On TV, a murder is solved within two commercial breaks. At the movies, a galaxy-spanning war can be resolved in under an hour. Even when we read real accounts of great movements, everything is neatly contained between two covers and around 500 pages.

Yet when visiting the great cathedrals of Europe, I have always been struck by the sheer number of years involved in building them – entire generations came and went in the work of creating a place of worshipful beauty. The work itself, spread over a millennia, is an act of worship.

It’s easy to forget that great things take time. And, often, that those who prepare the soil don’t get to reap the harvest.

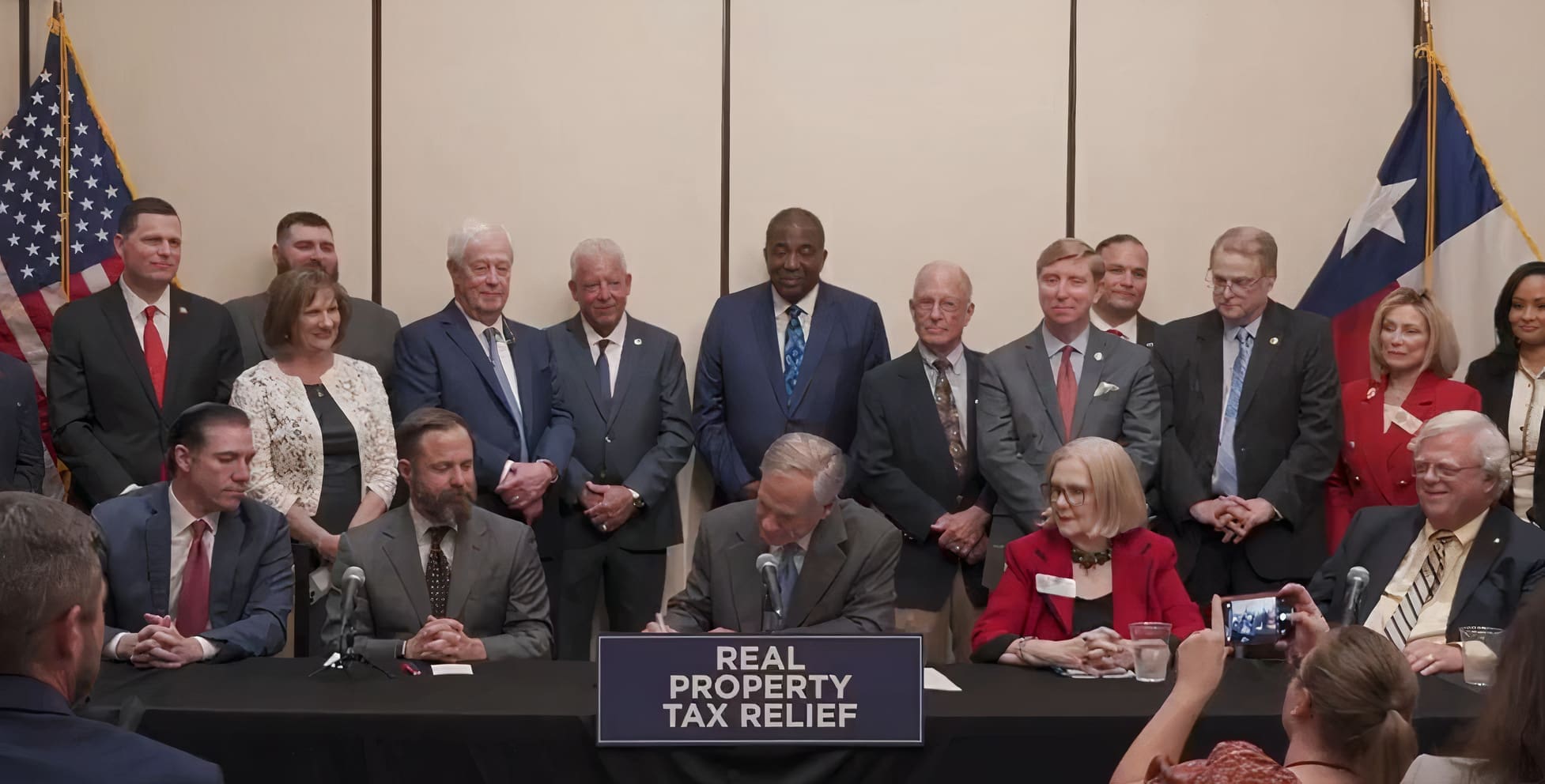

It has taken decades, but earlier this year – with almost no fanfare – the Texas Legislature finally passed a strict limitation on the growth of state government spending. This didn’t happen overnight.

In the 1970s, there was a move led by a former California governor named Ronald Reagan to limit the growth of government – to control the leviathan of the state by controlling its diet. Texas lawmakers, eager to capitalize on a national trend that wasn’t disco pants, did what Texas lawmakers almost always do: the absolute minimum. The spending limit enshrined in the Texas Constitution had the words without the substance, limiting nothing. In fact, lawmakers completely ignored what token limitation it provided for the next decade and a half.

That’s when a firebrand lawmaker named Talmadge Heflin, a Republican from Houston, took the state to court to enforce the application of the limit. As meaningless as the limit was, Heflin’s action put the tool on the radar of grassroots activists. Over the next twenty years, conservative activists made using, and then strengthening, the state’s spending limit a top priority.

Not only did conservative activists push the issue from the outside, but the Republican Party of Texas adopted it as a key plank in their fiscal policy platforms each biennium.

Legislative efforts driven by citizen activism toiled on, reaching fruition in 2021 when legislation putting a tight lid on future state spending was adopted. Of course, it doesn’t actually take effect until the 2024-2025 state budget that will be adopted in 2023

But the story of limiting government spending doesn’t actually end there.

Since the effort began in the 1970s, a nagging question has been what to do with the surplus money – that delta between what government gets in taxable revenue and how much of it they can spend. The easiest answer, giving the money back to the taxpayers, now has practical application.

The spending limit will generate massive surpluses, all of which can be used to reduce Texas’ massive property tax burden. The spending limit is a key component in a plan that would see public school property tax burdens eliminated a decade from now.

In fact, eliminating property taxes can only happen by reducing the growth of government. That’s because tax problems are symptoms of spending problems. Your taxes are burdensome only because government spends so much.

Many of the well-intentioned activists of the 1970s who pushed originally for a spending limit weren’t around to see it made whole, but their work cleared a path. Those who fought to make the weak limit strong have since retired or moved on, but they built a strong foundation. And those who were around for the limit to be made real won’t necessarily reap the benefits of its actual implementation.

In the great works of life, none of us are actually called to be successful – we are called, however, to be faithful. Part of that faithfulness is in working toward a greater goal that might not be completed in our lifetimes.

As activists, we must be committed to the long fight – to a willingness to fight for a better tomorrow we might not ourselves see. The cause of liberty is advanced not in giant leaps, but in persistent and consistent steps forward.

Pushing onward together we can build a culture of life and liberty more beautiful than any cathedral.