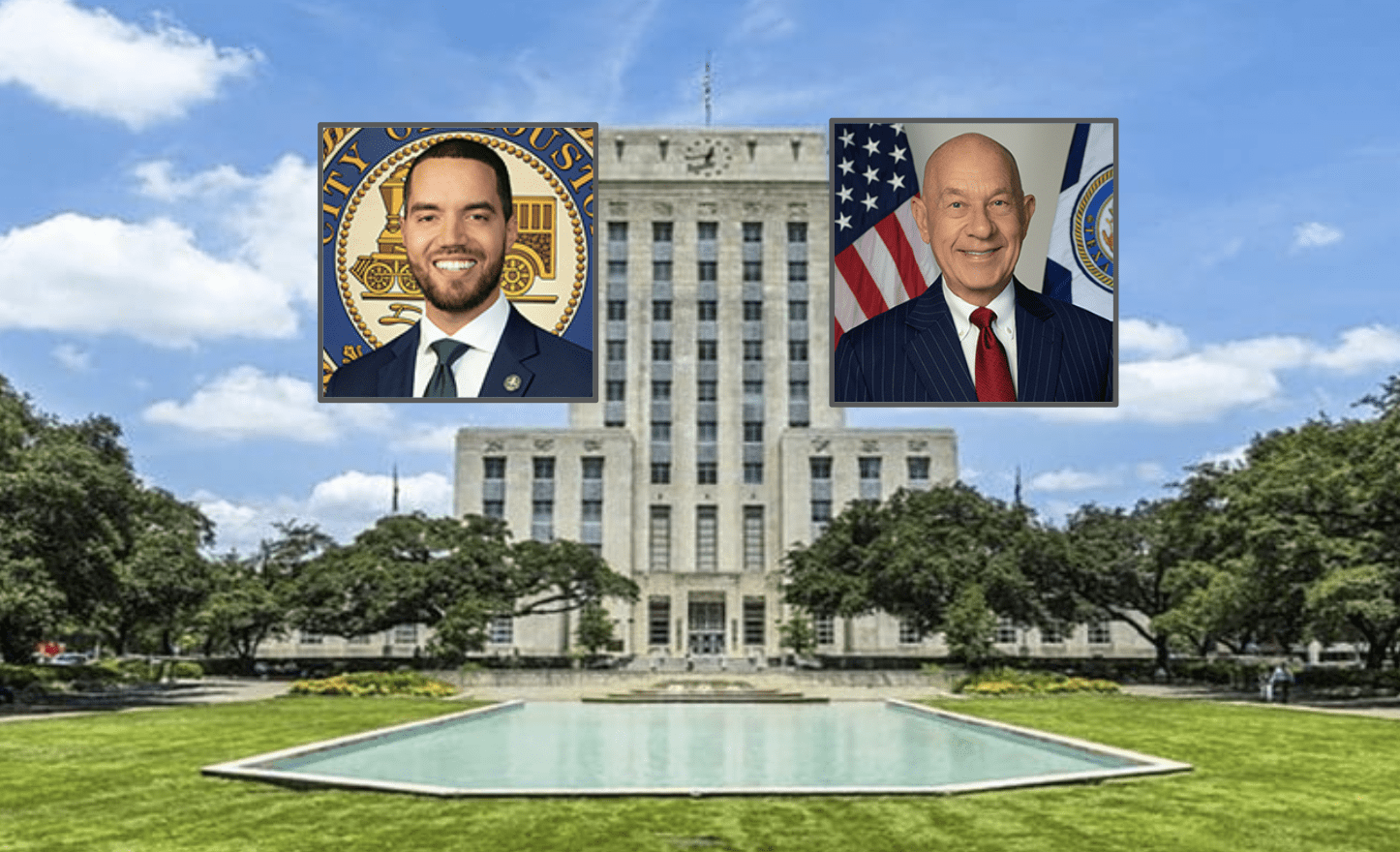

Houston taxpayers have had protection against increasing property taxes for almost fifteen years, but if Mayor Sylvester Turner has his way, that won’t be the case for much longer.

During the 2014 mayoral campaign, in the midst of pension talks, and as recently as his State of the City address, Turner has not minced words when it comes to his intention to bring a ballot item to voters asking them to repeal Houston’s property tax cap.

The cap was implemented in 2004 after a citizen-led petition drive placed it on the ballot. While both a property tax cap and a revenue cap were passed, only the property tax cap took effect and has since been implemented. Leading up to the possible campaign to repeal a significant taxpayer safeguard, it’s worth clarifying a few common misconceptions about that cap.

It’s a “Revenue” Cap

A subtle sleight of hand that proponents of the property tax cap repeal make when describing it is to call it a “revenue” cap. In reality, the cap only limits 25 percent of revenue coming into the city – from property taxes; the 75 percent of tax revenue from other streams is allowed to flow unimpeded. Tax revenue from the city’s tax increment reinvestment zones (TIRZs) is exempt from the tax cap.

The cap strictly limits the amount of ad valorem, or property tax, that the city can bring in during a given year. That number is determined by the actual revenue of the preceding fiscal year plus 4.5 percent, or revenues plus the combined rate of population growth and inflation, whichever is less.

It Ties the City’s Hands/Does Not Allow for Growth

Another argument often heard against the cap is that the city cannot manage increases in city services to accommodate for population growth with their hands tied by the cap.

As previously noted, the cap only limits 25 percent of revenues, while the rest can continue to grow. But the cap doesn’t stop revenue growth, it only limits it. This is an incredibly important distinction.

By tying the property tax cap to inflation and population, voters ensured that as more taxpayers move into the city, more property tax revenue can be collected. The cap is a floating cap rather than a stationary one.

While it doesn’t tie the city’s hands, what it does do is force prioritization.

The cap is meant to force city leaders, knowing the limitations of property tax revenue collections, to prioritize spending on what is most important. Unfortunately, that hasn’t always happened, so the city’s failure to prioritize has become the taxpayers’ problem to bear.

A Repeal Doesn’t Mean a Tax Increase

A recent op-ed notes that “since the charter amendment was enacted, the city’s property tax receipts have increased by 70 percent.” The city has consistently, even when hitting the cap, collected more revenue than in the past.

If not for a tax increase, then why repeal the only barrier between taxpayers and a cash-strapped municipal government? There is no reasonable answer other than that a repeal of the property tax cap will directly result in increased tax rates.

Taxpayers don’t often have a say in many of the spending measures that come from city hall, but if Turner’s plan advances as expected, they will have a say when it comes to restraining property taxes for current and future taxpayers in the city.

With school district property taxes uncapped, year over year appraisal growth, and a myriad of fees and levies imposed by the City of Houston and ancillary entities within it, the last thing taxpayers need to do is remove the barrier between them and the tax-hungry politicians in the fourth largest city in America.