Texas has been detaining illegal immigrants at an increased clip, but what happens after they are detained? A Texas Scorecard investigation of how illegal immigrants are being processed revealed an opaque self-dealing and self-sabotaging process.

Since December, the planning and execution of the military aspect of Operation Lone Star (OLS) has come under fire. Now, the judicial aspect of Governor Abbott’s border security operation is being questioned.

Brian Gildon, a citizen who has observed part of OLS’ judicial aspect, recently outlined OLS’ conflicting nature to Texas Scorecard. Gildon believes that while the state of Texas has attempted to concentrate taxpayers’ money on the border problem, that money is being used to undermine the state’s efforts after illegal immigrants are apprehended.

Texas Scorecard has reported on Texas soldier’s paycheck hardships; bureaucratic turnover and inexperience at the Texas Military Department; supply issues; forced vaccination; and internal concerns ranging from sexual assault to punishing soldiers through physical exertion.

Our investigation of OLS’ judicial aspect has uncovered allegations that a high-ranking official of a taxpayer-funded nonprofit corporation (which provides illegal border-crossers with legal defense) has been strong-arming defense attorneys to go against their clients’ wishes and keep them in jail. This would effectively sabotage Operation Lone Star.

If illegal immigrants want to plead guilty and “go home,” why is the state of Texas delaying that resolution?

The Allegation

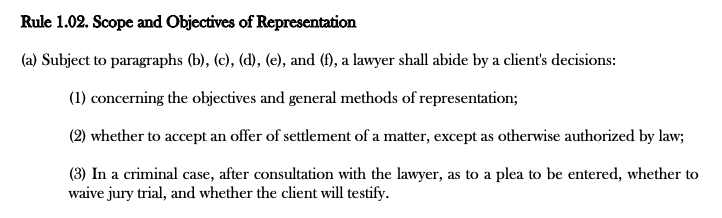

The Texas State Bar Association’s “Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct” clearly state that “a lawyer shall abide by a client’s decision” when it comes to the objectives of the legal representation, including settlement offers and pleas. The legal ethics rule is shown below in full:

Defense attorney Sylvia Delgado has filed a complaint stating that Philip Wischkaemper, chief defender at the Lubbock Private Defender Office (LPDO), is pressuring attorneys to do the opposite.

“I and other defense counsel have been discouraged from pleading our OLS clients either guilty and even nolo contendere [no contest],” Delgado told Texas Scorecard.

Delgado was getting paid by LPDO for her work defending those arrested during Operation Lone Star. “That’s part of why I have been so reluctant to not follow their directives, because I don’t want to lose my income.”

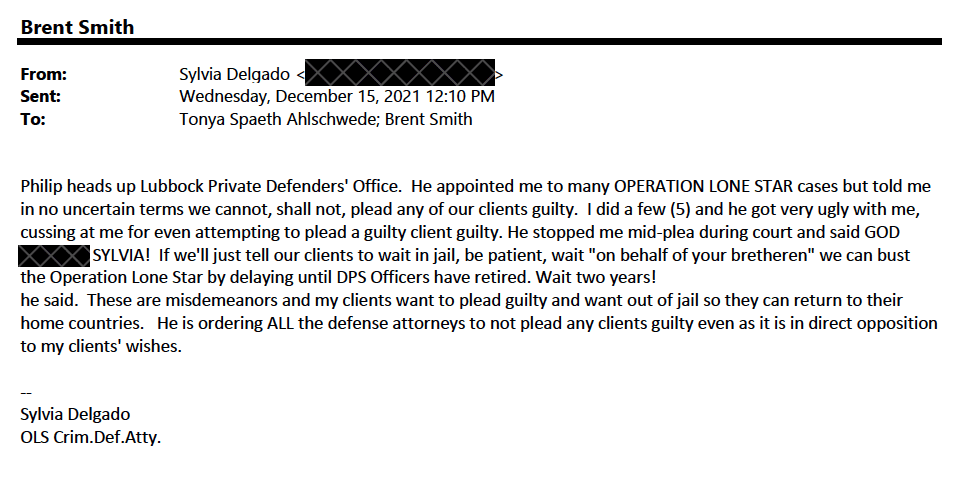

After Texas Scorecard sent open records requests to Kinney County, which borders Mexico, we obtained a December 15 email in which Delgado informed prosecutors of Wischkaemper’s actions.

“[Philip] appointed me to many OPERATION LONE STAR cases but told me in no uncertain terms we cannot, shall not, plead any of our clients guilty,” Delgado wrote. She further alleges that after she plead some of her clients guilty, Wischkaemper “got very ugly with me, cussing at me for even attempting to” plead a client guilty.

He even stopped me mid-plea during court and said … “If we’ll just tell our clients to wait in jail, be patient … we can bust the Operation Lone Star by delaying until DPS Officers have retired. Wait two years!”

Delgado said she was following the wishes of her clients when pleading them. “They told me in no uncertain terms, ‘I want to plead guilty. I want out of jail,’” she told Texas Scorecard. “Me and my interpreter went and spoke with them, and they were very clear. ‘We’re guilty. We came over; we shouldn’t have. I just want to go home. I want out of jail.’”

Delgado alleges LPDO’s Philip Wischkaemper put his personal political interests ahead of her clients’ best interests and tried to stop her from following her own clients’ wishes.

“[On November 18] I went in front of the court, and I was going to plead a guy nolo contendere [no contest], and he was going to resolve his case that day and get his money back,” Delgado recalled. “In the midst of doing that, I got a phone call, and it was Philip and he was not happy with me.”

She said Wischkaemper pushed her not to plead her client, but to “find another way to do this.” She replied that pleading is what her client wanted. “I said, ‘But listen to me, it’s not like he’s going to go to jail here. He is in Mexico. He’s already been deported. He’s already gone home voluntarily. He wants his money back. He put up $1,200. For a person from Mexico, that is a huge amount of money.”

Wischkaemper would not relent. Caught between the state bar’s requirement that she follow her client’s wishes and Wischkaemper’s pressure, Delgado became creative. She asked Judge Kitty Schild if they could change her client’s $1,200 cash bond into a “no fee PR bond,” letting him stay out on bond but return his money. “I just created a new hybrid bond that I’ve never even heard of,” she said. Much to her surprise, Judge Schild agreed, which struck Delgado as odd.

It wasn’t over between Delgado and Wischkaemper. “[Philip] called me and chewed me out for even thinking of pleading another person on the 18th of November. He said, ‘We need to have a phone call.’”

Delgado said the call took place at 3:00 p.m. that day.

“Philip got very hostile toward me [and] was accusing me of moving these cases and not helping the cause,” she said.

Delgado continued:

He said, “Listen, if we don’t plead anybody, if you’ll just talk your clients into sitting in jail, and just wait and say to them, ‘Just be patient, just don’t plead yet, just sit in jail and wait.’ Then, if we all stick together and don’t plead any cases, eventually … DPS officers are going to start retiring. They’re retiring in droves right now anyway, and in two years, when these things go before the court, all those witnesses will have left DPS. There will be no more witnesses, and we will not have folded.'”

Delgado said she had someone come and listen to the conversation. That someone was Brian Gildon, who spoke with Texas Scorecard on February 4 and provided a signed statement of what he witnessed.

“[Philip] told her that she should not be pleading clients and stated it was her job to talk them out of pleading if at all possible, even if they wanted to do so,” Gildon wrote. “He further stated she was ‘acting like a D.A. or a judge’ in her desire to assist in moving dockets faster so she could have more clients released from jail more quickly. His rationale was that even if clients stayed in jail a long time, at the same time Texas Department of Public Safety officers were ‘retiring in droves,’ and so if the defense could slow down the docket/legal process, then there would be no officers to attend trial cases.”

Gildon continued, “He finished with a statement akin to ‘good things can happen if we just hold out long enough.’ At this point, in my opinion, Philip Wischkaemper’s obvious motivation was to grind the Operation Lone Star legal process to a halt until all cases could be dismissed.”

Gildon’s full signed statement can be read here.

Texas Scorecard contacted Wischkaemper’s office, seeking comment about these allegations. No response was received before publication.

In addition to Delgado’s and Gildon’s testimony, Texas Scorecard has also obtained a clip from a December 6, 2021, OLS training video Wischkaemper participated in.

“You’re the brakeman on this train, not the conductor. You don’t need to be pleading these cases unless your client is jumping up and down, screaming, begging to plead guilty,” Wischkaemper said in the video. “Even then, it’s your job to try to back them off and get them to let you work for them to try and get a better result.”

“I understand that the immigration consequences are not really all that severe if they come into play at all, but that’s not the point,” he continued. “The point is that we have to represent these folks as aggressively as we can.”

Delgado made it clear to Texas Scorecard that Wischkaemper was wrong. “I was an ethics attorney. I worked for the state bar, taking lawyers to court for their bad behavior. I know bad illegal behavior when I see it,” she said. “It is an ethical violation for me to not follow my client’s wishes. And it is, in fact, an ethical violation for someone else to interfere with me following my client’s wishes.”

Delgado said she contacted the State Bar of Texas and informed them of Wischkaemper’s actions, was told his actions were an “ethics violation,” and informed that she would be in violation if she went along with Wischkaemper’s misconduct as well. She said she filed a “formal grievance” with the bar against Wischkaemper on December 15.

Texas Scorecard obtained a copy of Delgado’s complaint, with a timestamp of 12:21 p.m.

Earlier that morning, Wischkaemper sent an email to Kinney County Judge Tully Shahan. “I am removing Ms. Delgado from the cases that were on the docket this morning and will have them reassigned to new attorneys by the end of the week,” Wischkaemper wrote. “I have concerns about the notice to Ms. Delgado’s clients who did not appear at the docket this morning.”

Delgado shot back that afternoon, requesting a hearing. “Philip is acting in a retaliatory fashion against me in this and many other instances because I plead [sic] five clients guilty.” She reiterated her charge that Wischkaemper had “directed me and all the OLS defense counsel to refuse to plead our clients guilty even if they are guilty and even if it is their desire (and it is) to plead guilty.”

Texas Scorecard sought comment and confirmation from the State Bar of Texas about Delgado’s grievance. Claire Reynolds, public affairs counsel with the bar, said their office could not confirm “whether such a complaint exists.”

“It can take several months for the whole process to be completed,” she said, explaining that after a grievance is filed, the bar has 30 days to review and either “dismiss it or upgrade it for a fuller investigation.” If upgraded, the accused attorney has 30 days to respond. The chief disciplinary counsel for the bar then conducts an investigation into whether there is reason to believe professional misconduct took place. The matter is then either presented to a grievance panel for a hearing or proceeds to litigation.

It would be one thing for a private law firm or private attorneys to engage in such behavior. However, Wischkaemper and the Lubbock Private Defender Office are being paid by Texans for their OLS work.

Taxpayer Funding to OLS Defense Balloons

During a July 26, 2021, meeting, the board of the Texas Indigent Defense Commission (TIDC), a state body whose mission is “protecting the right to counsel, improving public defense,” awarded a grant of more than $225,000 taxpayer dollars to LPDO for the purpose of providing indigent defense for those arrested during Operation Lone Star.

TIDC states that indigent defense “refers to the legal requirement under the U.S. and Texas Constitutions and Texas statute for the government to provide an attorney and other defense costs on behalf of adult defendants and juvenile respondents whose life or liberty are at stake and who are financially unable to employ an attorney or pay other defense costs.”

TIDC Executive Director Geoff Burkhart explained to TIDC board members what LPDO’s role would be during the July meeting. “[LPDO] would help recruit attorneys for Operation Lone Star. Once a magistrate decides that somebody is indigent, they would actually assign the attorney to the case. They would connect the attorneys with resources.”

On August 19, TIDC increased LPDO’s funding to more than $1.4 million.

Then, on October 1, the TIDC board granted an additional $9.5+ million of state taxpayer monies to LPDO.

Created in 2011 by the Texas Legislature, the TIDC is led by a 13-member board—comprised of appointees from the governor’s office, the state Senate, and the state House—and 12 staff members.

Six of the current board members are appointees of Gov. Abbott, of which four are judges. The judges are the Honorable Missy Medary, Richard Evans, Vivian Torres, and Valerie Covey. The other two Abbott appointees are Alex Bunin and Gonzalo Rios Jr. Also present on the board is State Rep. Reggie Smith (R–Van Alstyne), who was endorsed for re-election in 2018 by Abbott.

A voice vote was held to approve the first batch of taxpayer monies to LPDO at the TIDC board’s July 26 meeting. No one was heard voting no. That initial approval of $225,000 was upped to more than $1.4 million during an August 19 meeting. It once again passed by voice vote. No one was heard voting no.

At TIDC’s October 1 emergency meeting, LPDO was granted the $9.5 million grant. In the same month that TIDC was funneling money to indigent defense, the Texas Military Department and Texas comptroller were scrambling to get OLS soldiers paid on time.

Calm Before the Storm?

Gildon said things changed after Delgado filed her grievance. “Now they’re allowing them to plead.”

However, LPDO appears to be consolidating and amassing more power with Wischkaemper at the helm.

“They have restructured LPDO, restructured everything,” Gildon said. “What they’re doing is they’re creating public defender offices all over the place, but their approval is under LPDO, [directly under] Philip Wischkaemper.”

It’s easy to envisage such a shift leading to the firing of all private attorneys, placing control in public defender offices. Gildon worries about this possibility and that a Wischkaemper-like mandate to keep illegal immigrants in jail to stress DPS could return. If this happens, Gildon said “there needs to be some serious investigation [at] the governor level.”

“Philip is now in charge of allocating all OLS indigent defense commission funds for public defender offices statewide, despite TIDC’s knowledge of his misconduct,” Delgado told Texas Scorecard February 8.

During the July 26 TIDC board meeting, board member Judge Evans expressed a desire for LPDO to eventually pay back the taxpayer money being given to them. “We need to be sure if we’re going to give money to Lubbock and to Rio Grande Legal Aid, we request that to be paid back if the governor sees fit to fund this.” It’s unclear how Evans’ suggestion would work.

Texas Scorecard contacted TIDC Executive Director Geoffrey Burkhart to ask if TIDC would have LPDO pay back all taxpayer monies received in light of these allegations. We also asked if TIDC and the board were aware of these allegations. No response was received before publication time.

Texas Scorecard also sent an inquiry to the governor’s office. No response was received before publication time.