Perhaps the most widely misunderstood concept in municipal governance is judging the size of the “property tax base.” When determining the appropriate tax rate, officials often err by considering only the median home values they tax instead of the total tax base, which includes commercial and other business property.

As a result, “median home values” and “tax base” are mistakenly used synonymously. For example, communities with relatively high median home values are mistakenly referred to as having a large tax base, or “property rich,” while cities with relatively lower median home values are perceived as having a small one, or “property poor.” Although home values are a significant variable in calculating the total tax base, using such an analysis is flawed.

The “median home value” metric fails to account for commercial real estate and business-personal property that are also taxed. In some cities, commercial property makes up half (or more) of their total tax base.

Additionally, property taxes aren’t a city’s only source of revenue. The second largest single revenue source, for example, is usually the sales tax, followed by a myriad of other fees. In some cases, property and sales taxes are levied to pay for related services.

As a result, cities that benefit from substantial commercial economic development and appraisal increases often fail to adequately lower their nominal tax rates to adjust for growth in the tax base. In other words, as the total tax base broadens and appreciates in value, a city may lower its nominal tax rate while simultaneously increasing its effective tax burden, or the amount taken out of the local economy.

In other instances, a city may lower both their tax rate enough to also lower their effective tax burden, while still collecting more in revenue than what’s needed for existing services. They then look for new pet projects to spend the money on as opposed to returning it to taxpayers. Some cities do compensate for an increase in revenue, in part, by dedicating sales and other tax revenue towards the lowering of property taxes or other fees.

But in order to have a meaningful discussion on the appropriate level of taxation, elected officials and taxpayers must first consider the size of their city’s total tax base—not median home values— after adjusting for population.

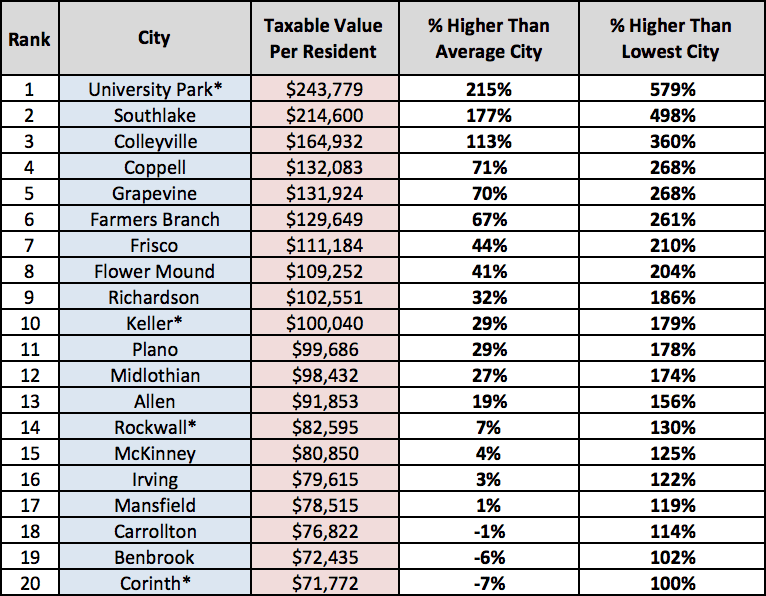

Below are the Top 20 cities in the Metroplex with the largest total property tax bases in 2014 on a per resident basis, net of any tax exemptions.

Across North Texas’ fifty largest cities, the average total taxable value per resident was $77,500. University Park, which consists primarily of residential homes of extraordinarily high values, has a total tax base over three times larger than the average city, and one nearly seven times larger than the lowest five cities—Duncanville, Watauga, Mesquite, Lancaster and Haltom City (not listed above).

But other communities with a more robust mix of both residential and commercial property are also highest on the list, such as Southlake, Coppell and Grapevine. In addition to having high home values, the three aforementioned cities also collect the highest amount of sales tax revenue per resident in the region. High sales tax collections are one indicator of a relatively large commercial tax base.

The previously released analysis on property taxation also used the holistic “total tax base” metric in determining which cities levy the highest effective tax burden on their local economies, as opposed to median home values. Measuring the total tax base on a per resident basis allows for a more accurate comparison across cities and should be used when setting nominal tax rates.

Stay tuned for more information from the Metroplex Bureau’s Local Government Snapshot analysis that aims to shed more light on local spending, taxing and debt so that officials and residents can make more informed, fiscally responsible decisions.

Note: Each city’s 2014 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) provided all information used in our benchmarking analysis, including population figures.

*Cities that did not have their 2014 CAFR published online were included in our analysis using data from their 2013 CAFR.