Texas election officials are developing a new program to improve the accuracy of the state’s voter rolls by comparing them with voter lists in other states, preparing for a possible exit from the controversial ERIC “crosscheck” service they currently use to identify voters who register and vote in multiple states.

The Texas secretary of state, who is the state’s chief election official, announced last week that longtime Elections Director Keith Ingram will now serve in “a newly-created position to develop and manage an interstate voter registration crosscheck program.”

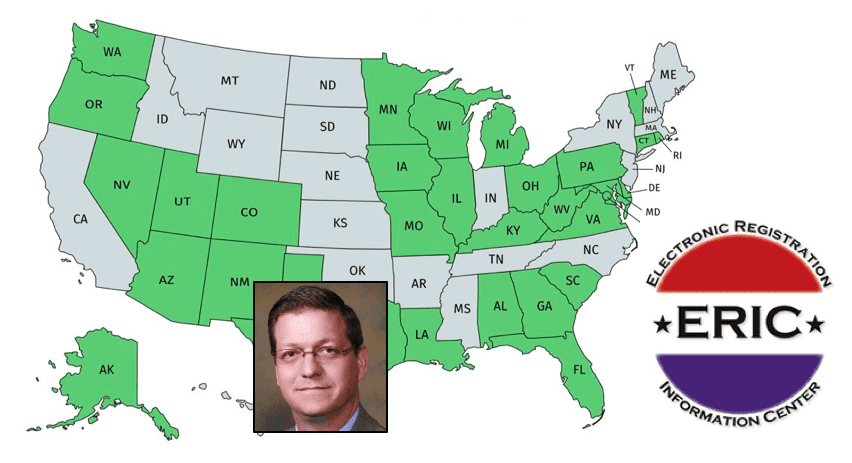

The announcement comes as several other states are leaving ERIC, the Electronic Registration Information Center.

Republican Party officials and election integrity advocates are pressing Texas to withdraw from the program as well, citing concerns about costs, data security, and possible partisan access to voter data.

SOS spokesman Sam Taylor told Texas Scorecard that other states would “absolutely” be invited to participate in Texas’ new crosscheck program.

“Particularly because it’s required by statute,” Taylor said. “Sec. 18.062 requires Texas to ‘cooperate with other states and jurisdictions’ to develop such cross-check systems.”

Currently, that system is ERIC. Should legislation pass that removes Texas from ERIC, or should a critical mass of states leave ERIC (which would reduce the usefulness of the data we receive from the partnership), Texas has to be ready to comply with this requirement in state law.

Texas Election Law Requires Crosschecks

Texas Election Code requires the state to participate in an interstate crosscheck program that compares “voters, voter history, and voter registration lists to identify voters whose addresses have changed.”

At this time, ERIC is the only such program. Texas joined ERIC in 2020. The state originally planned to participate in a free crosscheck program run by Kansas officials, but it was driven out of business by an ACLU lawsuit.

Yet Republican lawmakers have filed legislation in the House and Senate that would have the effect of eliminating ERIC as a crosscheck option by setting limits on costs and data-sharing.

The legislation also prohibits Texas from participating in a crosscheck program that requires “any additional duty” of the state.

ERIC’s contract requires member states to expend resources sending voter registration information to people the system identifies via driver’s license data as “eligible but unregistered.”

Ingram told lawmakers at a House Elections Committee meeting last week that his office recently spent around $600,000 on one such mailing.

A task force formed last year by the Republican Party of Texas to research the program concluded that “ERIC is not an effective solution for Texas in terms of the number of voter registration records identified and especially in terms of the cost Texas is paying for the information we get.”

About ERIC

ERIC was started in 2012 by the Pew Foundation to help clean up states’ bloated voter rolls. Pew estimated that millions of U.S. voter records were inaccurate, invalid, or duplicate registrations.

Although federal laws require states to conduct regular voter list maintenance, voter rolls often contain deceased or otherwise ineligible people—including voters who move and end up registered (and in some cases, vote) in multiple states.

A secondary aim of the ERIC program is to increase voter registration.

The program is now managed and funded by the member states. Each state is represented on ERIC’s board of directors and pays annual dues ranging from $26,000 to $116,000, depending on population.

About 30 states plus D.C. are ERIC members, but several Republican-led states recently announced they are withdrawing.

Louisiana and Alabama exited ERIC earlier this year, citing concerns about privacy and possible partisan access to voter data.

On March 2, ERIC’s Executive Director Shane Hamlin addressed some of the concerns raised by critics, but it wasn’t enough to persuade other states to stay.

Last week, Florida, Missouri, and West Virginia notified ERIC that they are leaving over concerns about data privacy, board procedures, unnecessary mailings, ERIC’s “potential partisan leanings,” and the program’s failure to require member states to address voters who illegally vote in multiple states.

ERIC Pros and Cons

ERIC’s top selling point is that it’s the only game in town, for now.

“It is the best, most effective way for states to learn about registrants voting twice in multiple states,” said J. Christian Adams, president of the Public Interest Legal Foundation, a law firm dedicated exclusively to election integrity.

“The problem with ERIC is the lack of transparency,” Adams told Texas Scorecard. “The membership agreement violates federal law. Election records are public. The ERIC agreement makes them secret. The Public Interest Legal Foundation has four lawsuits to gain access to these reports in D.C., Alaska, Colorado, and Louisiana.”

Adams and Chad Ennis, director of the Texas SOS Forensic Audit Division, discussed the pros and cons of ERIC during this month’s Texas Public Policy Foundation policy summit.

Ennis said within a recent six-month period, Texas used information supplied by ERIC to remove more than 100,000 people from the state’s voter rolls who had registered in Texas then subsequently registered in another state.

However, Ennis acknowledged that with fewer states participating in the program, especially states with large populations of registered voters, the value of ERIC’s data is diminished.

Democrat-led California and New York (first and third in number of registered voters—Texas is second) have never been members. Fourth-place Florida’s exit leaves another big hole, especially as their snowbird and retiree populations contribute to a large number of two-state registrants.

Until there is a better alternative, Adams said states are “probably better off in ERIC than out” if they want to continue catching voters who are registered and voting in multiple states.

Texas is now set to create an alternative.

With Ingram heading the crosscheck development project, the department’s legal director Christina Adkins will serve as acting director of the Elections Division.

No ads. No paywalls. No government grants. No corporate masters.

Just real news for real Texans.

Support Texas Scorecard to keep it that way!