Texas’ elected public servants and bureaucrats are continuing down a path of making energy in the state increasingly unreliable and unaffordable. The experience of roughly a hundred youths at a detention facility in North Texas during the February 2021 blackout casts a warning about this direction.

Throughout this series, Texas Scorecard has investigated the danger unreliable energy poses to the state’s electrical grid. Reportedly, through June of last year, 37 percent of total electrical generation in Texas came from unreliable wind and solar sources. Policies promoting these unreliable modes of production negatively affect electrical reliability and affordability for customers.

But it’s also a life or death issue. A 2021 article from The Guardian cautioned that extreme outside temperatures are a health threat for those who cannot maintain proper climate control in their residence. While the article is based on a study with a pro-unreliable energy bias, it affirms the importance of maintaining climate control in one’s own home and the threat power outages pose.

This would have remained a largely academic discussion were it not for the February 2021 winter blackout. That event affected real people and real lives. It showed how energy is not just a question of convenience but can quickly become a life or death issue.

Freezing Minors

It was the afternoon of February 16, 2021, during the winter blackout, and Judge Alex Kim (R) of the 323rd District Court in Tarrant County was alerted that trouble was brewing.

“Somebody from the community contacted me, saying there’s a power outage or there’s no heat at the juvenile detention center,” he told Texas Scorecard. “Just to do due diligence, I followed up and just inquired if all the power and electricity was working correctly as it should.”

First elected in 2018, Judge Kim has a track record of intervening and enforcing constitutional rights. In 2019, he stopped Cook Children’s Hospital’s attempt to suspend life-giving care to then 10-month-old Tinslee Lewis. She is still alive to this day, thanks to his intervention.

The tip to Judge Kim was proven correct. He emailed Bennie Medlin, the director and chief probation officer of Tarrant County Juvenile Services. “Are things in detention going ok?” he asked. “Has there been problems with water ([Fort Worth] water supply) or electricity (rolling blackouts or generators)?”

“The situation is not ideal in the detention center due to the numbers and [ongoing] power outages,” Medlin replied. “We have been experiencing rolling blackout[s].”

Texas Scorecard obtained these and other internal communications reported in this article through an open records request to Tarrant County.

But Judge Kim said this email exchange took place after his first attempt to learn what was happening. “When I first called up there, they told me everything was fine,” he told Texas Scorecard. “I believe when I contacted Mr. Medlin, he didn’t respond at the beginning. I had to follow up, and eventually he responded saying everything was fine.”

Medlin did not reply to Texas Scorecard’s request for comment on Judge Kim’s statement.

On February 17, CBS News ran a story reporting freezing temperatures at the Lynn W. Ross Juvenile Detention Center in Fort Worth. In the facility’s coldest room, an unnamed correctional officer claimed temperatures got as low as 27 degrees Fahrenheit. The article reported the facility, which had lost power that Sunday, housed 105 detained minors. Power was not restored until four days later.

Judge Kim explained to Texas Scorecard that there are four types of minors housed at this detention center at any given time, and not all of them are there for a crime.

Some of the minors are those with pending court cases who are not safe to release to the community. These can include children with mental health issues, capital murder suspects, those who have committed robbery, or those who are guilty of a felony and have been arrested for a new offense. The second group is minors who have been arrested but have yet to have a hearing before a judge to see if they are safe to release to the community.

The third group of minors is made up of runaways. Judge Kim explained that state law requires that juvenile children whose parents can’t be found must first be brought to a juvenile detention facility. “That’s where we keep runaway children until we can find the parent.” But sometimes, these children are running away from other states. In that case, there must be a hearing “to try and return the child to the state that’s requesting them.”

The fourth and final group is minors who have been found to have committed an offense and are awaiting placement. They can be placed in the Texas Juvenile Justice Department, which Judge Kim described as “more or less” a prison for kids. But, he added, some of these minors are waiting to be placed in rehabilitation.

Every child there is there because they’re either a danger to themselves, they’re dangerous to others, or there’s no place in the community that’s adequate to keep the child.

Judge Kim explained to Texas Scorecard why there should be public concern for the welfare of these minors. “Just because you’re accused of an offense doesn’t mean you did it, and everyone deserves the presumption of innocence. If some of these kids are truly innocent, then they shouldn’t be subjected to harsh conditions.” For those who have been found to have broken the law, he pointed to the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution:

Just because somebody broke the law doesn’t permit the government to subject somebody to unreasonable or inhumane conditions.

He also added that children don’t yet have the maturity to fully understand what they are doing and, for the most part, can be rehabilitated. “If our focus is on rehabilitating children, we need to do it as quick as we can, and we should do it as comfortably as [we] can, because any kind of negative adverse experience is only going to make the road to rehabilitation more difficult.”

Panic

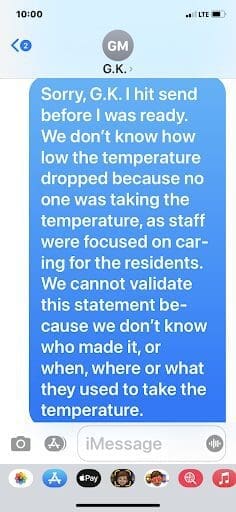

The CBS News article’s publication on February 20 got the attention of Tarrant County Administrator G.K. Maenius, who reports to the county judge (Glen Whitley, at the time) and the county commissioners. “Is it accurate that temperatures were 27 degrees in the facility as reported by CBS?” he asked Medlin in a text message.

Medlin accidentally sent a confusing reply before correcting himself.

“We don’t know how low the temperature dropped because no one was taking the temperature, as staff were focused on caring for the residents,” Medlin replied. “We cannot validate this statement because we don’t know who made it, or when, where, or what they used to take the temperature.”

Medlin’s texts from days earlier reveal even more about the size and scope of the problem caused by the statewide blackout.

“Detention has been running on generators since yesterday, and we found out today that the hot water heaters are electric and nit[sic] connected to the generators therefore we do not have hot water,” Medlin texted February 16 to someone identified only as Hope H. Among the email communications Texas Scorecard obtained was an email from a Hope H. Harris, Deputy Assistant Director for Tarrant County Juvenile Services.

Medlin also wrote about two heater units not being connected to the generators, as well as no power in the administration part of the building. Thus, like so many others at the time, it was cold and dark. “Can’t wait to get on the other side of this situation.”

Judge Kim apparently felt the situation was serious enough that, according to CBS News, he released nine minor inmates he believed were not a risk to the public or themselves.

Further communications revealed that not only did Medlin and the county have to deal with the fallout from the blackout, but also broken water mains.

On February 17, he requested an emergency delivery of bottled water from the Nestle corporation “due to the ongoing water outages.” On February 19, the Texas Juvenile Justice Department relayed a complaint, from a 16-year-old at the detention center. When he woke up, “the rooms were really cold and he was in the water. He’s been having flashbacks and no one is doing anything about it.” Jesus Reyes, deputy assistant director of Institutional and Education Services for Tarrant County, commented in the email chain that this was the same individual who refused a test for the Chinese coronavirus and “refused to leave his assigned room.”

Hygiene also became an issue at the Lynn W. Ross Detention Facility during the blackout. On February 20, an email from Judge Ruben Gonzalez indicated that toilets up to that time had been filled with feces, and had only just been cleaned. He also wrote that there was still a lack of water pressure. “We do not have a time estimate for complete operability because there are so many water main breaks in the area near the juvenile center,” he wrote. “The Fort Worth Water Department is actively seeking for the leaks to repair them and bring the system to full strength.”

Water Outages

Did the power outage also affect the water mains?

Texas Scorecard asked the Fort Worth Water Department. “It is difficult to say if the main breaks near the Lynn W. Ross Detention Center were related to the power outages,” replied Mary Gugliuzza, media relations & communications coordinator for Fort Worth Water. She broke down the series of events that led to the water outages.

Gugliuzza explained that Lake Worth is their “shallowest” water source, and because of that the temperatures fall faster there. Its water is treated by the North Holly and South Holly plants. “At the start of the winter event, the North Holly plant was out of service for maintenance. Fort Worth has five water treatment plants and 11 pressure planes. Through several booster pump stations, we have the ability to move water all around the city from the various treatment plants.”

Gugliuzza wrote that Fort Worth Water entered the February winter snap with a plan to “minimize” using water from Lake Worth. The plan was to only water water from the South Holly plant to service the Holly pressure plane—which includes the Lynn W. Ross Detention Center. Meanwhile, water from the Rolling Hills, Eagle Mountain and Westside treatment plants would supply the other pressure planes. “Water from the Holly plants routinely serves other pressure planes. We knew this would not eliminate an increase in main breaks, but we hoped to limit the areas impacted.”

This Gugliuzza said is where the power outages came in. “During the winter event, we lost power at the South Holly and Westside plants multiple times, and experienced an extended outage at the Eagle Mountain plant,” she wrote Texas Scorecard. “This forced us to bring the North Holly plant into service and push Lake Worth water to other pressure plans. The result was Fort Worth had 720 main breaks in 17 days (Feb. 11-27) with the big increase in breaks starting on Feb. 16.”

She added that cast iron lines break when water temperatures get to the low 40s. “There are over 800 miles of cast iron water lines in our water system. Water temp does not change as quickly as air temp so it takes a few days of below freezing temperatures before the impact is realized,” Gugliuzza wrote. “Fort Worth Water now has [a] goal to replace 20 miles of cast iron water lines a year. Even at this rate, it will take decades to eliminate cast iron water main from our system.”

Even with contractor crews ready to help water crews, and with the additional help of sewer crews, Gugliuzza said it wasn’t until the end of February that they got caught up on water main break repairs.

Final Reports

Three reports of the power outage at the detention center complete the terrible story. One is dated February 17, 2021 from Medlin to the Juvenile Board Review Committee Members, followed up by a March 4 update. The other was prepared by Deputy Assistant Director Jesus Reyes.

Medlin’s first report notes that the Juvenile Detention Center lost power “at approximately 2:00 am” on Monday, February 14, 2021. “There were 98 residents (12 Females/82 Males) in the center at the time of the outage.” While the backup generators turned on, “some of the center’s heating units and hot water boilers did not operate when the center lost power, and the telephone systems went down.” This, Medlin reported, blocked the center’s “ability to heat some of the housing units.” As part of their response efforts, staff handed out clothing, blankets, and coats.

The March 4 update provided more detail, stating “intermittent rolling power outages” began at 2:00 a.m., until 7:45 a.m. when the power went off “and did not come back on.”

Reyes’ report addresses the question of how power was lost to such a facility as part of the blackout. “According to Oncor, the facility is a critical facility; however, it is categorized with hotels and could not project when power would be restored.”

Judge Kim provided more information. “Oncor did not have the juvenile detention facility on their list of essential government buildings. So that would be like police stations, hospitals, fire stations, hospitals, jails, things like that,” he told Texas Scorecard. “When Oncor started doing the rolling blackouts because of the power grid failure, they just shut off the power to the detention facility. Eventually, when we got the county involved, the county made a call to Oncor to let them know that this was an essential building, and they restored the power.”

But it took time to get the power back on, leaving minors at the detention center freezing and staff struggling to respond.

Medlin’s report continues that Facilities Management was informed of the issues with the facility’s backup generators. At the time, it was believed the problems would be repaired that same day. They weren’t.

“As the day went on, we learned the heating and hot-water systems could not be repaired, and we still did not have power to the center. I advised the County Administrator and additional Facilities Management personnel of the situation, because temperatures in the center continued to drop.” Medlin’s March update added that the power outage affected “lighting, IT infrastructure, telephones, the facility HVAC system, facility surveillance cameras, hot water heaters, and laundry.”

Power was finally restored on Wednesday, February 17, 2021. But the problems weren’t over yet.

Medlin reports they discovered two water pipes had ruptured “on one of the boys housing units, and staff had to relocate the residents to other housing units to sleep.” His March update reported 16 residents were reassigned to other areas because of the major water leak.

“The reason why the pipes burst is because the electricity went out,” Judge Kim told Texas Scorecard. “When the electricity went out, it stopped the water pumps that circulate the water, and then you had stagnant water in the pipes, and then the pipes burst.” He pointed out that some of these pipes were in individual cells, some in the walls, and some in the hallways.

Records reported that Judge Kim released “approximately 8 youth to their parents” and transferred eight others to the Tarrant County Jail. “All HVAC system were fully restored and heating properly” in the afternoon of February 18, 2021. Two days later, all affected systems “were fully operational,” and water pressure fully returned to normal.

Despite the severity of these issues, Medlin reported that there had not been “major incidents or critical medical emergencies during this period.” Texas Scorecard asked Judge Kim what he heard about any medical injuries during this time.

“There were some injuries, but they weren’t permanent injuries. There were some cases of like frostbite, and some hypothermia,” he replied. “As soon as the county opened up for business, I went ahead and contacted all the attorneys for every child that was in detention, and required them to make contact and assess if they have any health issues.” He said all reported back to him within a week, and no lawsuits were filed as a result. “I believe there was a child or two that had to seek additional medical care when they got out for frostbite injuries, but I think the prognosis was okay. They made a full recovery.”

This sounds similar to a medical incident Texas Scorecard found among the communications obtained in response to our open records request.

In an email dated February 19, 2021, Dr. Donald Nelms of John Peter Smith Health Network in Fort Worth advised the county about “two male juveniles” being held at the Lynn W. Ross Detention Center. Dr. Nelms had examined photographs sent to him of the feet of these juveniles. According to the email, these feet were swollen for being in snow/ice “for an unknown time” on February 14. They had been arrested for robbing a 7-11 convenience store, and had arrived at the detention center the next day. Right when the power went, and with it the ability to keep the building heated.

The two males complained it hurt to stand up. “Photographs shows small amount of swelling, some edema to toe areas,” Dr. Nelms wrote. “Nurse relates they have good feeling in feet, vital signs stable, color of feet pink.” He advised they stay off their feet, their feet be elevated “when easy to do,” and not to use hot water because their pain sensitivity could be diminished.

Texas Scorecard sent an inquiry to Medlin about this incident. No response was received before publication.

Thankfully, according to the records reviewed, no one at the Lynn W. Ross Detention Center perished as a result of the power outage. While Judge Kim doesn’t believe anyone is responsible for the winter event, he does believe Bennie Medlin could have handled it differently. “He used his best judgment at the time. In hindsight, it’s easy to criticize somebody for their decision,” he said. “But looking back, I don’t think we should ever be afraid to go and ask for help from our government, from our elected officials. Especially if you are a branch of government yourself.”

Medlin did not respond to Texas Scorecard’s request for a response to Judge Kim’s statement before publication.

Stark Warning

Remember, this was a situation involving local government officials with some influence and resources, and they still had severe problems.

The effects of outages on citizens with limited resources can be far greater. Imagine such problems becoming more likely as Texas’ reliance on unreliable energy sources continues to grow at public servants’ behest.

Completely eliminating power outages is highly unlikely. But state lawmakers and bureaucrats can create an environment that decreases instability.

As dependent as the West is on electricity, it becomes a life or death issue when a loss of power robs a residence’s or facility’s ability to control its internal climate in extreme weather. It’s also a kitchen table issue, as the economy struggles and energy bills suck up more of individuals’ paychecks.

These are the stakes as Texas’ public servants and bureaucrats continue increasing unreliable energy generation as part of the state’s power grid.

No ads. No paywalls. No government grants. No corporate masters.

Just real news for real Texans.

Support Texas Scorecard to keep it that way!