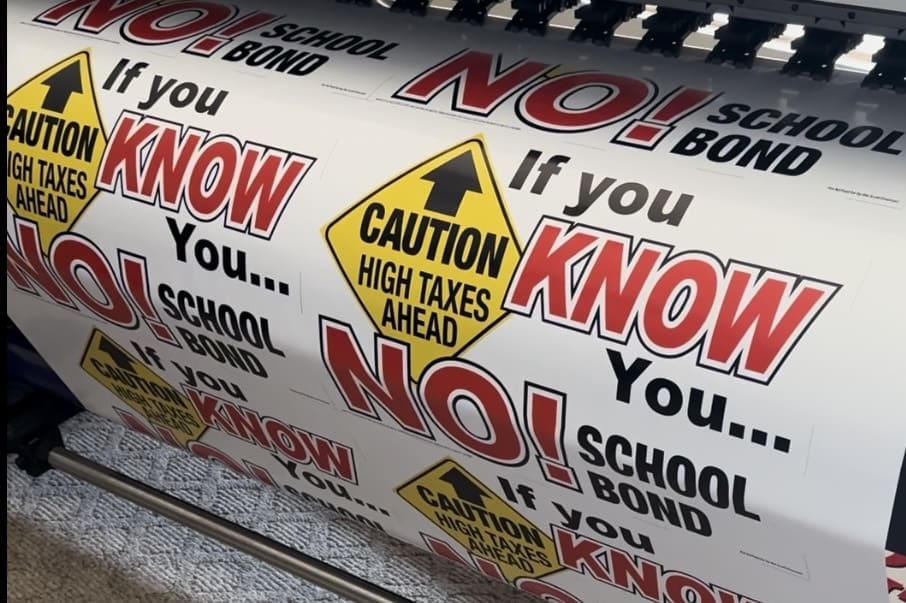

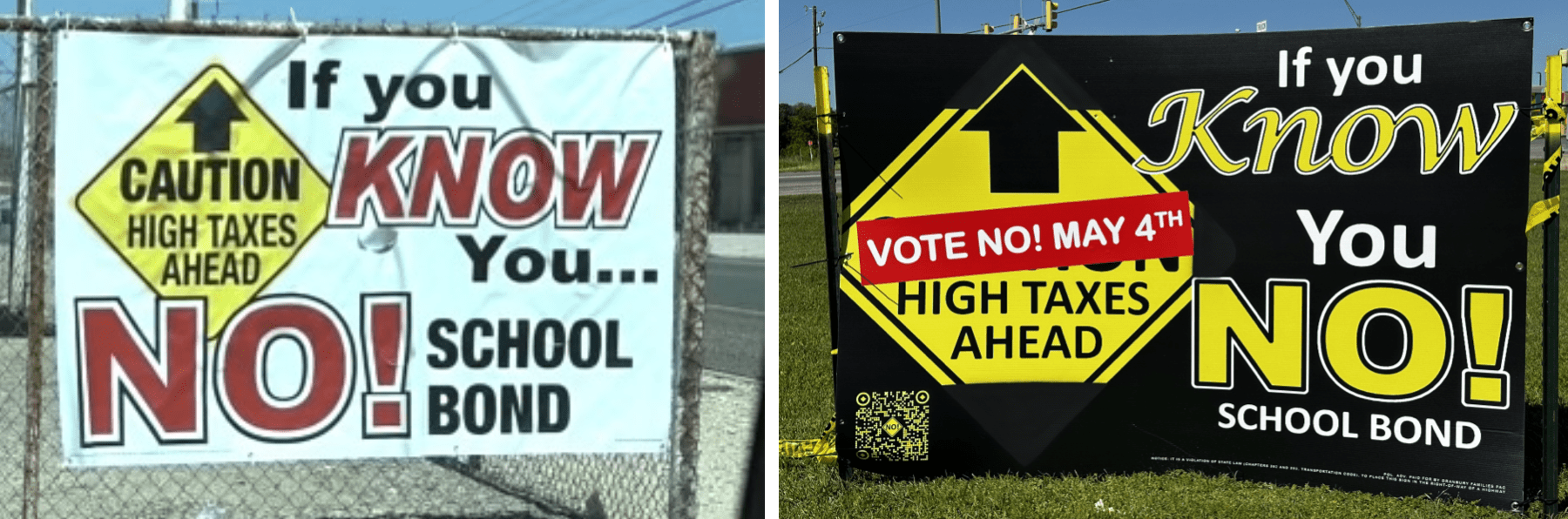

Residents of Big Spring who are opposing a big school bond on the May 4 ballot have taken inspiration from a voter education campaign in another Texas school district, copying the taglines “Caution High Taxes Ahead” and “If You Know, You No.”

Lifelong resident and business owner Scott Emerson organized the campaign against Big Spring Independent School District’s nearly quarter-billion-dollar bond package.

Emerson told Texas Scorecard a friend posted pictures online of a “Vote No” campaign in Granbury ISD cautioning voters about the property tax impact of their local school bond.

He decided to copy their catchy slogans for his effort.

“I’m very glad Granbury is not upset we mimicked their campaign,” said Emerson. “They were flattered.”

In addition to signage and slogans, Emerson created a series of short videos highlighting concerns about Big Spring ISD’s bond propositions, which he posted on his Facebook page and YouTube channel.

The cost to local property taxpayers is a top concern.

All school bond debt is repaid with property taxes.

The two bond propositions approved by Big Spring ISD trustees total $219 million, most of which would be spent on a new high school to replace the existing structure. But with interest, the bonds would cost local property taxpayers $430 million—almost double the dollar amount shown on the ballot.

Big Spring ISD officials acknowledge their proposed bonds would increase residents’ property tax rate by about 32 cents per $100 of taxable value. Even with the new $100,000 homestead exemption, the average homeowner would see a tax increase of $180.

Emerson is a longtime advocate of property tax reform and has served on the board of directors of the Howard County Appraisal District since 2020 as “the loudest voice against property tax.”

He said several other local business owners are also concerned about the property tax impact of the school bonds but are wary of coming out against them because many of their customers are school employees.

Big Spring ISD is the second-largest employer in the city, with about 600 employees.

District taxpayers already owe $53 million in bond debt principal and interest.

The added tax burden with interest—not mentioned in the district’s bond marketing materials—is just one reason Emerson adopted Granbury’s slogan “If You Know, You No.”

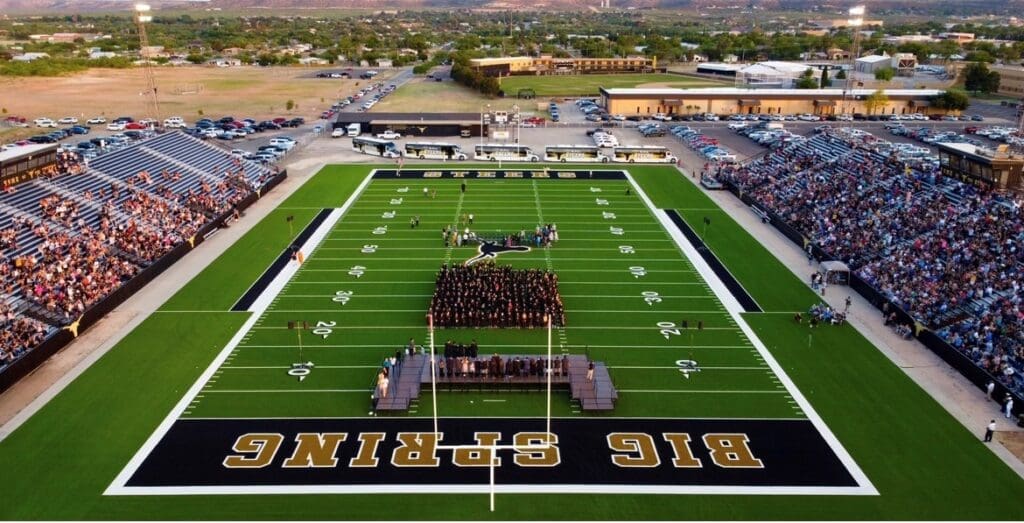

Big Spring’s proposed new high school, estimated to cost taxpayers $182 million plus interest, is another big bone of contention.

“The district has a horrendous history with school buildings,” said Emerson.

He explained that the district built a junior high school over a ravine.

“Citizens warned the district the school would sink. They’ve spent millions trying to pump it up, but it’s still sinking,” he said. “The plan for the new high school is on the same ravine.”

The planned school site also overlaps athletic facilities that the district recently spent tax dollars resurfacing.

“When the high school was built, there was a very good reason that they didn’t build on the ravine east of the gym. Years later, Superintendent Blankenship diverted this water so the field named after him could be built,” Emerson posted on social media along with a video of rainwater runoff. “It was not designed for a three-story building to be built on top of it.”

Emerson and others want more details on the proposed new high school and cost comparisons to refurbish the current facility.

He also said several elementary schools were poorly constructed, causing drainage problems. The district settled with the contractors for $1 million but included additional costs of fixing the schools in the bond.

“Where is that money? Why didn’t the district use it to fix problems before asking for bond money?” he asked.

Logan Churchwell, a Big Spring native who attended BSISD schools, recalls the construction fiascos when he was a student but told Texas Scorecard buildings and grounds are the least of the district’s problems.

The district has a history of failing to educate its students.

“My junior and senior years of high school, we were not issued textbooks because the district said they could not afford to replace them,” Churchwell said.

In 2015, the district was placed on academic probation for failing to meet educational accountability standards.

In 2021-22, the most recent year that Texas school district ratings were published, Big Spring ISD received a “C” overall and a failing 65 out of 100 for student academic achievement.

In 2022-23, only 36 percent of students met or exceeded grade level across all subjects.

Three-quarters of Big Spring ISD students are designated as economically disadvantaged.

“The school bonds and rebuilds are the biggest swindle in one of the poorest cities in Texas,” Churchwell added.

Emerson lays part of the blame on bond consultants, whose job is to sell the district on the highest-dollar plans possible because they earn a percentage of the total.

He said several school districts between Big Spring and Granbury floated bonds recently.

“It’s like they just work down the interstate,” he said.

He speculates that Big Spring ISD officials rushed their big bond package to voters without gathering complete information because other local taxing entities are also planning to hit residents with new property taxes.

Emerson believes the bond election results will be close, but he’s encouraged by the higher-than-usual voter turnout.

“Early voting numbers are breaking records,” he said.

As of Friday, the Howard County Elections office reported that 1,122 ballots had been cast in races countywide. The school district has 12,449 registered voters.

The high turnout may be due in part to district officials’ electioneering.

A district administrator sent an email to employees on April 20 announcing “early voting incentives” for staff members. The contest awards “jeans days” to campuses with the highest percentage of staff voting in the bond election.

Presumably, the district’s bond consultant is tracking school employees’ voting histories—a common practice used to boost turnout during bond campaigns.

The email also urged staff to “be an advocate for our kids.”

Emerson notes that such “motivational slogans” and “calls to action” are specifically prohibited and could constitute a Class A misdemeanor.

“No matter how much factual information about the purposes of a bond election is in a communication, any amount of advocacy is impermissible,” according to the Texas Ethics Commission.

Still, Emerson is optimistic that Big Spring voters will reject this bond, forcing the district to come back with a better proposal.

“So far, so good,” he said.

Early voting runs through April 30. Election Day is Saturday, May 4.