Texans living in one of the fastest-growing areas in the nation delivered a message to lawmakers tasked with redrawing the state’s political maps next year: Don’t California our Texas.

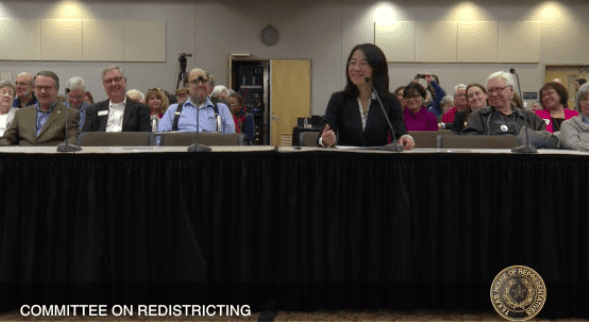

At a public hearing in Collin County last month, members of the Texas House Redistricting Committee heard local citizens’ suggestions and concerns about the decennial map-making process. Top among them was to keep the task in the hands of elected representatives who are accountable to the voters.

In Texas and most other states, elected lawmakers are responsible for redrawing voting district boundaries after every 10-year census. California is among a handful of states that have turned over redistricting power to “independent commissions” of unelected bureaucrats.

“I believe this process can only be successful if those accountable to the people are directly involved in those decisions,” County Commissioner Susan Fletcher told the panel.

“I’ve heard discussions about appointing unelected and unaccountable representatives to oversee this process. I want to express my emphatic disagreement with such an un-American idea. Why would we allow anyone other than those whom the people have elected to handle such an important matter?”

The move to commissions is being pushed by the left as a “fix” to make redistricting less political. In last year’s legislative session, Democrat State Rep. Rafael Anchia of Dallas proposed a constitutional amendment to change Texas to a California-style system.

At the Plano hearing, Democrat state House candidate Tom Adair was the lone speaker asking for an unelected commission to take over redistricting from legislators, “to get partisanship and politics out of the process.”

Yet research suggests the switch doesn’t result in less partisan gerrymandering, just less accountability.

“Texas is not California,” Fletcher added. “And I, for one, am thankful for that.”

She wasn’t alone. Over 30 residents of conservative Collin County spoke at the hearing held in Plano, and most agreed with Fletcher.

“California does have a lot to teach Texas about what not to do,” Janet Gagnon, a recent transplant from the Golden State, told the committee. “California has taken gerrymandering up to an art form, not just in the shapes of districts, but in their refusal to acknowledge different cultures within each community.”

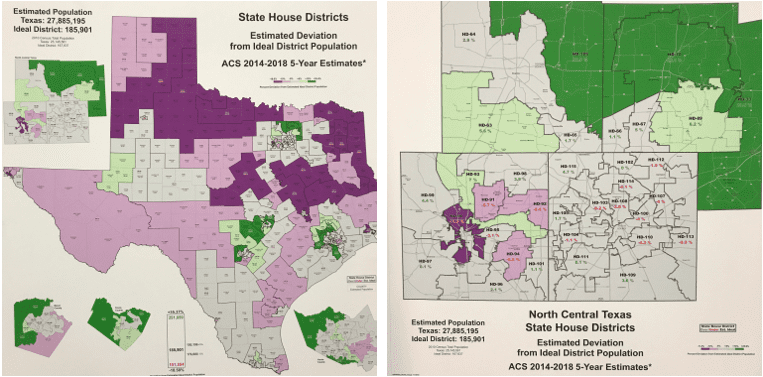

Mark Reid, chairman of the Collin County Republican Party, noted the county is expected to exceed 3 million residents in the next 20-25 years. The area’s explosive growth over the past 10 years—fueled in part by former Californians like Gagnon—means residents should gain representation when redistricting is completed in 2021.

“The current districts represent the existing voting patterns in Texas,” Reid said. “We ask that you respect those voting patterns and adjust the districts to maintain them.”

In Collin County, every partisan elected office is held by a Republican, and residents see a connection between policies and population.

“Without doubt, it is because of the prolonged economic success of this region that we are a rapidly growing community,” said U.S. Rep. Van Taylor, whose 3rd Congressional District includes most of Collin County.

County Judge Chris Hill agreed, crediting the “Texas Miracle” for the growth that’s requiring lawmakers to rebalance the population among districts in the area. “The task falls on your shoulders to draw these new lines,” Hill told the panel.

“Collin County deserves its own Senate district completely located in Collin County,” added Carroll Maxwell, a fixture in local politics for decades. With a part of Senate District 8 now in Dallas County, he said, someone could be elected to the seat that has no connection to Collin County.

“Communities of interest are very important,” said longtime political activist Mike Openshaw. Collin will be big enough for five House districts and a portion, he said, and that portion should go to adding rural voters to a rural district. Openshaw added “the No. 1 priority” in redistricting seems to be “incumbent protection,” followed by partisanship.

“We think communities of interest should focus on characteristics that unite us,” said Maggie Whitt, a GOP precinct chair and head of the Minority Engagement Group. Whitt spoke on behalf of 35 signers of a letter asking for fair representation, which she said means “no gerrymandering to pigeon-hole any special interest group.”

Along with accountability, citizens identified transparency as a top priority.

“Voters want to be able to hold you personally responsible for these districts,” said John Myers, a resident of Collin County for more than 30 years who also rejected using unelected bureaucrats to draw political boundaries. “I am watchful and diligent to make sure the districts in North Texas are appropriate and legally drawn,” he added.

“We appreciate the fact that you are allowing us to watch you, and we will be watching you throughout this whole process,” said Mike Giles, a grassroots conservative leader in McKinney.

Lily Bao, a first-generation immigrant and one of the first Asian-Americans elected to Plano City Council, explained why redistricting is so important to local residents.

“We are here because we love Texas,” Bao said. “We chose Collin County because it represents the American dream that we all come here to pursue.”

Bao said ethnicity is not what matters. Her family, and many in the Asian-American community that makes up 19 percent of Plano’s population, choose to live in Collin County because it offers opportunities to prosper economically and education-wise in safe, diverse neighborhoods:

“When you do your job … make sure it still keeps us what we have been. Keep us on the track of success. That’s why people move here. Don’t change it fundamentally. Don’t turn us into California.”

Actual map-making won’t begin until next year, after the state receives data from the 2020 census. Lawmakers will hold hearings and solicit public input throughout the process. Texans are encouraged to visit the state’s Texas Redistricting website and contact House and Senate redistricting committee members with questions and comments.