Over the weekend, Kent Schaffer, one of the special prosecutors tasked with investigating Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, leaked the news that he had secured three felony indictments against Paxton to the press. The New York Times quoted Schaffer defending his prosecution and explaining the terms of the indictments in detail. Given that the indictments were under seal until Monday at noon, it was a very bad sign for the seriousness with which Mr. Schaffer and his colleague approach their duties.

The leaks allowed Paxton’s political opponents ample time to use the indictments to attack him while his supporters were left wondering what the indictments might actually say.

On Monday the indictments were formally unsealed. They are just as bad as the absurd indictments brought against former Gov. Rick Perry.

Measuring just two pages apiece, the three indictments allege the following as felony acts:

- That Paxton referred two legal clients to an investment advisor in his building (and received a referral fee from that advisor) but did not file paperwork beforehand to register as an “investment advisor representative.”

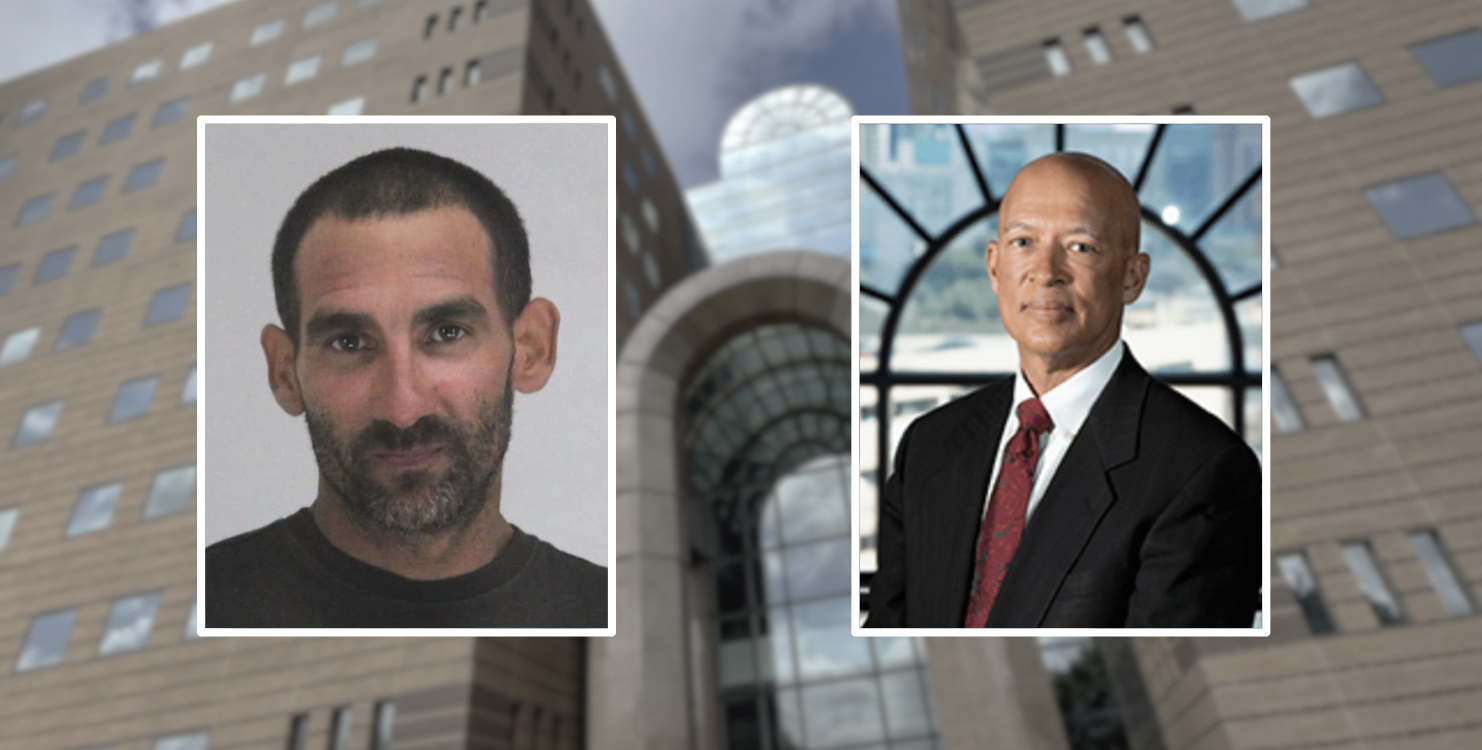

- That Paxton encouraged State Rep. Byron Cook (R–Corsicana) to invest in a McKinney-based company, Servergy, Inc., but didn’t tell Cook that he was receiving compensation from the company or disclose that he was not personally invested in the company.

- That Paxton encouraged Joel Hochberg, a video game developer from Florida who is associated with Cook, to invest in Servergy as well.

Joel Hochberg is a long-time Cook associate who ran the video game development company Rare Ltd. in the 1990s. Hochberg created the popular video game “Battletoads,” which Cook’s company, Tradewest, published.

That’s it. The prosecutors have alleged that Paxton didn’t file some paperwork with the state, and failed to mention to Byron Cook and Byron’s Battletoads buddy that he wasn’t personally invested in Servergy. For those seemingly innocent acts, Cook and the prosecutors want the people of Texas to rip Paxton away from his wife and children and lock him in a cage for the rest of his life.

Attorneys familiar with the securities litigation are rightfully expressing their skepticism about the case. In an interview with Texas Lawyer, former federal prosecutor Bill Mateja explained that failure to register is usually treated as a de minimis matter and enforced through civil fines. “It makes me wonder how they are going to prove this,” San Antonio criminal-defense lawyer Cynthia Orr, who defends people facing securities charges, told the magazine.

The indictment on the failure to register notably does not discuss a required mental state, or explain how merely meeting the definition of an investment advisor representative satisfies the law’s requirement that Paxton illegally “rendered services” as an investment advisor.

Mateja and Orr expressed surprise with how the prosecutors had framed their case. Mateja had expected to see some allegation that Paxton made some fraudulent misrepresentation and was surprised to see the case built around fraudulent omissions.

“These fraud counts are saying he failed to mention certain things to certain investors; so it’s a fraudulent omission case. It’s not a fraudulent misrepresentation case,” he said. “They are saying that it was unlawful for him to fail to mention that he had not personally invested and he would be receiving compensation.”

The distinction is important, explained Mateja, because it’s easier for a prosecutor to prove that someone made a fraudulent misrepresentation than proving a fraudulent omission. Either way, a prosecutor must establish that the misrepresentation or the omission was material.

“The question is: Would these investors—would they have changed their minds based on knowing that information,” said Mateja. “This case is going to boil down to materiality.”

Orr said that the allegation that Paxton didn’t tell the investors that he had not personally invested in Servergy is “strange.”

“How would it be material to an investor that [Paxton] had not invested,” said Orr, an attorney with Goldstein, Goldstein & Hilley. “I would attack it. … How would it make someone invest, where they would not invest had they known?”

The charges seem absurd, particularly given that they carry a maximum 99-year prison sentence. But unfortunately, as Texans have learned from the Delay and Perry cases, being right doesn’t mean that a resolution will come quickly.

It will likely take Paxton years and a mountain in legal fees to clear his name. In the meantime his character will be attacked and he and his family will be the subject of vicious lies. When he eventually wins, out of all the people who attacked him and tried to destroy his life, not one of them will even offer a simple apology. They will have accomplished their goal. The process is the punishment and Paxton is being punished for winning.

This is the criminalization of politics. These vicious tactics won’t stop until those who (unsuccessfully) attempt to ruin others’ careers and reputations through “the process” feel consequence for their actions.