Redistricting is still more than a year away, but Texas lawmakers have been touring the state for months, discussing the decennial map-drawing process and listening to residents’ concerns.

Members of the Texas House Redistricting Committee began holding field hearings last September to generate awareness and solicit public input.

“We hope to have the most transparent redistricting process in the history of Texas,” Chairman Phil King (R–Weatherford) said at a recent public hearing in Plano. “It’s a huge process and a very important process.”

The U.S. and Texas constitutions require a redrawing of voting district boundaries after every 10-year census, impacting federal, state, and local districts.

The simple objective, King said, is to balance out populations among the districts as they change, guaranteeing equal voter representation—the principle of “one person, one vote.”

But the process isn’t so simple, he explained.

“We also have to be very careful that we don’t violate the federal Voting Rights Act,” King said.

The VRA requires that a district design can’t have the purpose or effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on the basis of race, color, or language group.

Lawmakers must also apply “traditional redistricting criteria” that include keeping together “communities of interest” and drawing “compact” districts—a tremendous challenge in Texas because we are such a large state and our population density is so varied across the state, King said.

Partisan interests also play a big role in the political map-making—but not the biggest role.

“The No. 1 priority in all these sessions is incumbent protection,” said local conservative activist Mike Openshaw at the Plano hearing. “The second priority is partisanship.”

Actual map-drawing won’t begin until census data is received next year, King said.

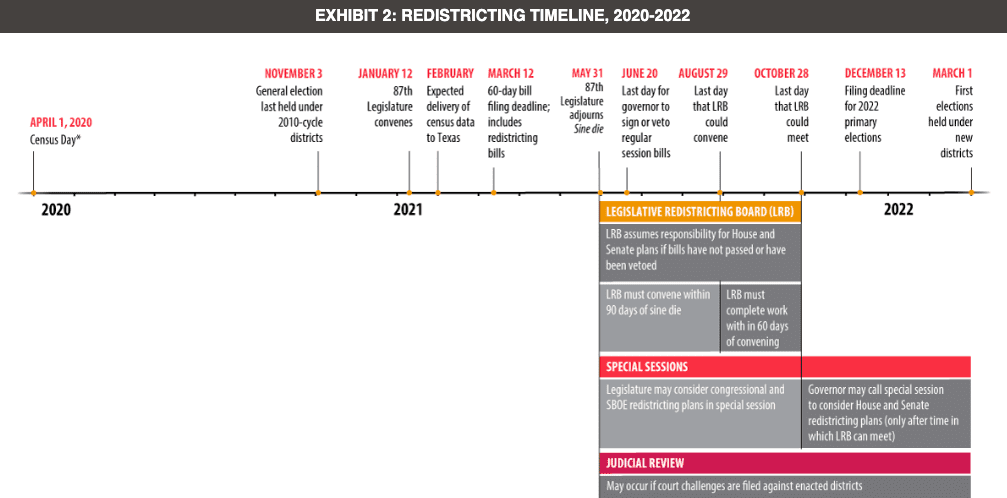

Census data must be delivered to states by April 1, 2021. The Texas Legislative Council will enter the data into a computer program designed specifically for creating district maps, then lawmakers—and the public—can access the program and begin to draw possible maps.

Lawmakers will have until the end of the legislative session on May 31—about 60 days—to complete all of the congressional and state House, Senate, and Board of Education district maps.

“It’s a very short window,” King said.

Redistricting maps are just like any other bill, King said. Lawmakers can propose maps, and they will be posted online for anyone to view, along with supporting data.

The state’s Texas Redistricting website describes the legislative process:

Congressional and State Board of Education (SBOE) district bills may be introduced in either or both houses; senate and house redistricting bills traditionally originate only in their respective houses. Following final adoption by both houses, each redistricting bill is presented to the governor for approval. The governor may sign the bill into law, allow it to take effect without a signature, or veto it.

If the house or senate redistricting bill fails to pass or is vetoed and the veto is not overridden by the legislature, the Legislative Redistricting Board (LRB) is required to meet. If the congressional or SBOE bill fails to pass or is vetoed and the veto is not overridden, the governor may call a special session to consider the matter.

LRB members are the lieutenant governor, speaker of the House, attorney general, comptroller, and land commissioner.

Once the maps are adopted, they can still be challenged. In fact, given the state’s competing political interests, it would be “almost unprecedented” if at least some redistricting plans didn’t wind up in court, according to the Texas Comptroller’s Redistricting 101 site.

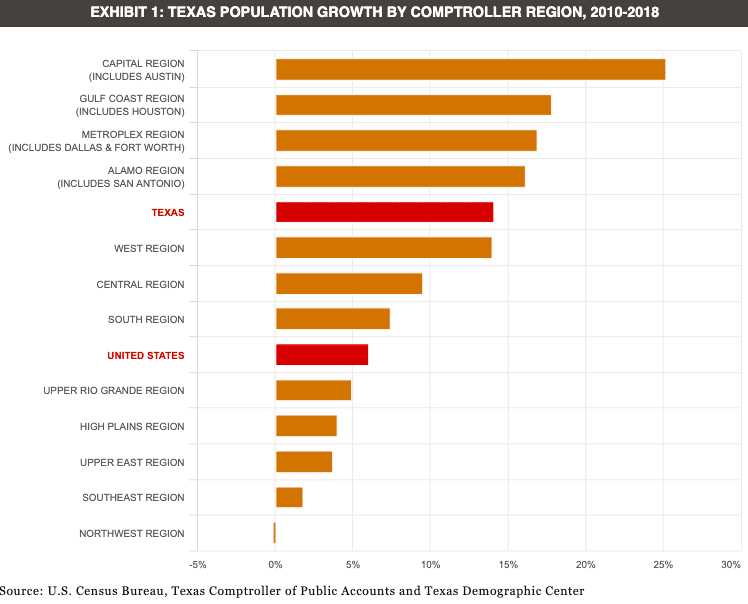

Due to the state’s high population growth—about 15 percent since 2010, more than twice the national average—Texas is expected to gain three new congressional seats. Fast-growing areas of the state will also gain representation in the state legislature.

Local level districts are also redrawn, including county commissioner, constable, and justice of the peace boundaries, as well as single-member city and school board districts.

The Senate Select Committee on Redistricting has met once in Austin to hear invited testimony.

The House committee has hosted public hearings in nearly a dozen cities during the past five months. King said they will continue soliciting input throughout the process and encouraged Texans to visit the redistricting website and contact committee members with questions and feedback.