After voters in conservative Collin County approved a $600 million bond package for Collin College earlier this month, trustees quickly started spending taxpayer money on their campus expansion plans. This week, trustees also confirmed they’ll be using a controversial legal maneuver to expand the college: eminent domain.

The community college’s nine elected trustees voted unanimously Tuesday to use their power of eminent domain to override a citizen’s private property rights and forcibly acquire land they say is needed to build a campus in Wylie.

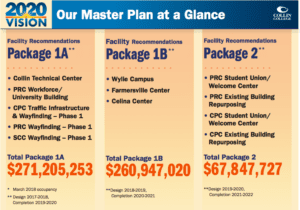

The construction is part of the college’s $600 million “Master Plan” that includes multiple new campuses plus additions and upgrades to existing ones.

Trustees authorized spending $1.34 million – the property’s appraised value – plus costs associated with the eminent domain proceedings to seize 9.9 acres of land adjacent to property in Wylie the college already owns. That’s three times the land’s market value, according to trustees. The current owner has turned down the college’s offers to buy her property.

“The District has been unable to acquire the Property owned by Deborah Mulcahy which is essential and necessary to construct these facilities,” according to the board’s agenda.

The board claims “a public need exists to construct, expand, and operate” a Wylie campus and that “it is necessary that the District acquire” this particular tract of land. Trustees demonstrated they’re willing to use any legal means necessary to acquire it.

District President Neil Matkin called the land grab a “true need” not a luxury item, and said trustees are now “actualizing our Master Plan.”

This is the first time the college has ever used eminent domain.

Some Collin County residents question whether they should be using it now – and whether the property is in fact “essential and necessary.”

Darrell Hale, a local business owner and potential Precinct 3 County Commissioner candidate, wonders why the college couldn’t locate the new campus elsewhere in Wylie, where he notes that vacant land with great road access is plentiful.

“I don’t understand the college’s crucial need to seize this land just because land surrounding it was given to them,” Hale said. “They advertised being given land as a selling point for the Wylie campus.”

Trustee Mac Hendricks said he felt bad about using eminent domain, but concluded that the college had exhausted all its options and “we owe it to the people who elected us to exercise that right.”

Trustee Raj Menon, chosen by the board Tuesday to serve as its new Treasurer, disagreed, saying he understood that the property owner’s only objection to the sale was the price, so “I don’t feel so bad about following the law and doing the right thing for Collin” by forcing the sale.

A more important question is whether a “public need exists” for the Wylie campus itself as proposed.

With the last tract of land to be seized, trustees are aiming to bring the size of the Wylie campus to 98 acres – comparable to the college’s campuses in Frisco (90 acres) and Plano (100+ acres), cities with three to six times the population of Wylie.

It’s just one part of a massive expansion plan authorized by passage of the college’s $600 million mega-bond package. Yet the election results were hardly a mandate from Collin County voters. Only 33,558 of the county’s 531,000 registered voters actually voted for the bond proposition, which passed by a 56 to 44 percent margin.

And voters weren’t given the opportunity to vote separately on each of the plan’s projects, like the Wylie campus – just one vague, all-or-nothing proposition.

Collin County Judge Keith Self wrote in a recent commentary that it’s easy for well-intentioned government officials to say “yes” to every request to spend taxpayers’ money:

“There are certain services that a local government needs to offer its citizens, but taxpayer funding isn’t limitless. Let’s not lose sight of what budget items serve true needs versus wants.”

Trustees expect the land seizure proceedings to take about four months, with a special commissioners’ hearing probably in early September.

At the end of the process, Collin College trustees are likely to have acquired – at taxpayer expense and through means deplorable to most residents – an overpriced piece of land for an oversized campus that the vast majority of Collin County taxpayers didn’t vote for.

Collin County residents with questions or concerns about the college’s expansion plans can contact the Board of Trustees via the Collin College website.