While Democrat city officials in Texas’ capital city are claiming to move past racist policies like segregation, they are creating a separate city services facility for citizens with brown or black skin color.

Earlier this month, the Democrat-run Austin City Council passed resolutions formally apologizing for the city government’s “active involvement in segregation and systemic discrimination,” while at the same time beginning discussions on how to spend more tax dollars based on skin color and making plans to construct a “Black Embassy” downtown.

The station, which will offer resources and support but be separate from the main city hall, will only service based on skin color.

“The City desires to create a centralized Black resource and cultural center – a Black Embassy – that is geared to the success and cultural promotion of the demographics in need by providing relevant resources, and support for existing and future black-led businesses and organizations,” read the council’s document.

The council also directed the city manager to study and come up with a modern-day price tag of the city’s past racist policies, and “call[ed] on Travis County, local school districts, the State of Texas and the federal government to initiate policymaking and provide funding” for what they deemed “reconciliation.”

However, according to Nook Turner of the Black Austin Coalition, those taxpayer dollars will be used to start the segregated embassy.

“It’s going to offer resources. It’s going to offer finances. It’s going to offer A to Z for Black people’s need to rebuild a district and to be able to have sustainable life and to be able [to] enjoy a high quality life,” said Turner.

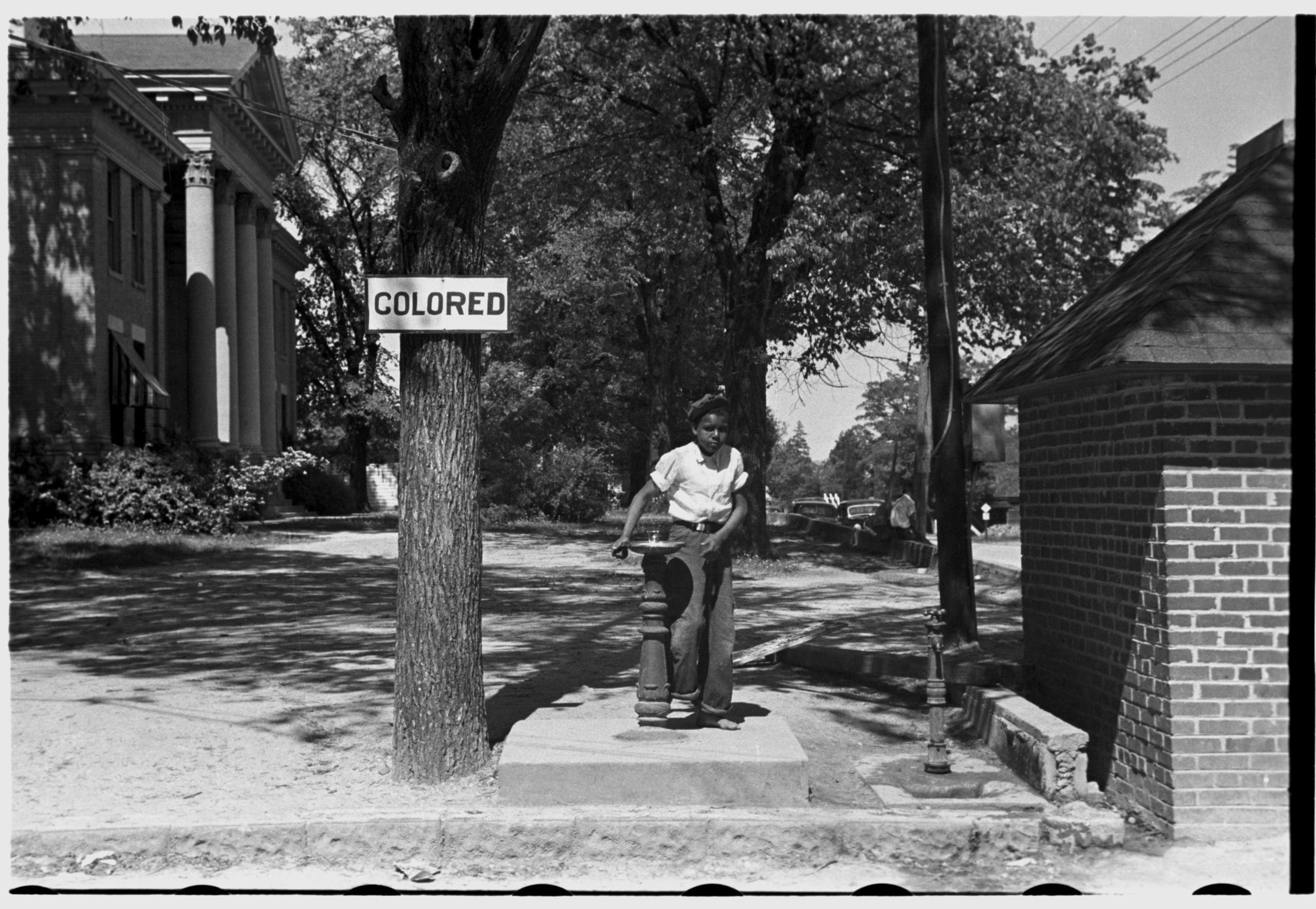

Ironically, in one of the council’s March resolutions, they rightly condemn past “separate but equal” segregation such as Austin’s 1928 city plan, a downtown development strategy that “separated Austinites with race as a sole factor.”

The 1928 city plan contained a legal workaround strategy to divide black Americans into a “Negro district,” by encouraging them to move to the east side of the city.

“It is our recommendation that the nearest approach to the solution of the race segregation problem will be the recommendation of this district as a negro district; and that all the facilities and conveniences be provided the negroes in this district, as an incentive to draw the negro population to this area,” the 1928 plan reads, adding, “We further recommend that the negro schools in this area be provided with ample and adequate play ground space and facilities similar to the white schools of the city.”

“Parks were built for African Americans, and parks for whites and Latino schools were placed in very specific parts of the city,” wrote Andrew Busch, a visiting assistant professor at Miami University who wrote his dissertation on the history of segregation in Austin.

“What the plan basically said is that in order to get city services you would have to move east of East Avenue, which is now our I-35,” said former Austin Councilmember Ora Houston.

Apparently, the present-day city council is following in the footsteps of the 1928 plan, creating separate facilities for people with different skin colors. The council’s new “Black Embassy” will be located in East Austin.

Ironically, at the early March council meeting when they voted to begin the new segregated facility, Council Member Sabino “Pio” Renteria recalled his childhood in East Austin, where he “lived through this episode of seeing ‘colors only’ and ‘whites only’ signs at the Greyhound, going to Woolworth’s and seeing the counter separating people.” Renteria added, “There’s been a lot of injustice.”

“To separate [children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone,” wrote U.S. Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren in the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case, which desegregated public schools and, by implication, all public facilities.

“Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” said Warren.

Texas Scorecard reached out to all 10 council members and Mayor Steve Adler, asking for more information and clarification of whether the facility will indeed only service citizens of certain skin colors. What would happen, for instance, if an Austinite with white or tan skin went to the facility for help?

Neither the mayor nor any city council member responded to our request.

Citizens also reacted to the council’s “Black Embassy.”

“Is preferential treatment based on skin color still racist?” tweeted one individual, adding, “I feel like we need a Hispanic, Asian, Indian, Transgender, LGBTQ+, and White embassy #unite.”

Justice John Marshall Harlan, who wrote the dissenting opinion in the infamous 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case, said providing “separate but equal” services never led to a more unified and just society. The 1896 case was a dispute over the Separate Car Act that allowed officials to separate public facilities solely based on skin color.

“The thing to accomplish was, under the guise of giving equal accommodations for whites and blacks, to compel the latter to keep to themselves while traveling in railroad passenger coaches,” Harlan wrote.

“If a white man and a black man choose to occupy the same public conveyance on a public highway, it is their right to do so, and no government, proceeding alone on grounds of race, can prevent it without infringing the personal liberty of each.”

Concerned citizens may contact the Austin City Council.