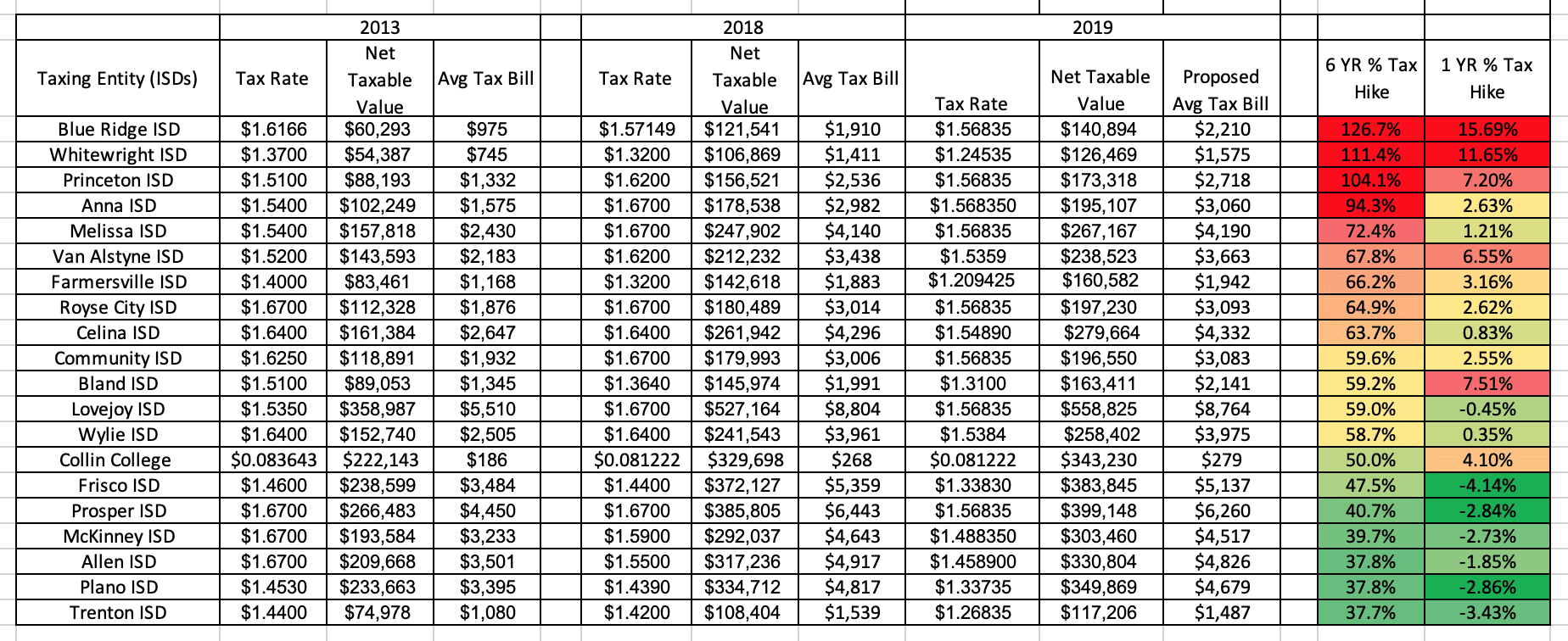

Average homeowners’ 2019 property tax bills from 13 school districts in Collin County grew, even though Texas lawmakers passed reforms last year that allotted roughly half of the state’s surplus tax revenue to reducing school property taxes. School districts—which have not had in-person classes since mid-March—are now setting their budgets and tax rates for the upcoming school year.

For years, homeowners’ property tax bills across the state have continued to grow, and roughly 60 percent of a homeowner’s total property tax bill is from school districts. In 2019, the Texas Legislature passed House Bill 3, which poured $5.1 billion of the over $10 billion tax revenue surplus into lowering independent school district (ISD) tax rates—but it wasn’t enough of a reform to stop the average Collin County homeowner’s bill from growing.

Lawmakers claimed HB 3 “lowers school property tax rates by an average of 8 cents in 2020 and 13 cents in 2021,” or an implied total of 21 cents over two years.

However, according to the Texas Education Agency, lawmakers’ claims were inaccurate. First, the average estimated school tax rate “compression” (or reduction) of 8 cents per $100 of property valuation will affect property taxes paid in the 2019 tax year, not in 2020. Second, there is no additional “13 cent” tax rate compression as the result of a state buydown in 2020.

Only seven of 20 districts in Collin County showed a one-year decrease in 2019.

Blue Ridge ISD board members approved the highest one-year growth at over 15 percent—from $1,910 to $2,210. This growth happened even though they slightly lowered their tax rate; year-to-year comparisons of tax rates are meaningless, as the average taxable value of properties fluctuates every year. In short, Blue Ridge ISD’s board members didn’t lower the rate enough to offset the over 15 percent increase in the average taxable value of single-family homes last year. The result was that average tax bills went up because they didn’t cut the rate deep enough.

But all school board members are aware that they can adopt a tax rate that would offset property value increases in the aggregate, keeping homeowners’ property tax bills, on average, steady from the previous year.

It’s called the no-new-revenue tax rate, and most school districts don’t adopt it.

However, Frisco ISD’s tax rate last year actually lowered average tax bills in the Collin County portion of the district—$5,359 to $5,137—and Trenton ISD had a decrease of 3.43 percent—$1,539 to $1,487.

But overall since 2013, all ISD boards increased their district’s average property tax bills for homeowners by no less than 37 percent. Blue Ridge ISD had the highest six-year growth of over 126 percent—$975 to $2,210. Trenton ISD had the lowest increase at over 37.7 percent—$1,080 to $1,487.

The Texas Education Agency confirms there will be a tax rate cut in 2020, the amount of which will vary from district to district, but says it will be provided via a different mechanism: a yearly 2.5 percent limit on growing property tax revenue. Regardless of what appraisal assumptions are used, this change cannot mathematically result in a tax rate cut of 13 additional cents, as state lawmakers claimed.

Unlike last year’s property tax reform for most cities and counties, school districts cannot go above the 2.5 percent limit whatsoever, but they can choose to not hike tax revenues at all. They could even choose to decrease them.

School boards are setting their tax rates as over 2 million Texans lost their jobs in 2020 due to government policies that shut down the Texas economy in response to the Chinese coronavirus.

Below is the data tracking the changes in average homeowners’ property tax bill from school districts in Collin County. Concerned taxpayers may contact their elected school board members.