Across America, we continue to see so-called disease experts and their acolytes convincing politicians to restrain citizens’ desire to reopen. And so folks have not been allowed to return to their business, schools, and churches.

These actions are all based on a risk assessment of the Chinese coronavirus that’s proven not to be as devastating as many feared.

But while it’s certainly prudent to make projections on what might happen, how much stock should we put in those projections? And what are the limits on the actions that are appropriate based on projections alone? To answer that question, let’s look at a subject we project on a daily basis: the weather.

When I was a child, I remember my parents interrupting my favorite TV show (The Magic School Bus, for those wondering) on “the eights” to flip over to The Weather Channel and get the weather forecast for the next few days. With smartphones, that’s no longer necessary, but the product is still the same. A few taps, and you can see what weather experts predict will happen for the rest of the day anywhere in the world for up to the next two weeks.

Looking at the screen, we generally trust what’s predicted for the rest of the day to occur. But what about tomorrow? What about in 10 days? How many times has the 100 percent-predicted rain never arrived? Do we cancel plans a week in advance because there’s a predicted thunderstorm?

Of course not. We know meteorologists rely on models to predict weather events—models that have a large degree in the variance of what they predict. We know those models can’t possibly account for every single variable that contributes to our weather—and we adjust our expectations accordingly.

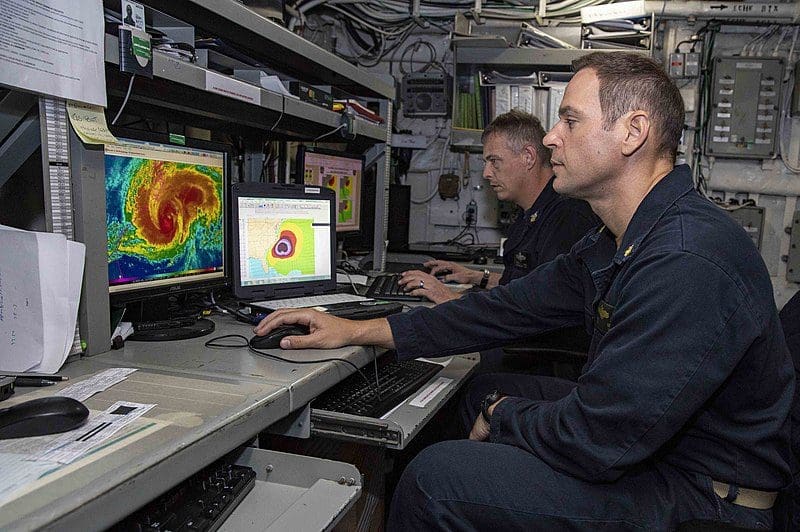

We see this on full display every hurricane season when small storms off the coast of North Africa spin themselves into deadly events that assail the American Gulf Coast. When they’re a week out, we often see a “cone of uncertainty” over a wide range of areas that could be impacted. Perhaps the storm could hit Corpus Christi? Perhaps it could hit Beaumont? Perhaps it could fizzle out and hit no place at all.

But when the storm is out east of the Bahamas, most people in Houston aren’t doing anything more than ensuring they are prepared to prepare. They might make sure they have enough toilet paper, bottled water, and flashlight batteries because they don’t want to fight the crowd in a couple of days, but they’re not filling sandbags in the front yard or evacuating their family to grandma’s house in Dallas.

Likewise, their kids’ school principal hasn’t sent them an email canceling classes, and their manager at work certainly hasn’t told them they don’t have to worry about coming in to work the next week. Their local governments might be blustering about preparedness, but they’re not issuing evacuation orders.

Nor should they be.

Every fall, school districts, employers, and families make the decision to hold off on incurring the economic and personal costs of disrupting their everyday lives until they are reasonably confident the situation demands it.

It’s expensive for employers to shut down parts of their businesses. It’s costly for local governments to activate overtime for first responders. And it’s a huge hassle for a family near Houston to pull down the boards from the attic and affix them to the windows, pack suitcases for children, and try to find the pump for the air mattress that always finds a way to get lost.

It’s particularly expensive when all that effort ends up being for nothing.

Thankfully we don’t treat hurricane projections like we do Chinese coronavirus projections. But what if we did?

On Thursday, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted an “above-normal” hurricane season with 13-19 named storms, 6-10 hurricanes, and 3-6 major hurricanes likely to form in the Atlantic Ocean according to their models.

After seeing the news, I contacted a few friends and family members who live along the coast to share the news with them and ask if they had made plans to evacuate yet. I even offered my guest room should they become hurricane refugees.

“What are you talking about? Why would I evacuate right now? You know those projections are never very accurate,” said one.

“You’re being ridiculous. I’m not leaving my house now because of what might happen in four months,” said another. “Then again, maybe [Harris County Judge] Lina Hidalgo will order that next!”

These are smart, savvy folks who have all evacuated for hurricanes before. Both of the people I quoted even have college degrees in scientific fields. Do they not believe in science? Do they not believe in hurricanes? Why do these people not trust the data and doctors (of meteorology)?

In truth, they do trust the data and doctors. They trust them to likely be wrong, to be constrained in how accurately they can predict the future. And they believe right now the projections alone of what might occur in four months don’t merit incurring the social and economic costs this far in advance.

Like all of us do every day, they’re engaging in a cost-benefit analysis in how they consider what is happening, what they know will happen, and what they believe might happen in the future.

The status quo with the Chinese coronavirus should be no different. It would be no different if people were allowed to make their own decisions—if politicians would think for themselves instead of relying on the projections of so-called experts.

To recap, here’s where we are:

It’s beyond dispute that we’ve put more time, effort, and energy into predicting meteorological events than epidemiological events. The fruit of that additional investment has yielded a product most people consider incapable of making reasonably accurate predictions 72 hours in advance. We all know this, and as a result, we don’t make major decisions based on mere projections until we’re confident they could come to pass.

Meanwhile, we have a Chinese coronavirus that is new. As the name COVID-19 implies, it’s less than a year old. Unlike hurricanes, we don’t have 100 years of data with which to make reasonably accurate predictions on what will happen. And unlike hurricanes which present intensely complicated thermodynamics problems, the spread of disease relies on systems a degree more complicated still.

The people who are most knowledgeable have tried to think up what might happen. And they’ve failed. Thus far, every projected doom-and-gloom scenario our “experts” have predicted will come to pass has not materialized.

There’s been a tragic loss of life, to be sure, but there hasn’t been anything close to the scenario many feared.

Our experts who understand very little have constructed woefully inadequate models they’re applying to an infinitely complicated problem and are producing projections that have thus far been nothing other than entirely wrong. Yet politicians are continuing to listen to their advice on delaying reopening, canceling events, and prohibiting people from going back to work.

Our leaders are accepting devastating and easily foreseeable costs in jobs, time, and treasure in order to stave off a future possibility that might happen. They are listening to fearful projections from doomsayers who have been proven wrong time and again.

Texans wouldn’t put up with this for a hurricane. Why should this scenario be any different?