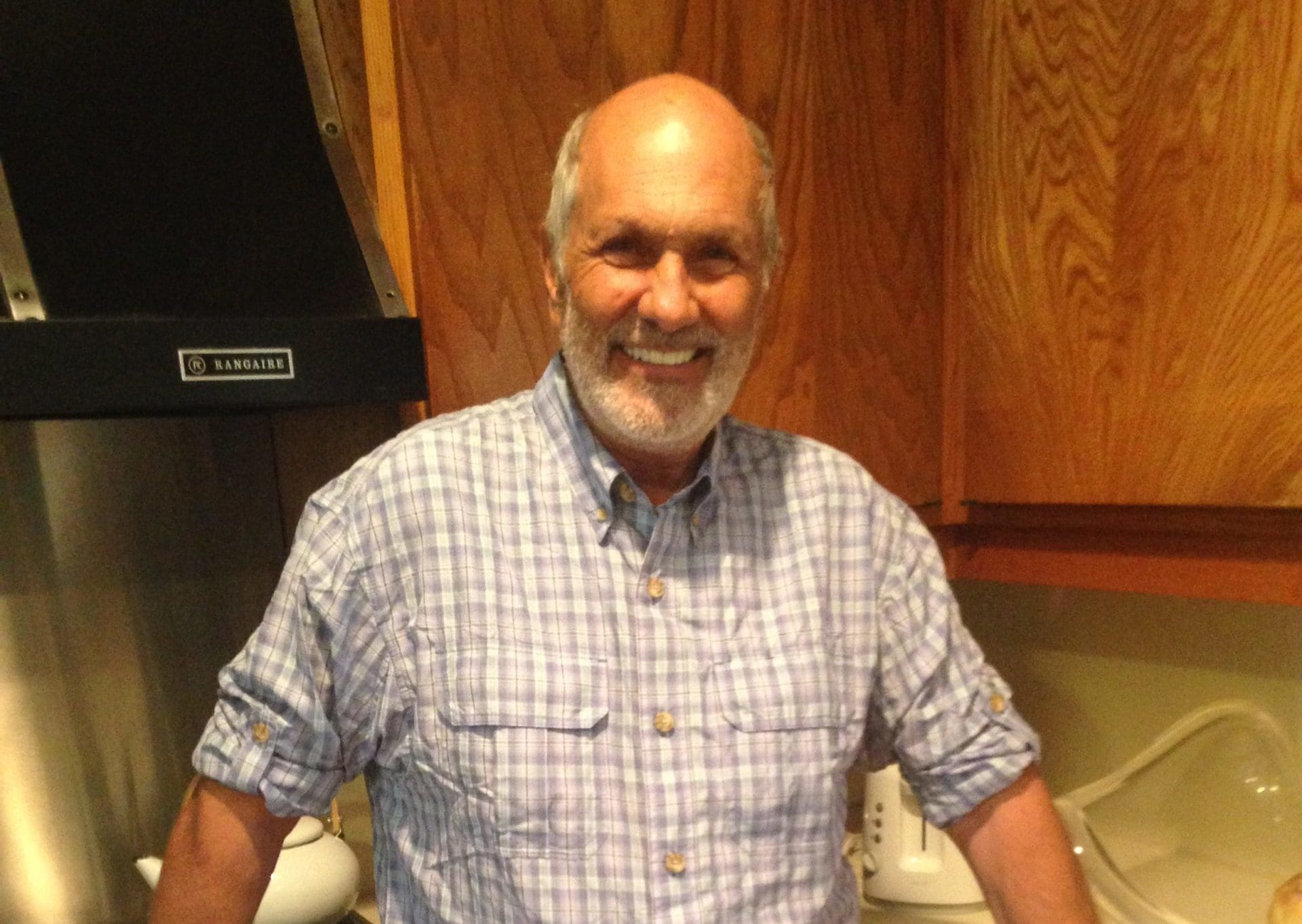

I used to be a registered nurse. I never would have imagined that patients would be treated like this in an American hospital.

On December 12, my mom and sister took my dad, Joseph Ayoub, to The Hospitals of Providence Transmountain Campus in El Paso, Texas. They sent him home with an oxygen tank. They said that since he wouldn’t take remdesivir, there was nothing they could do for him, and to come back if he got worse.

On December 14, I received a phone call that still haunts me. My dad tried to get a referral for Regeneron monoclonal antibodies from a nearby urgent care. Upon arrival, they said he had to go to the hospital because his oxygen saturation was very low. He was taken to The Hospitals of Providence Memorial Campus.

I immediately jumped on the next flight out and arrived in El Paso by late afternoon. I arrived at the hospital, and the fight of my life began.

Providence Memorial had not allowed my mom to see my dad. We kept asking why he had to be alone, and they kept saying COVID. We offered to sign a waiver, but they said the isolation wasn’t to protect us, it was to protect the community from us.

We asked for monoclonal antibodies, and the doctor said he would order them. We would later find out this didn’t happen. They were not ordered, and even if they had been, they would not administer them to in-patients. Monoclonal antibodies were only available on an outpatient basis.

We stayed at the hospital during waking hours, on FaceTime with my dad. We wanted him to know we were nearby, hoping it would help his anxiety. They tried to make us leave, but we refused.

The next day, when I called my dad, he told me he had been up since 4 a.m. He tried to call a nurse to use the bathroom and get some coffee and water. His requests were ignored, and he sat in a dark room until after 9 a.m. His anxiety kept increasing because he was alone.

He kept asking for my mom. We contacted the charge nurse and the administrator on duty, asking for permission to see him in person.

On Wednesday the 15th, when he was still awake, he was transferred to the ICU because his blood pressure had become unstable. We were told by Dr. Rowley, the intensivist, that his prognosis was substantially worsened because he was unvaccinated. We were also informed that the reason we were unable to visit my dad in person was because we were unvaccinated.

My mom was allowed in the room only for 15 minutes while the doctor explained how my dad was going to be assigned the status of DNR (Do Not Resuscitate) if he did not change his DNI (Do Not Intubate) status to allow intubation. After that terrorizing conversation, my mom was forced out of the room again, and my already anxious dad was back in isolation.

They continued to isolate him. Into day four, my dad’s vital signs were stable, and the hospital said they were transferring him back to the “telemetry COVID” floor. He seemed to be in better spirits, joking around with the nurses in his usual form. He thought he was going to get to see my sister because of her vaccination status, but once she arrived, they denied her in-person visitation.

We reminded them what they said about our vaccination status and that with my sister, that issue was resolved. They changed their story again and denied vaccination status being the reason for my dad’s isolation. My dad’s anxiety rose again, so they gave him Ativan three times, despite his negative reaction to it. Rather than a calming effect, it agitated him, resulting in panic attacks.

The negative reaction to the Ativan changed my dad. He was pulling his mask off, which was causing his oxygen level to drop, and the respiratory therapist and nurses were yelling at him to keep it on. They asked him if he wanted to die, shouting that he was going to be intubated. I heard all this horror on FaceTime.

He was so anxious, they told us he would calm down when the nurse was in the room and he’d grab her hand. They finally decided to let my mom visit him. What she found was a dark, long room with no drinking water, no television, and no soap to wash his hands.

They gave him other antipsychotic drugs as well, which we discovered through the billing statements.

On top of all this, we discovered that on the night of December 15, the hospital didn’t feed my dad dinner. We called and asked about that and were given three different stories: “It was accidentally delivered to the wrong room. … I thought he wasn’t able to eat because of a procedure tomorrow. … I thought his dinner was chicken broth.” He never received broth, and we had asked for it to help give him protein.

We had to get food for him ourselves.

My dad was inconsolable. His primary care doctor told us the medications that were administered to my dad were the cause of his delirium and panic attacks, and that they would be in his system for another 12 hours. He said we’d have to intubate because his blood gasses were low because he was pulling his oxygen mask off. We were terrified. I knew once he was intubated, that was it.

He was intubated on December 18, his fifth day in the hospital. They allowed my mom to continue seeing him at this point, but when she arrived on Sunday, she noticed his left foot was cold and was concerned about a possible blood clot. After notifying Nurse Deedee, my mom received warm blankets for my dad. The nurse either didn’t think or didn’t care that only one foot was cold.

The respiratory therapist came in and my mom expressed her concerns about his foot. The therapist checked his pulse and said it was fine. When Dr. Rowley came in that afternoon, my mom brought up his foot again. He replied they were looking a little “dusky” and that he would order a Doppler test.

My mom left at about 9 p.m. When she returned the next day, the Doppler had not been done, and my dad’s foot was purple. My mom took a photo of it and sent it to me. I called the administrator on duty, and the Doppler was done shortly after, and they put my dad on heparin. They told us he would need a procedure to break up the clot.

The clot procedure did not happen for another 24 hours. Color returned, but a couple of days later, they found gangrene and had to amputate half of his foot.

Before the procedure, my mom was told she was no longer allowed in the room, and we were told we were being limited to two update calls per day. During these calls, we found out that most of the nurses helping my dad were traveling nurses. We could not depend on them to call us at our appointed times, and we had to call repeatedly to reach anyone.

They would also do “sedation vacations” and “spontaneous awakening trials” without his family at his bedside. My dad’s vital signs would go nuts and they would tell us he is not tolerating the tests, which would bring him off the vent. I repeatedly said that if they would allow us in the room, he would do better. They refused; we already knew COVID wasn’t the reason, because they allowed my mom in the room before.

The doctors and nurses would often tell us they were going to start some medication or do some procedure. When we’d question it, they would tell us it was the only choice we had if we didn’t want him to die. With every medication and every procedure, he declined.

There are many more details of our horrific experience at Providence Memorial Hospital in El Paso—too much to cover—so I’m going to skip to the end.

About two weeks before he died, we finally had an attorney write a demand letter, which got us in the room within 24 hours. We found filthy floors in a room that had not been cleaned for 36 days. There was urine on the floor, other fluids, dirt, and who knows what else. This is the same room they did a bedside tracheotomy in. Meanwhile, unknown infections would appear.

We spoke with housekeeping, and they told us that they were not allowed to clean because of “COVID.” He also had three bedsores, even though we were told the nurses had been moving him every two hours. Once we got into the room, we recognized that it was rare for anyone to even go in there. When they did, most often they were not moving him.

For the hospital, they didn’t consider it best for my dad to have his family at his bedside to advocate for him and keep his anxiety down. They preferred to—multiple times—give him medication that he had adverse reactions to; one was stated as an allergy on his records.

They put him on a portable ventilator to change central lines. When he came back from that procedure, his oxygen saturation levels were in the high 70s, up to 85 percent, compared with being in the 90s earlier, when he was moved out of the room. This is when they had to “paralyze” him with medications. That paralytic prevented his diaphragm from moving. After that, his organs began to shut down.

They euthanized my dad in front of our faces. He was dehydrated, deprived of food, isolated, and ignored because he was an “unvaccinated COVID patient.”

We would ask questions throughout the entire process, and their answers were simply, “This is what happens with COVID.”

This is a commentary published with the author’s permission. If you wish to submit a commentary to Texas Scorecard, please submit your article to submission@texasscorecard.com.