In a sudden about-face, a school district in North Texas changed its quarantine policy regarding students it designated as having “close contact” with a COVID-19 positive student.

Frisco Independent School District announced their policy change on October 13, saying students who come in close contact with an infected student will not have to quarantine for 14 days—as dictated by the previous policy—if both students were wearing a mask at the time of contact.

The amendment came after an extended campaign by a concerned parent threatened to expose the school board for failing to comply with expert recommendations from the Texas Education Association (TEA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

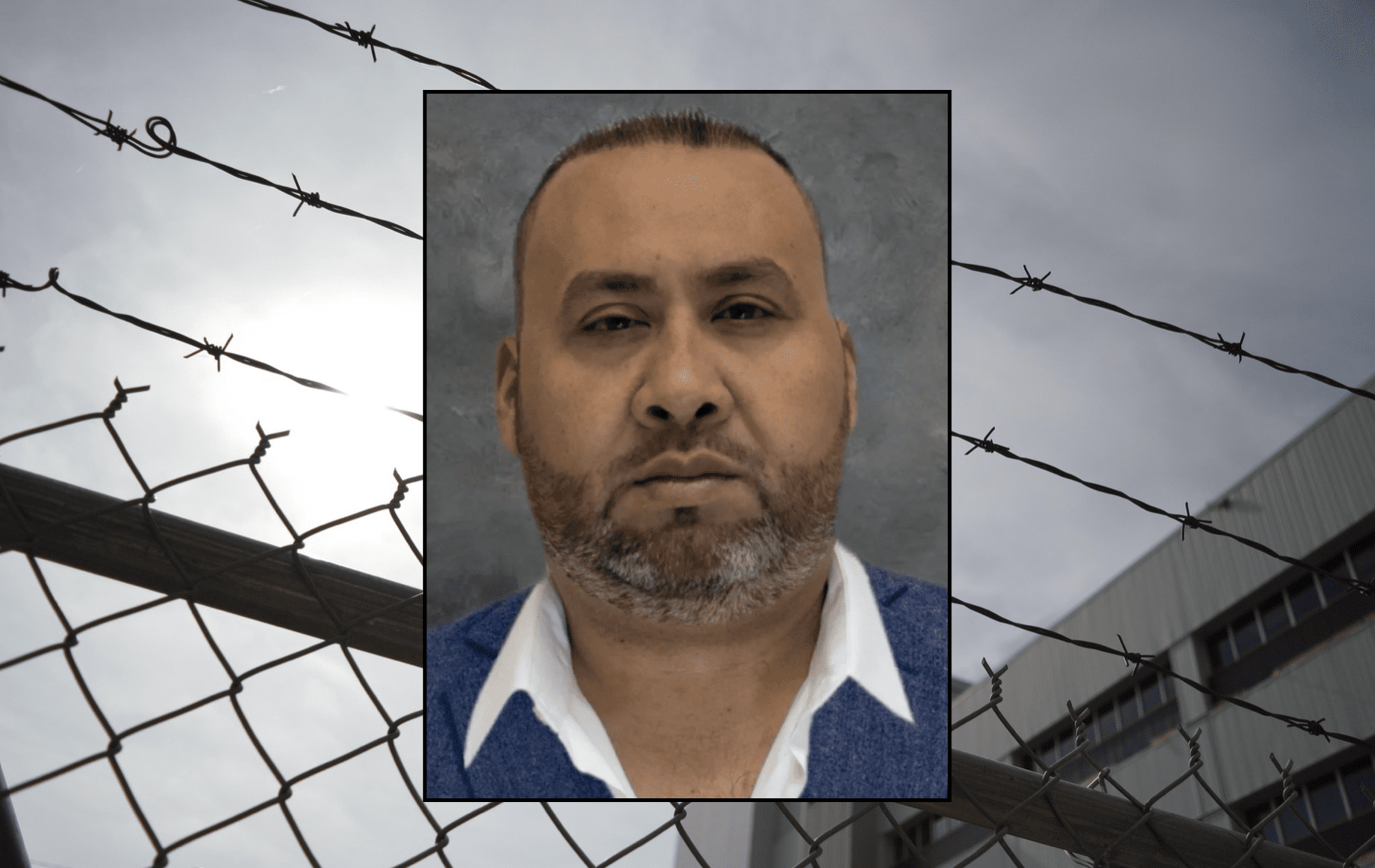

Parent Blayne Rush agitated for the change after learning high schools in the district were sending home kids without adhering to the suggested protocols established by the CDC and TEA.

“I believe in following science and the recommendations of experts,” said Rush. “And the ISD wasn’t doing that. It was just designating kids as ‘close contacts’ without weighing all the evidence, which the CDC says you should do. And by doing that, they were penalizing kids who had signed up to attend school by forcing them to go home when they weren’t really a risk.”

Both the CDC and TEA recommended weighing “mitigating circumstances” before requiring quarantine measures for anyone deemed a close contact.

But there was no wiggle room regarding close contact determinations at FISD schools, according to the district’s rules put in place when schools opened, as shown on their website:

Close contact is defined as within 6 feet of an individual with a confirmed case of COVID-19 for a cumulative 15 minutes or more during the time the individual remains infectious (“infectious period”) OR being directly exposed to infectious secretions (e.g., being coughed or sneezed on).

That definition made no mention of a clause on the TEA website:

Additional factors like case/contact masking (i.e., both the infectious individual and the potential close contact have been consistently and properly masked), ventilation, presence of dividers, and case symptomology may affect this determination.

The FISD ignored that protocol for weeks, requiring students to quarantine for 14 days if administrators determined a student had been within 6 feet of an infected person and spent a cumulative 15 minutes with that person.

Although the ISD does not publicly identify students who test positive for COVID-19 or those designated “close contacts,” their identities often become an open secret in tight-knit school communities.

“I heard about kids who the schools identified as close contacts and forced to quarantine when it wasn’t warranted. These students had been wearing masks the entire time and had barely spent any time close to an infected student,” said Rush, noting that “there’s a big difference between being near an infected person for 15 minutes in a row versus 2 minutes a day for five days.”

Rush wrote to the FISD superintendent and other board members to raise the fact that the FISD protocols failed to consider “mitigating factors,” but his concerns were dismissed.

“We will continue to use the current disease mitigation protocols that we’ve developed with local health authorities,” Superintendent Michael Waldrip responded in a September 22 email.

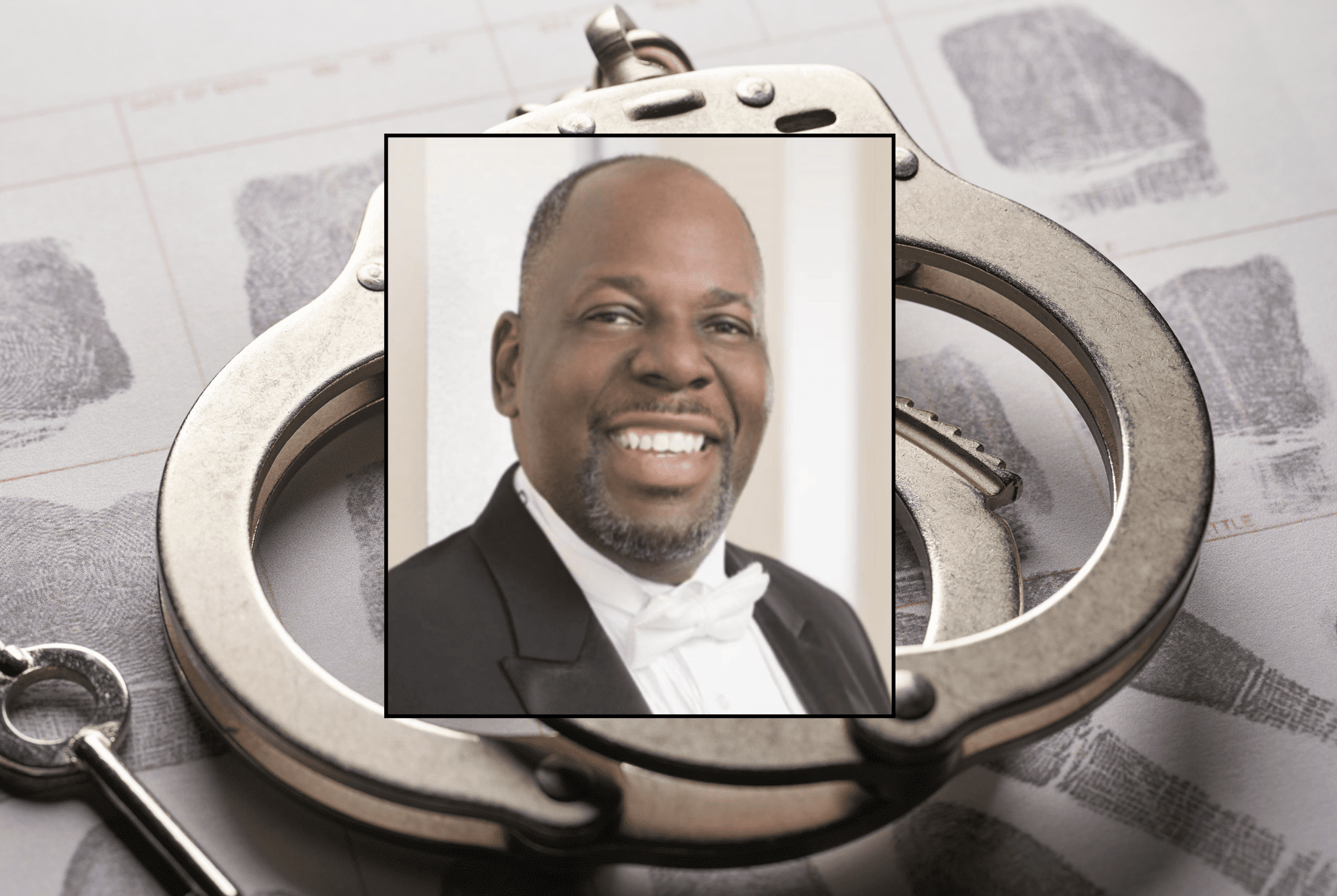

One week earlier, at a Frisco ISD Board of Trustees meeting on September 14, Daniel Stockton, the district executive director of government and legal affairs, laid out the district’s close contact policies with a statement that seemed designed to deflect criticism onto the TEA.

“The Texas Education Agency’s definition has changed, I think, four or five times in the past month,” Stockton said. “We’ve tried to stay as consistent as possible while making sure we’re following the guidance of the TEA.”

Rush said these comments felt like the entire school community was being gaslit by the FISD.

“I couldn’t believe these responses. They were obviously not based in the facts,” he said. “Anyone who can read could see the protocol differences between the FISD, the TEA, and the CDC.”

Meanwhile, Rush learned other disturbing facts: close contact students who were quarantining could not attend the Virtual Academy classes offered by FISD schools.

Instead, they had to self-school.

“These offerings are not on equal footing,” said one mother of a Frisco High student who was told to quarantine and never developed symptoms. “That’s my biggest issue with what they’ve done. You have the kids in the virtual academy, and then you have the kids in face-to-face, and the rules are not the same.”

According to the parent, who requested anonymity because she didn’t want her child penalized, “In some of the classes, they let the students use notes. In other classes, they don’t let the kids use notes.”

The parent said these discrepancies could impact grade point averages and class rank, which could hurt kids applying to schools in the Texas University System.

“My kid is very responsible and focused. But not every kid is. The situation is unfortunate and unequal.”

Another parent of a quarantining student who also developed no symptoms said her teenager—who never tested positive for COVID-19—had struggled to maintain his studies, and his grades had suffered.

“These students have to get their assignments from Canvas,” referring to the online portal used throughout the school year to post work and reading materials. “But they have to arrange tutoring and communicate with their teachers via email or schedule Zoom calls. They are at a huge disadvantage.”

After hearing these concerns—and learning the quarantined kids had worn masks at all times—Rush decided to push harder. He alerted Sheacy Thompson at the office of State Sen. Angela Paxton (R–McKinney) about the faulty close contact definition, and she approached the ISD, which continued to insist its protocols matched the TEA.

Then Rush decided he would have to expose the FISD publicly. He used his own money to hire a journalist to report on these issues.

The reporter interviewed several parents, studied email exchanges, and read various close contact guidelines. He then sent a list of questions to the FISD and the TEA asking about TEA and FISD close contact definition discrepancies.

The reporter also informed the FISD that these articles would be published by a well-known website devoted to Texas politics and governance.

Just over a week later, the FISD’s Stockton appeared at the district board meeting and announced a major change to the close contact definition—a change that should drastically reduce the number of students forced to quarantine.

“The primary change with this update, the primary difference, is that beginning [October 14], we will no longer quarantine individuals who were within 6 feet for 15 minutes if both the infected individual and the contact were properly wearing appropriate face coverings,” Stockton said.

“They caved,” Rush said with a combination of satisfaction and annoyance in his voice. “They saw they were about to be exposed for not being forthright.”

Rush said he was very pleased with the change. “Making kids stay home for two weeks and struggle to keep up with the work on their own was really unfair. If your grades suffer for it and you are a high school senior, it can really impact your college choices.”

But the real lesson for him is that constituents can force change, “but only if they hold their leaders accountable.”

“Without the pressure, there would not have been any change,” he said. “They never said that they would review their position until the TEA, senator, and journalist got involved. It is sad that it cost money to hire a reporter, but when the school board has immunity and that much power over the direction of our kids, sometimes it takes guerrilla tactics in order to force change.”

“Right is right, and you have to be willing to fight for what is right,” Rush continued. “Most parents do not understand what is going on, so the ones who do need to fight for those who do not.“

This is a commentary republished with the author’s permission. If you wish to submit a commentary to Texas Scorecard, please submit your article to submission@texasscorecard.com.