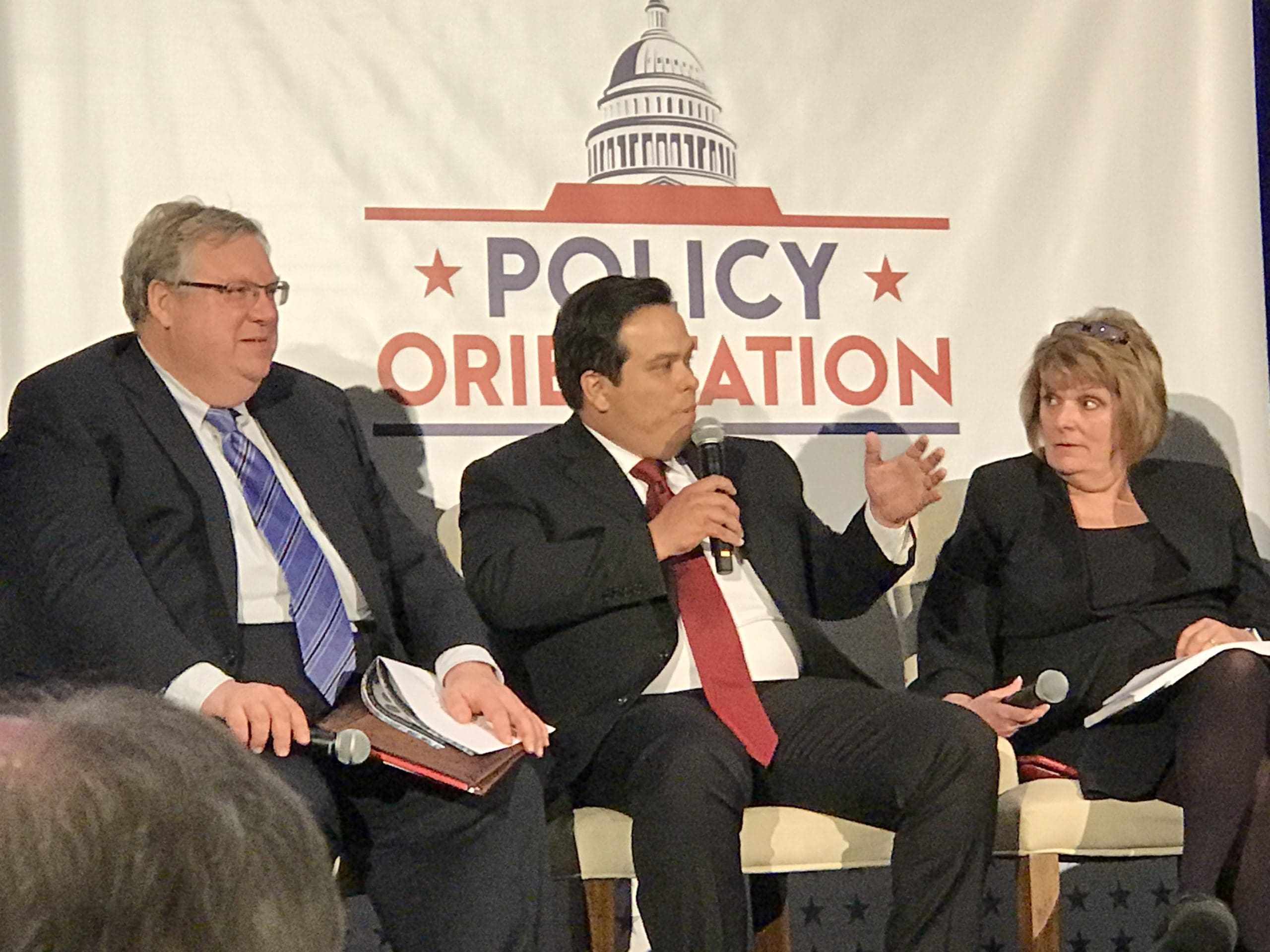

Both took part in a panel discussion of election integrity issues at the policy event, along with State Rep. Stephanie Klick (R–Fort Worth), chair of the Texas House Elections Committee.

“This is a very important topic for both Texas and the nation, and for our representative form of government,” said TPPF Vice President of National Initiatives Chuck DeVore, who moderated the panel.

Problems

Escobar targeted organized mail ballot fraud and illegal voter assistance at the polls as top election integrity issues Texas should tackle, adding that prosecutors need more investigative tools and resources.

The district attorney described how campaign workers called politiqueras profit from mail ballot harvesting, making money based on the number of votes they have “in the bag”—usually from elderly voters and often gained through coercion.

In 2018, his office caught Starr County politiqueras using a new tactic to steal votes: checking the “disabled” box on mail ballot applications of voters who aren’t disabled—something elections administrators have no way to verify. Rather than follow the usual policy of waiting until after the election to investigate, the district attorney used local resources to expose the fraud in real time and stop the illegal votes before they were counted.

“If we follow the guidelines and [are] not asking any questions, you’re left with probably a compromised election that you’re trying to investigate piecemeal years after the fraud happens,” he said. “It’s untenable. This system does not work.”

“Mail-in is only part of the problem,” Escobar added. “At some point, the ‘mail-in mafia’ will begin to diminish, and you’re going to start to see more of this other kind of fraud happen, where people are getting assisted who don’t need assistance, in the polling location.”

He also said prosecuting fraud cases is very hard to do without local resources and without the local will to do it. “Texas does not have the resources at all to handle election fraud,” he added:

Election fraud exists. It happens. And for anyone to say it is nonexistent and is somehow a myth that has been created by one side of the political spectrum should completely be debunked, because it exists. There should be no question at all.

And this idea [that] there’s not enough, we need to be working on other issues … how much election fraud does it take for us to be really paying attention? Is it when your side begins to lose elections that it starts mattering?

Adams, a former Justice Department Voting Section attorney, agreed with Escobar that mail ballots are a major problem, along with corrupted voter rolls that enable illegal voting.

“The biggest threats to the integrity of our elections are not voting machines,” he said. “They’re noncitizens getting on the rolls and voting, and they’re paper ballots in the form of absentee ballots being manipulated through intimidation.”

“We’ve seen it all over the country,” he said. “But a lot of it is going on in Texas.”

The other major challenge is the left’s organized opposition to election integrity measures.

“You cannot underestimate the amount of money opposing anything that is done,” Adams said. “The left has this huge network of funding, of litigation, of resources devoted to stopping any reform.”

“The left is going after Texas,” he added. “Any reforms you do are going to be attacked.”

Klick said lawmakers did address a few key issues this session. One of the most important election bills passed this legislative session, she said, was a requirement for electronic pollbook security standards. She said she also got funding for Texas to participate in a voter registration crosscheck program with other states—an initiative mandated by the legislature in 2015 but never fully implemented. “List maintenance is hugely important to avoid the risk of fraud,” Klick said.

She agreed with Escobar that illegal voter assistance is a problem, adding, “I’ve also seen election workers attempt to ‘assist’ a voter who doesn’t require assistance … control the device and make selections.”

Solutions

“It’s going to take some out-of-the-box thinking,” Escobar said.

“We have to figure out how to prevent voter fraud,” he added, “not try to use these laws afterwards, the threat of prosecution to somehow prevent it.” Because investigations don’t usually happen until well after the fraud occurs, the person elected by fraud has already been in office and making decisions that impact taxpayers for years before a case is resolved.

Escobar testified in favor of mail ballot and voter assistance reforms included in this session’s Senate Bill 9 and asked lawmakers to consider adding an enforcement provision that would allow authorities to proactively prevent fraud before it happens. But the big omnibus election integrity bill didn’t make it out of Klick’s committee in time to make it through Calendars and onto the House floor for a vote, stalled over pushback from the left over the proposed reforms and internal disagreements over voting machine provisions.

“There’s no easy fix,” said Adams. “The left has changed the culture about voter issues to such a degree that so many DA offices that get a complaint don’t want to go anywhere near it.”

Adams said Texas should keep pursuing strategies to verify voters’ citizenship status after they register, as federal courts have shut down efforts to require proof of citizenship in advance. He said huge mistakes were made in Texas, referring to the rocky rollout of a program to compare voter rolls to driver’s license data that drew federal lawsuits from leftist groups to stop the process. While the Secretary of State immediately recognized about 25,000 of the 95,000 voters first flagged as noncitizens had been naturalized, the state and counties were left to sort through the thousands of remaining flagged voters without communicating with them—the easiest way to clear up the confusion. “We have to get it right,” Adams said. “Every time we get it wrong, the left scores another victory here.”

“Here’s the good news,” he added. “There is no other state that devotes the resources to fighting voter fraud that Texas does.” The bad news: in places like Harris County, officials aren’t interested in improving election integrity. His firm is suing the county’s Democrat voter registrar to get noncitizen voter records, which are subject to public inspection under the National Voter Registration Act.

Adams told Texas Scorecard he hopes that the case is resolved before it costs taxpayers any more money. “We hope the case settles and the citizens of Texas can see how bad the problem was of foreigners voting in Harris County.”

He also warned against “absentee ballot creep”—expanded use of fraud-prone mail ballots. “The more elections [that] take place with an observer, an election official, the better,” he said.

Klick agreed that observation and citizen involvement are key. “It’s really important from a security perspective that you have people of both political parties inside the polling place,” she said. “That keeps people honest.”

Voters who observe illegal activity need to report it immediately to their local district attorney and the Texas Secretary of State’s office, she added. “Don’t wait.”

DeVore suggested candidates and parties who appoint poll watchers should have attorneys standing by to help resolve problems at the polls as they arise.

Citizen Engagement

Texans are ready to tackle the problem of election fraud and find effective solutions. But policy prescriptions alone are not enough to ensure honest elections.

New legislation won’t be considered until 2021 unless Gov. Greg Abbott calls a special session, something he’s shown no interest in doing despite calls from the grassroots. When lawmakers do reconvene, election integrity proponents must be on the same page about what policies to pursue.

Meanwhile, groups that benefit from lax rules—or who simply want to vilify their political opponents—will continue to fight in federal court against election security measures, claiming “voter suppression.” Policy makers can’t avoid the left’s attacks, but smart reforms can deflate them. Election integrity advocates can and should be in the fight too.

Yet even the most stringent voting rules can’t secure elections if corrupt or incompetent officials fail to follow them.

Election integrity ultimately depends on citizens engaging in every step of the process and holding their election officials accountable.

Correction: The original version of this article stated that Senate Bill 9 did not pass out of the House Elections Committee. This version has been corrected to reflect that the bill was passed out of the Elections Committee but was not scheduled for a floor vote by the House Calendars Committee.