At never before seen levels, Americans are losing faith in government. This troubling development is symbiotically paced with a growing lack of trust in the mainstream media.

According to Gallop, 60 percent of those polled said they “have little or no trust in the media to report the news fully, accurately, and fairly.” This is an institution once expected to hold governments accountable.

Everyone knows there’s corruption in government. Schemes of cronyism and self-enrichment with taxpayer resources are legion. But when the media is silent—or worse, used to deflect attention from the scheming of politicians—trust plummets.

In Harris County, when it comes to the media acting as a watchdog, we have a classic case of the dog that’s not barking.

They Live

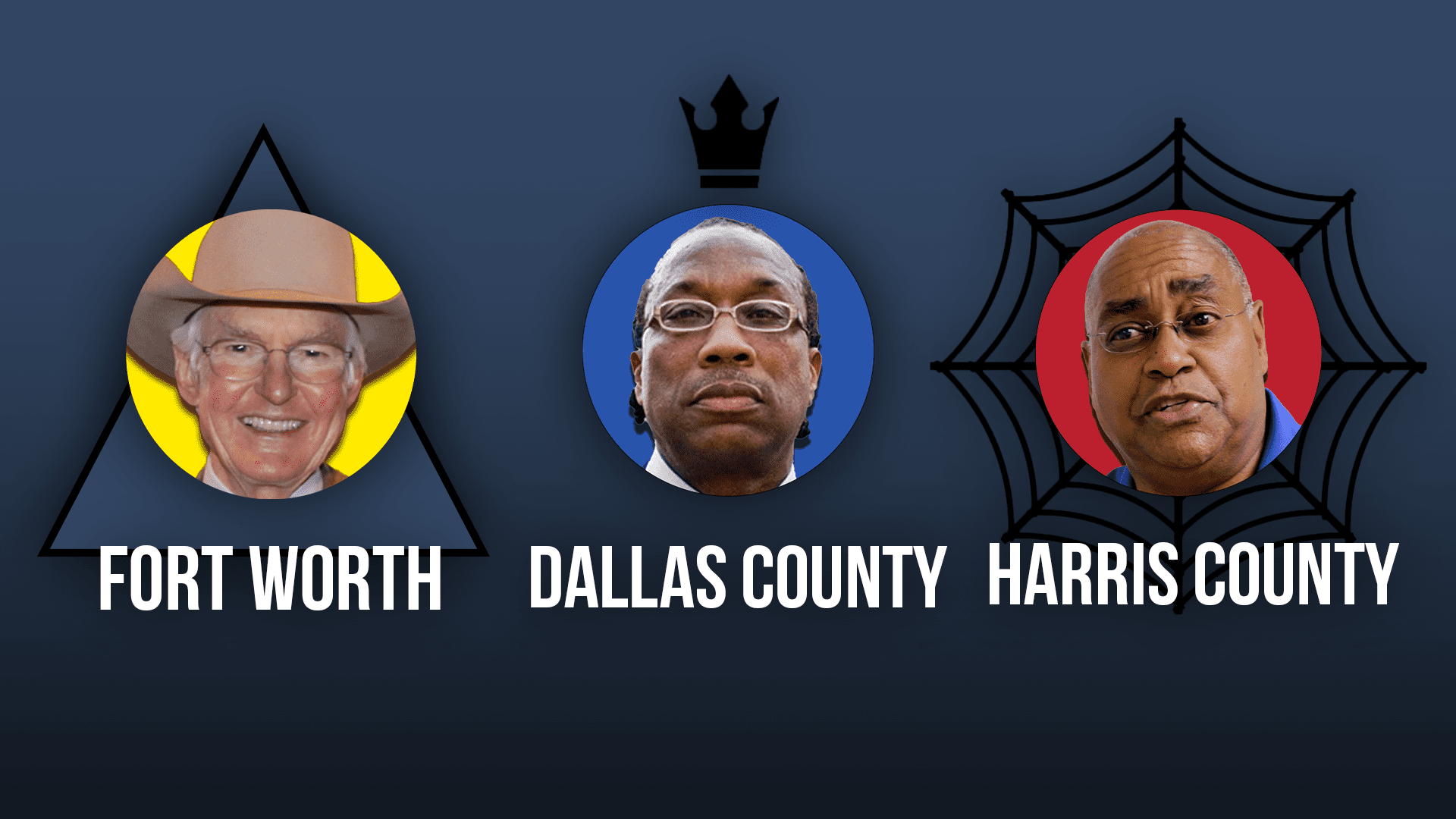

Political power structures, networks of politicians and their backers that influence or control government, take different forms depending where you are in Texas.

D Magazine has covered Fort Worth’s “pyramid of power,” where citizens are in the bottom layer and the Bass brothers—four wealthy businessmen and influential donors—sit at the very top.

Such power structures don’t solely reside in cities. Commissioner John Wiley Price (D) in Dallas County has spent many years building his monarchy, with himself as king.

Texas’ largest county isn’t exempt from this kind of political power structure.

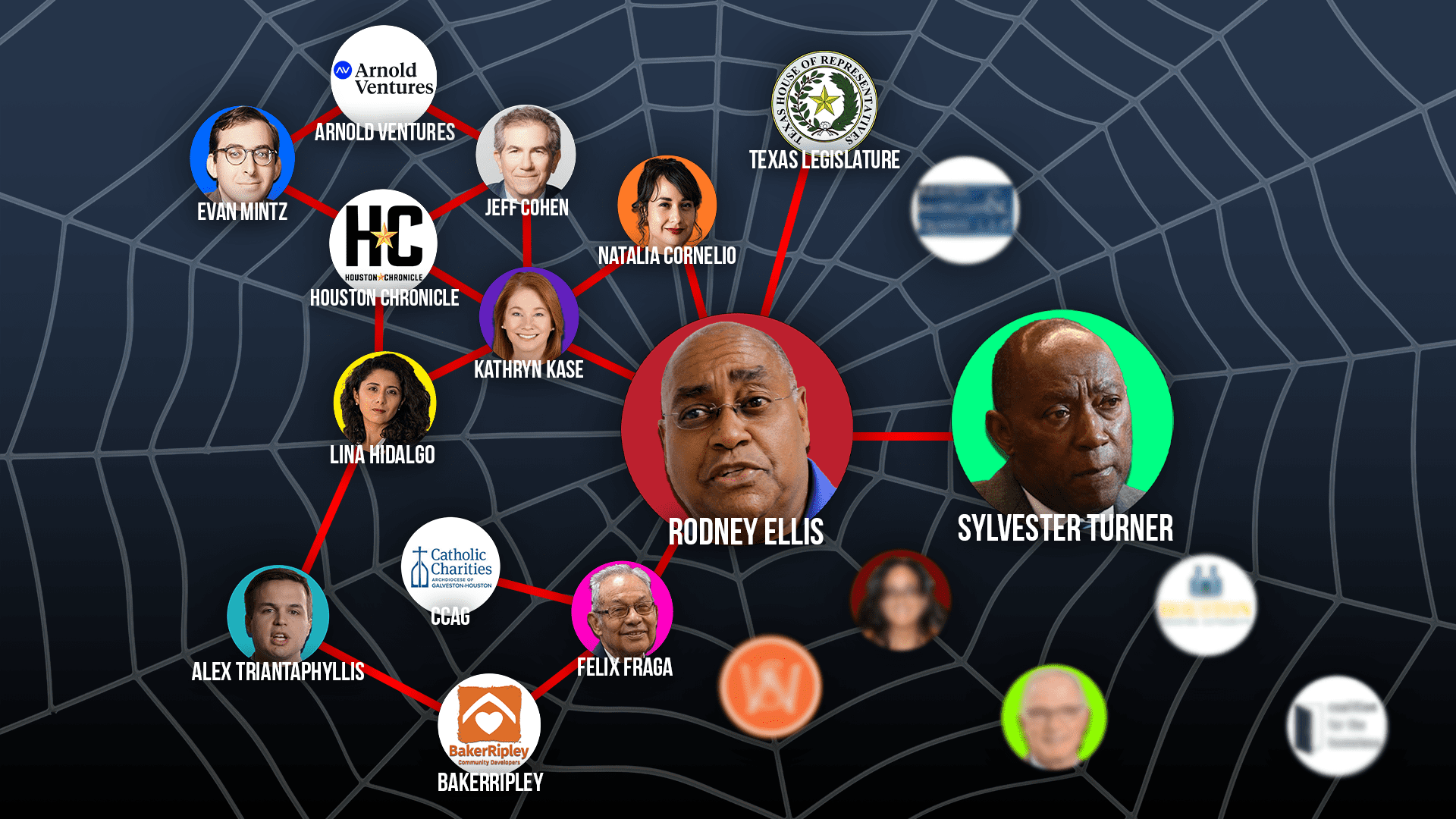

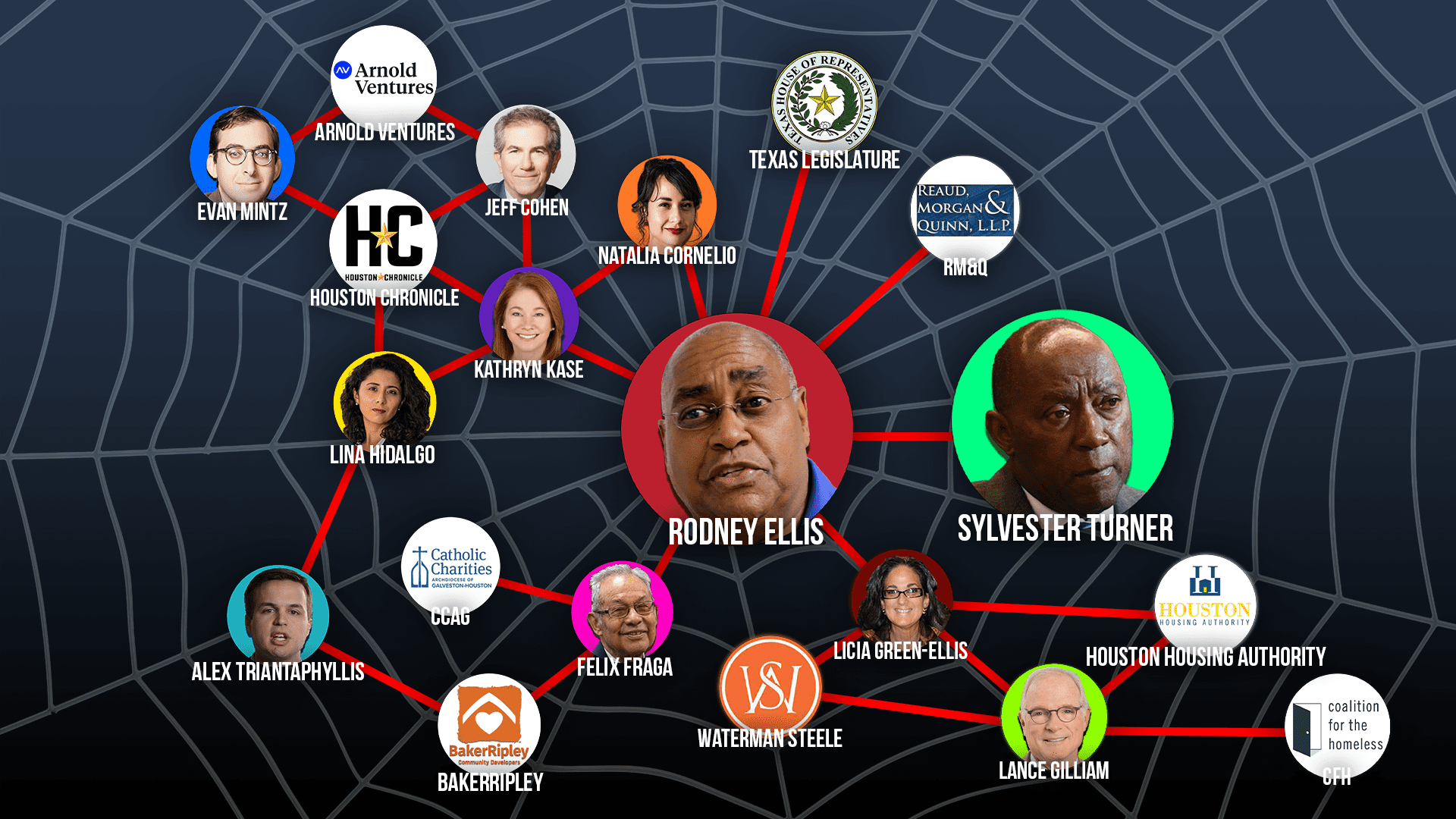

“[Harris County’s] equivalent to those figures would be, at this point, probably Rodney Ellis,” Charles Blain, of Houston-based nonprofits Urban Reform and Urban Reform Institute, told Texas Scorecard. He’s referring to the current Democrat County commissioner in Precinct 1, who, just like Dallas’ Commissioner Price, wields incredible influence.

But the power structure in Texas’ most populous county doesn’t look like a pyramid or a monarchy; Blain describes it as a spider’s web of relationships, with Ellis at its center.

Texas Scorecard previously reported on incestuous dealings in Harris County that have connections to the Precinct 1 commissioner.

As scandals continue to engulf and embarrass the area, those wanting to clean up Harris County, or prevent this level of corruption elsewhere, must understand the power structure that exists around them. Blain insists “having a better idea of these connections allows for a more robust worldview about what is actually going on.”

“I think [citizens] need to know who their elected officials are doing work with, supporting, and supported by.”

He also believes the scandals coming out of the county right now are a feature, not a bug, of the web network in place, as it encourages public servants to reward their friends rather than advance citizens’ interests.

The good news is these power structures can, through time and attention, be overcome. For example, fissures are appearing in Fort Worth’s “pyramid,” and multiple indicators (Tarrant County’s GOP March primary and the Fort Worth City Council’s redistricting fight) suggest the Bass brothers are a power in decline as citizens reassert their self-governance.

Who is Rodney Ellis?

Ellis has been a part of the Houston political scene for decades. To understand how he’s built power over time, one must first understand the area which Blain described as having a “business-centered” culture.

“It’s never really about where you came from, what your last name is, who your parents are, what they do, or anything like that,” he said. “It’s always kind of focused on what you brought to the table or what you can bring to the table.”

While successful businesses focus on what skills and ethics you “bring to the table,” others focus solely on who you know. And in Harris County, there are many who know 68-year-old Ellis. “If there’s something that he wants done or wants accomplished, he certainly has no shortage of friends that he could look to,” Blain said.

His power skyrocketed to its peak once he became a commissioner. This is not unusual. While often overlooked, county commissioners in Texas wield much power close to home. This has been seen with Commissioner Price in Dallas County. And in Tarrant County, it appeared outgoing Commissioner J.D. Johnson (R) could steer retiring County Judge Glen Whitley (R).

But Ellis wasn’t always a commissioner, and his web of power has taken many decades to weave.

Ellis attended and graduated from University of Texas Law in 1979. He worked as an aide to then-Lt. Gov. Bill Hobby during this time, and he later worked for Railroad Commissioner Buddy Temple as legal counsel. He then served as the chief of staff for then-Congressman Mickey Leland (D), who was reportedly a close friend.

In 1983, Ellis was elected to Houston City Council in District D. He served three terms. After winning re-election to city council again in 1989, the Houston Chronicle reported Ellis quit before his new term began and that he ran unopposed for state senate in District 13 during a special election.

During his time on council, it was widely reported Ellis supported a program giving advance warning of police sweeps of an area infested with drug activity—then known as “Death Valley.” This program was criticized at the time as ineffective. Also widely reported was Ellis’ support for creating a citizens police review board in the city. Such boards have since been criticized as ineffective at holding police accountable, and distracting citizens from going to the very elected officials who have power over law enforcement.

Ellis served in the Texas Senate from 1990 to 2016, and earned a career F rating for his votes on spending state taxpayer monies, as tracked by Texans for Fiscal Responsibility since its inception in 2007.

After Harris County Commissioner El Franco Lee passed, Ellis swapped his state senate re-election bid for the vacant seat, which he won unopposed in 2016. Most might look at this as a demotion, but wielding power in the county is easier and more lucrative. “I think he’s gonna be there until he no longer wants to be,” Blain said.

Serving at these three different levels of government allowed Ellis to weave a web of influence throughout the area.

“Through the years, he amassed a lot of power just by helping other Democratic elected officials, particularly younger ones, who have come up through the system and wanted to get into office, or to become a staffer, or consultant,” Blain said. He pointed out Ellis helped many of the judges in the county who won in 2016 and 2018. This was part of a pattern of Ellis helping many get elected across the county, working as a sort of kingmaker similar to Dallas’ John Wiley Price.

“You amass a lot of friends by doing that, and in the end, a lot of favors if you need them,” Blain said. “When [Ellis] wants to see something done, he then leans on whoever is in the position to do so.” And if leaning isn’t an option, then he’ll try to “work with” or “convince” whoever can deliver the goods.

How Commissioners Courts Work

If you aren’t familiar, know that county governments work similar to city councils.

One member of the court, the county judge, is chosen by voters countywide, just like the mayor is chosen by voters across an entire city. The other members of the court are made up of four elected commissioners, one per precinct.

The commissioners and county judge spend much of their time setting policy, setting the property tax rate, and deciding how to spend taxpayers’ money.

In order for any action to pass in a commissioners court of five members, at least three must agree for there to be action.

When Ellis first became a commissioner, he was part of the two seat Democrat minority. That changed in 2018.

Ellis’ Web in Action

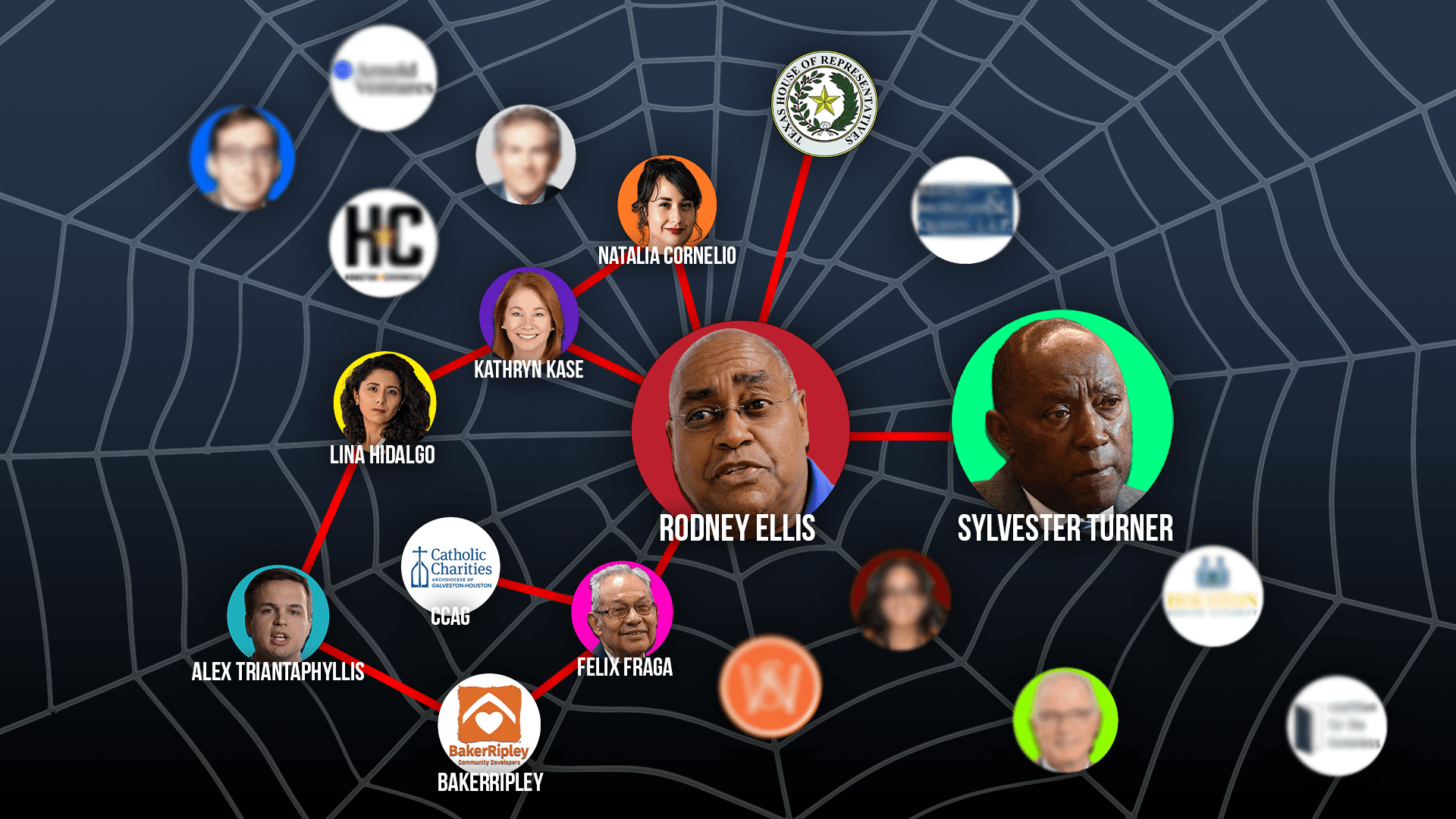

A real world example of how this network operates is County Judge Lina Hidalgo (D), who won the 2018 general election, giving Democrats a 3-2 majority on the county commissioners court. Blain explained that Ellis situated himself in a mentorship position to Hidalgo when she came to power.

“A lot of people joke that he runs commissioners court, and essentially the county, because he has his perspective in her ear.”

As previously reported, Alexander Triantaphyllis, Hidalgo’s chief of staff, previously worked at BakerRipley Community Developers. This is an organization that Ellis has an indirect connection with, and has been receiving taxpayer monies. County Judge Hidalgo’s legal counsel is Kathryn Kase, another former Ellis employee.

Triantaphyllis is one of three Hidalgo staffers indicted in regard to an COVID-19 vaccination marketing program costing county taxpayers $11 million. The contract was with a company—Elevate Strategies—run by a former employee of fellow Commissioner Adrian Garcia (D), Felicity Pereyra. Hidalgo’s staff are alleged to have been looking for an excuse to redirect taxpayer monies to Pereyra, and manipulated county processes to get her organization the vaccine marketing contract over a more qualified bidder.

Judge Natalia Cornelio was assigned to hear the cases against the three staffers, and that’s where this case bumped right into Ellis’ web.

The Texan learned Cornelio once worked for Ellis as Director of Legal Affairs. She was elected judge of the 351st District Court in 2020. Among her donors are Kathryn Kase, Hidalgo’s criminal defense attorney Ashlee McFarlane, and Pereyra.

The indictments against Hidalgo’s staff members came down on April 11. The Texan reported Judge Cornelio recused herself eight days later.

It was recently reported that, on April 13, Triantaphyllis violated one of the conditions of his bond; just one day after it was set at his court hearing.

Ellis’ influence on Hidalgo is also how the county’s controversial bail bond reform, which Blain called Ellis’ “brainchild,” arrived in 2019. The Democrat-majority Harris Commissioners Court passed it as part of a settlement.

“Initially, [it] was always supposed to be kind of focused on misdemeanor courts and letting out folks who shouldn’t be in jail because they couldn’t afford to pay.”

Since then the county has become infested with criminal activity, with law-abiding citizens in danger as judges release violent criminals.

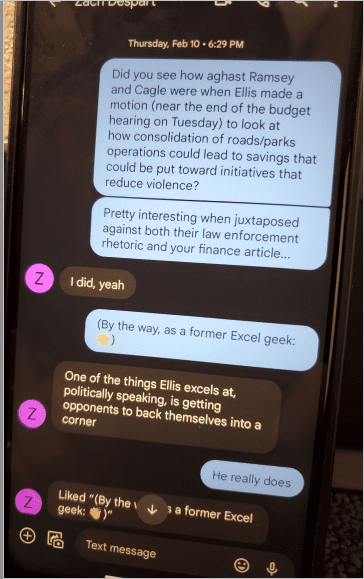

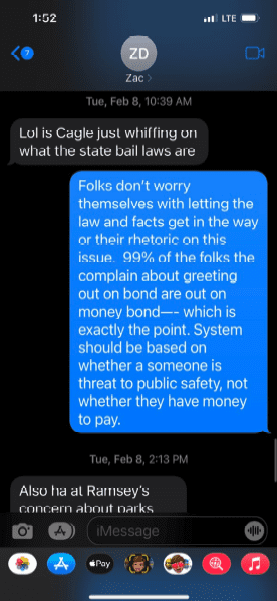

A Houston Chronicle reporter referred to it as a “crimedemic” in a text message exchange with Ellis’ staff.

Ellis’ web does include an internal ranking of power, and ranked second to the commissioner—not by much— is Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner. After him is fellow Democrat Commissioner Adrian Garcia. “With [those three] you have control over the county, and then you have influence over the city, because it is a strong mayor form of government. Whatever the mayor wants goes,” Blain said. He adds Turner is too powerful for Ellis to control, but they do work together. As such, Ellis and Turner are the only two shot callers in this spider’s web.

Indeed, this network involves many connections of people bouncing around multiple levels of government, and reaches all the way to the Texas Legislature through Harris County’s Democrat contingent. As such, it would likely take a voluminous amount of space to map the web in its entirety.

With all this going on, where is the major local watchdog?

Where is the Houston Chronicle?

They are the major legacy news entity in the area.

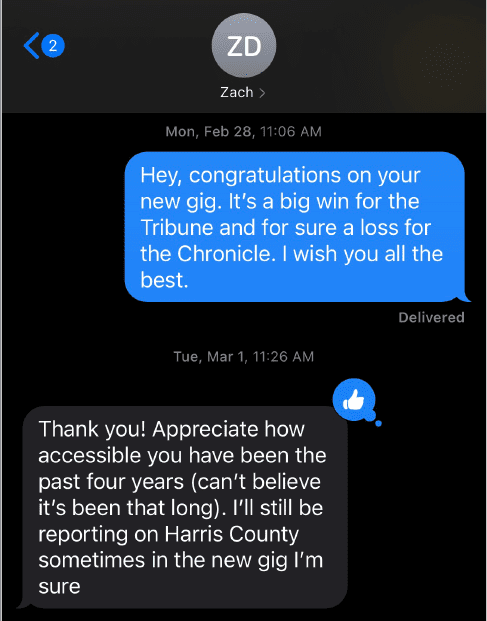

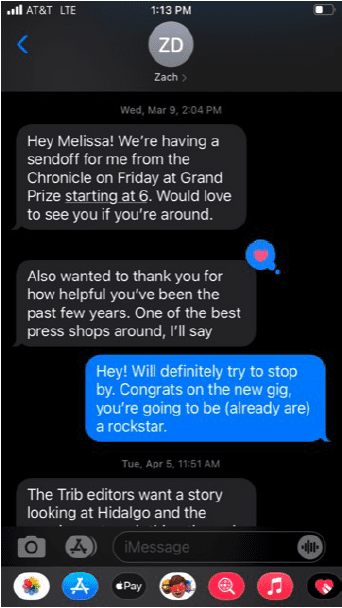

To their credit, in an exposé written this February by Zach Despart, the online newspaper reported on a “pay to play” system flowing taxpayer monies to those connected with commissioners’ donors. All commissioners, Democrat (including Ellis) and Republican, were criticized. Despart joined the Austin-based Texas Tribune shortly after the article was published.

Missing from the Chronicle’s expose were connections Texas Scorecard easily verified between Ellis and vendors who received contracts through other processes the Chronicle praised. The piece also held up the now scandal-plagued Hidalgo as a public servant exemplar.

That doesn’t mean the news publication and Ellis are opponents. Their editorial board recommended Ellis for election in 2020, and Commissioner Adrian Garcia (D) for re-election this year. Back in 1989, they also recommended Ellis for his then successful re-election bid to Houston City Council.

While reporting on Judge Cornelio’s recusal, the publication appeared to normalize the idea of judges receiving donations from attorneys who will later litigate before them in court.

Houston Chronicle recently took a swipe at the local Crime Stoppers chapter after those employed by it publicly pointed out the crime wave enveloping the area and calling out a local judge. Their Editorial Board launched another attack on May 3. On April 26, Commissioner Ellis applauded such attacks against the organization, and directed the Democrat-led commissioners court into blocking Commissioner Jack Cagle’s (R) effort to recognize a documentary Crime Stoppers co-produced. Ellis also called for investigations into the organization.

Current and past employees of the publication are aware of how incestuous things are in Harris County. “It’s a very small fish bowl of county, county officials, journalists … there are a lot of engaged tweeters… and they all talk to each other,” Houston Chronicle reporter St. John Barned-Smith told Texas Scorecard. The context of the conversation was accusations of bias at the Houston Chronicle.

We found fish food being directed at the news publication in this “fishbowl.” A search of the Harris County Auditor’s Vendor Payment Search Application showed taxpayer monies air dropped to Houston Chronicle from the county in two separate batches.

The Auditor explained to Texas Scorecard their vendor search portal, where citizens can learn how much of their money is getting paid to whom, only displays information as far back as February 2018.

The first drop of payments is to “The Houston Chronicle,” from February 2018 and ending in early 2020. Another tranche is addressed only to “Houston Chronicle,” also starting in February 2018 and ending March 7, 2022.

Altogether these payments total around $1 million. In response to our inquiry, the Harris County Auditor’s Office stated these payments are from multiple county departments, and countywide offices such as the county judge, commissioners, District Attorney, the Sheriff, and a Justice of the Peace. What these payments were for include categories such as public service announcements and “subscription services.”

For comparison, we scanned the City of Houston’s Controller’s website for city payments to the news publication. Reports there showed the city had paid them a little more than $3,300 from 2014 to 2016; nowhere near the amount from Harris County. No payments from the city were found after 2016, when Ellis was elected county commissioner.

Furthermore, in Ellis’ campaign finance reports from July 2016 and July 2018, we found his campaign paying monies to the Houston Chronicle; each listed as an “Advertising Expense.” Hidalgo’s campaign has also been paying the publication, as early as July 2018 and as late as January 2022, according to her campaign finance reports. The payments are described as for subscriptions and also, in July 2018, for “dues.”

Ellis and the Houston Chronicle are also linked by Kathryn Kase, a former Ellis employee and currently Judge Hidalgo’s legal counsel. She is married to Jeff Cohen, a former editor of the Houston Chronicle, who is currently employed by Arnold Ventures as a “senior advisor” in journalism. Kase did not respond to an inquiry from Texas Scorecard on this matter before publication.

Former Chronicle Deputy Opinion Editor Evan Mintz is also at Arnold Ventures, working as their communications manager.

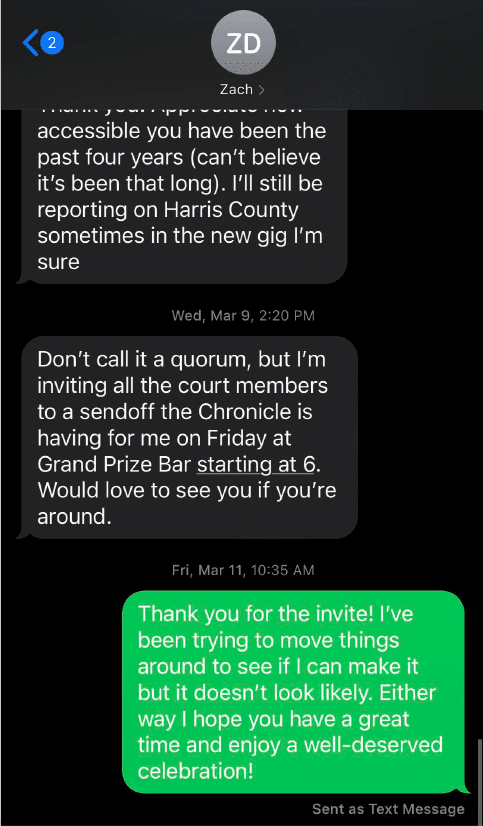

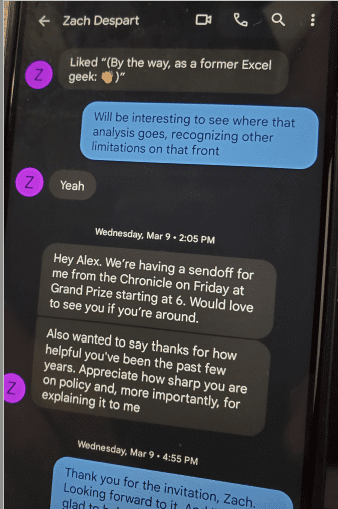

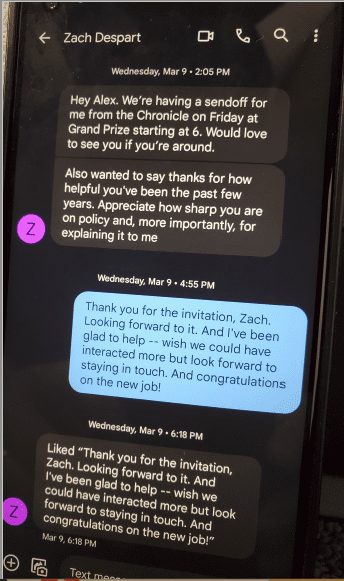

Through an open records request Texas Scorecard sent to Hidalgo and Ellis’ offices, we obtained the following text messages with Despart from this year.

The first batch of text messages are between Despart and “JLH” according to the filename. Judge Lina Hidalgo’s title, written in initials, would be “JLH.” Kathryn Kase, the judge’s legal counsel, would neither confirm nor deny these messages were between Despart and Hidalgo.

The next batch of text messages are between Despart and “AT.” The initials of Hidalgo’s indicted chief of staff, Alex Triantaphyllis, are “AT.” Kase would neither confirm nor deny these messages were with Triantaphyllis.

These messages discuss a fight between the Democrat majority and the Republican minority on the commissioners court.

Despart also invited “AT” to his going-away party and thanked him for “how helpful” he had been to him.

Despart thanked and invited another member of Hidalgo’s staff.

We also obtained communications between Despart and a member of Commissioner Ellis’ staff discussing Republican Commissioners Jack Cagle and Tom Ramsey.

Texas Scorecard contacted Despart to discuss these communications. “My employer’s policy prohibits my participation in your story,” he replied. He is currently with The Texas Tribune.

In response to allegations from a citizen, Barned-Smith strongly denied the Houston Chronicle is being “an active player” or showing “bias,” especially when it comes to his own reporting.

“Can we improve? 100 percent. Can we do a better job? 100 percent. Is it right for people to call us out on those issues? 100 percent,” he said. “I’ve covered Democrats, I’ve covered Republicans; I’ve taken whacks with my coverage, when it was necessary, at Democrats and Republicans.”

Ellis’ web touches the county, city, the Texas Legislature, and the Houston Chronicle. But there are other organizations linked to these spindles, as well.

Wait, There’s More

Ellis has sources of revenue outside of his public service as a commissioner. According to his most recent Personal Financial Statement, he has his own law firm, which was created back in 2002. He’s also employed by the law firm of Reaud, Morgan & Quinn.

His wife, Licia Green-Ellis, as previously reported, is a partner at the Waterman Steele Real Estate Consulting Group. Ellis’ PFR lists her as its “president.” She co-founded the group with Lance Gilliam and Tami Pearson in 2006, during Rodney Ellis’ time in the state Senate.

“There have been a lot of questions over the dealings of Waterman Steele, and the benefits that they’ve been able to receive because Licia Green-Ellis is a partner for the company,” Blain said. “The organization is dealing with a lot of property from the city, where this property goes through this program that allows it to be taken off of the tax rolls for affordable housing.” He explained many such properties have connections with Waterman Steele, and these actions decrease revenue to the city, county, and school district.

Outside the suspicious connection, such programs as these don’t even help lower the barrier to acquiring a roof over your head, according to James Quintero of the Texas Public Policy Foundation. “Government-run affordable housing programs don’t work because they ignore the root problem: government interference in the marketplace. In the instances where a select few benefit, the costs are just shifted to everyone else, who are left to bear any added burden,” he told Texas Scorecard. “The best way to go about getting a handle on this problem is to roll back local government tax and regulatory authority over the housing market and let the free market work.”

It appears Ellis has been plucking on his spider’s web to put in the fix instead of maximizing freedom.

In 2020, Urban Reform reported on a suspicious Waterman Steele-connected transaction: the Houston Housing Authority’s (HHA) had purchased contaminated land, ostensibly to build affordable housing. Licia-Green Ellis was found to be involved, as was Lance Gilliam (who has donated to Commissioner Ellis and Hidalgo).

Gilliam, a disgraced former chair of the HHA who left in 2014, was found to be a broker for the contaminated land.

Independent journalist Wayne Dolcefino reported 322 phone calls had taken place in one year between Licia Green-Ellis and HHA chair LaRence Snowden. Snowden dodged questions about Gilliam’s involvement.

Gilliam shows up elsewhere, too.

Texas Scorecard previously verified Ellis’ connection to the Coalition for the Homeless, which is chaired by Gilliam, and has received taxpayer monies from Harris County. A search of the Harris County Auditor’s Vendor Payment Search Application shows payments to Coalition of the Homeless and Coalition of the Homeless Houston, totaling more than $1.5 million since 2020. The Auditor’s Office provided documentation that most of these payments were for “emergency shelter,” and some for “rental assistance.”

Again, as the county auditor explained, their vendor search portal only displays information as far back as February 2018.

To their credit, Blain said local media outlets have reported on Waterman Steele.

Another organization with a tie to Ellis’ web network is BakerRipley. We previously verified a connection between them and Ellis, and how they have received county taxpayer monies. The Houston Chronicle reported it is one of the county’s top vendors.

Blain explained the significance of the nonprofit in Space City politics. “A lot of folks who either have worked for city, or county, have come through BakerRipley, or have done something with [them],” he said.

As previously reported, Hidalgo’s chief of staff, Alex Triantaphyllis, is a former BakerRipley employee. Additionally, Blain said City of Houston Attorney Arturo Michele, appointed by Mayor Turner, is married to BakerRipley’s new director.

A search of the Harris County Auditor’s search portal returned results showing a deluge of dollars directed at BakerRipley, totaling more than $119 million since 2019. The Auditor’s Office provided documentation that these payments were for “Rental Assistance,” and Hurricane Harvey Housing Rehabilitation.

There’s also Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston, which we reported has an indirect connection to Ellis. The Auditor’s search portal reports they’ve been paid more than $207 million since 2018. The Auditor’s Office provided documentation that these payments were for “Rental Assistance.”

“[Ellis’] network is used to advance his person, his policy positions and the things that he believes will make Harris County better,” Blain said. “But it’s also done for other things.”

Not all Democrats are supportive of Ellis’ web and what it has wrought.

Ellis’ Nemesis

In 2020, “priceless” African art was discovered in a county taxpayer-owned storage facility located in Ellis’ precinct. Questions swirled about who the owner of the art was, and why taxpayer monies were spent preparing the facility to store the art. And of all the county public servants listed as Democrats, only the District Attorney spoke out: Kim Ogg.

Blain noted she’s one of the few who will regularly challenge Ellis publicly. Ogg has fought with the Ellis-controlled commissioners court for funding to combat the crime wave, stating the Democrat majority has been “defunding” law enforcement.

Her investigation into Ellis’ art scandal found nothing, though she noted the situation was “problematic.” Blain said, “We still really don’t know who the proper owner of that African art is.”

That didn’t mean her quest to somehow hold Ellis accountable was over. It was reported her office that asked the Texas Rangers to investigate Hidalgo’s now indicted staff members. She also assembled the grand jury that issued the indictments.

Will Ellis’ Web Endure?

Since Ellis’ web network maximized its power, how have Harris County citizens’ lives changed?

“I think if you ask anybody, they’d say worse, particularly right now dealing with the crime issue,” Blain replied, noting how the commissioner encourages judges to release repeat violent offenders. He also points to Hidalgo’s and Ellis’ “reimagining of county government” scheme that has hiked the cost of living.

In this environment, threats have arisen to Ellis’ web.

If the scandals plaguing Judge Hidalgo weigh into the November general election, combined with midterm backlash to Democrats in D.C., there is a possibility she could be defeated by whoever wins the Republican primary runoff this May 24. Republican candidate Vidal Martinez currently faces questions surrounding prior donations to Hidalgo and other Democrats. He is opposed by Alexandra del Moral Mealer.

If citizens do give Republicans control of the commissioners court, it could snip Ellis off from the county judge’s office. That would limit, but not necessarily eliminate, his ability to influence the commissioners court, based on how things ran even when Republicans had a majority.

“He wasn’t always unsuccessful in his attempts at proposing something, getting them passed, he was just often unsuccessful with the things that the Republican majority did not like,” Blain said.

There’s another threat too. Outgoing State Sen. John Whitmire (D–Houston) has announced he’s running for mayor when Turner’s term ends in 2024. Blain believes Ellis and Turner will back former County Clerk Chris Hollins, who is working with Turner’s former campaign consultant. As county clerk, Hollins took broad liberties to overhaul the 2020 elections including 24-hour voting and drive-thru voting.

Reportedly, Whitmire and Ellis lately are opponents, not allies. Should he ultimately prevail and assuming Ellis is still in office a lost connection with the mayor would be a major cut into the commissioner’s web. And this wouldn’t be the first time Ellis went toe to toe with Whitmire. During his time on city council, it was widely reported Ellis wanted to “subpoena” Whitmire’s former sister-in-law, then-Mayor Kathy Whitmire.

In order for any lasting positive changes for lives and livelihoods in the county, citizens must activate and assert their self-governance at all levels of government, not just federal and state.

“I think that’s the only way that it’s gonna change,” Blain said.