A state agency with the power to kidnap kids and has exposed them to harm and subverted parental rights has a record of shoddy investigative work. Texas’ public servants have failed to hold the agency accountable.

A former investigator found a “statistically significant” number of the investigative findings of this agency have been overturned. These investigations involve the same individuals that forcibly take children from their families. Parents are crying out.

‘You’re Guilty Until You’re Proven Innocent’

“I don’t feel safe,” said Roland Ortiz, a 47-year-old resident of Cibolo, Texas. “The things that they can do to people, without knowledge, it’s scary.”

Ortiz, a father of three, is referring to his encounter with Child Protective Services (CPS), a branch of the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS). DFPS also supervises the state’s foster care system. Ortiz—whose kids are currently 6, 4, and 3 years old—claimed he was a victim of CPS incompetence, as his ex-wife tried weaponizing them against him in a custody battle in their divorce.

Ortiz said it started in January 2021, after his ex-wife filed for divorce. Just two weeks before, CPS came to his house.

“She made allegations that I had [committed] physical and sexual abuse on children,” he told Texas Scorecard. “Supposedly she had been speaking to CPS maybe … a month before she filed.” Ortiz also claimed his ex-wife admitted herself into a shelter, claiming she too had been physically abused, despite there being no evidence. “I think it was just a tactic. It’s just a malicious tactic that she used to try to incriminate me and try to keep my children away from me.”

Ortiz said CPS cleared him of the first wave of allegations his ex-wife made in 2021. But, in a theme that will seem familiar, CPS came back into his life in February 2022. Ortiz claimed his ex-wife had again alleged he had sexually abused his eldest son, who was 5 years old at the time. To protect his child’s identity, Texas Scorecard will use the pseudonym of “Jack” when referring to him. It was alleged Ortiz abused “Jack” in the bathroom of a facility where he had supervised visits with his kids. Ortiz at the time was under a protective order filed by his wife. “A couple of months later, they had come up with ‘reason to believe’ that I had done these things in that facility, without CPS even doing a thorough investigation of the facility where it supposedly happened,” Ortiz said. “They only came to my home, they interviewed me, and that was it.”

Regardless, if CPS’ findings against Ortiz stood, his ex-wife could use it to cut him off from his three children. “I never would have thought that anyone would actually come up with such horrific lies and grotesque allegations on someone you know,” he told Texas Scorecard. “I felt betrayed. I was depressed. … It was tough. It really was, especially with my boys.”

Ortiz hired an attorney and secured the services of Carrie Wilcoxson, a former CPS investigator and current child and family case consultant and advocate. Ortiz’ attorney requested a video CPS’ forensic interview with “Jack.” After viewing it, Ortiz said it looked like his son had been “coached” to confirm the allegations against him. He said the interview was done in April 2022, but he didn’t get a copy until roughly June 2022.

After reviewing Ortiz’ case, Wilcoxson advised him that CPS had bypassed a number of steps they were supposed to take before arriving at their conclusion. She told Texas Scorecard such behavior is not unusual for CPS investigators. “There are some really good supervisors [and] investigators out there that have done a good study of the policies that they’re governed by, and they know them. … But many more times, they don’t know what their policies are, they don’t know what their procedures are,” she said. “Then there are those instances where you have the investigator, or the caseworker, who has a good sense of their unchecked authority, and they’re acting as [such].”

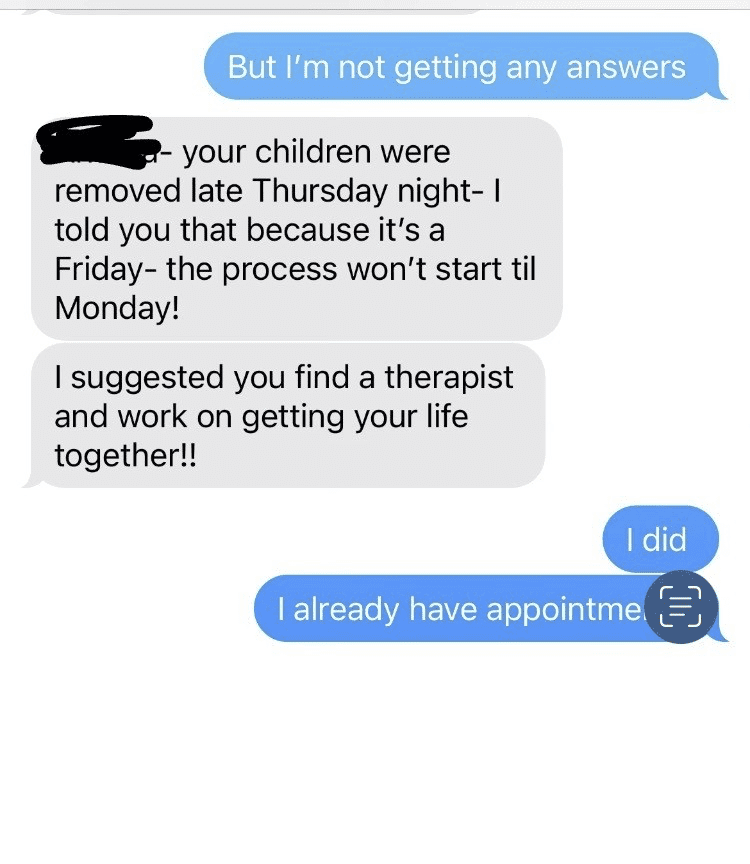

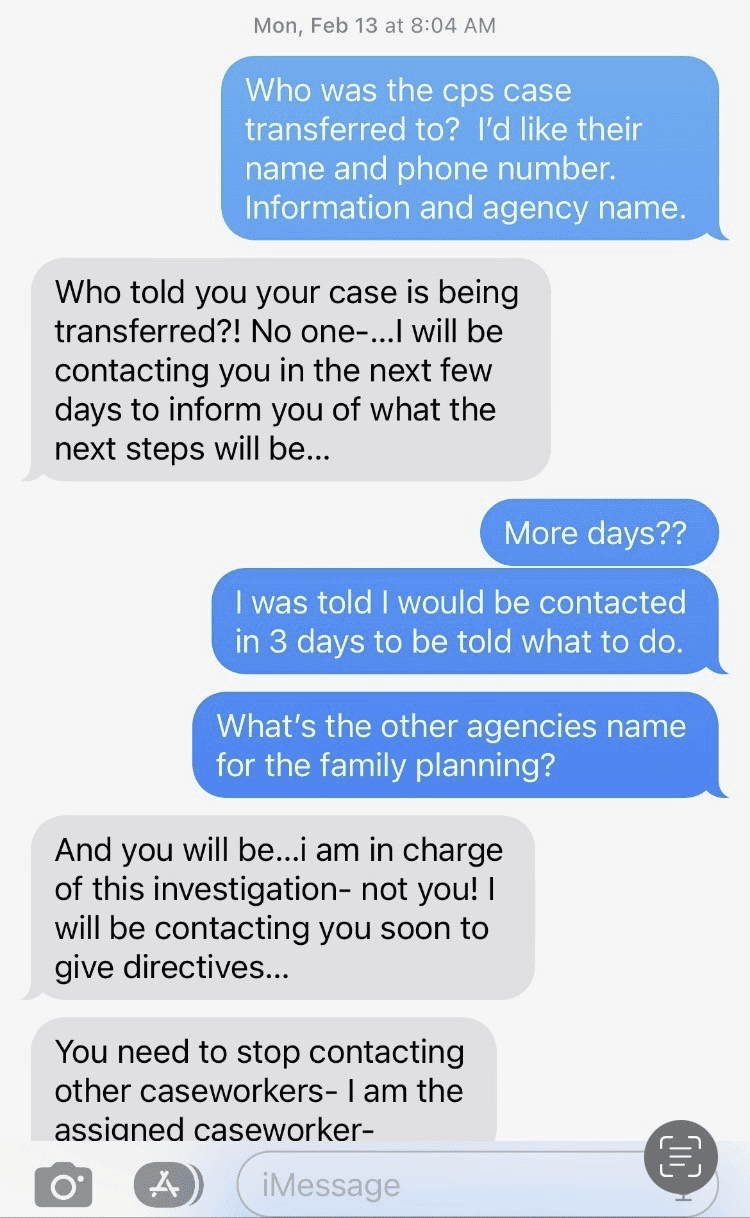

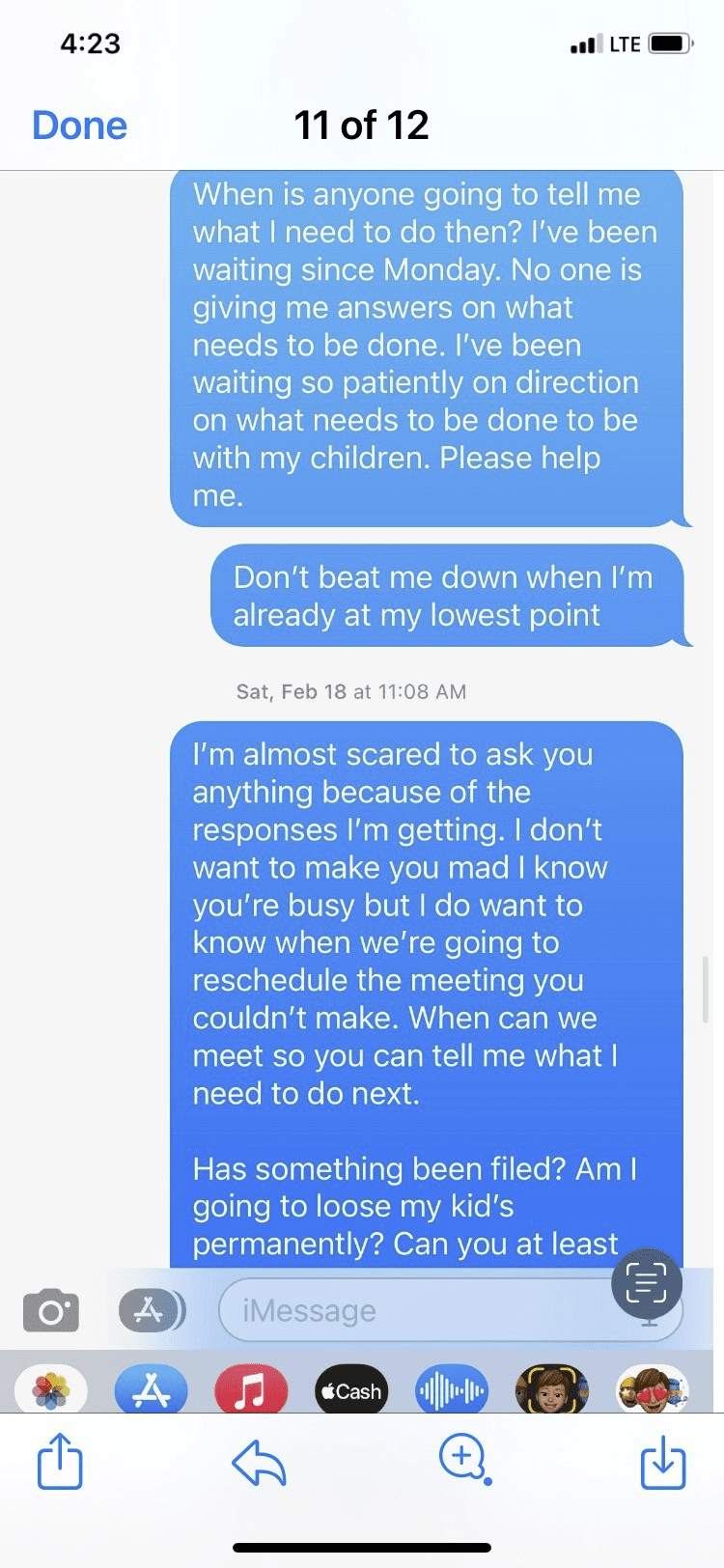

With the permission of another client, Wilcoxson shared screenshots of what she said was a text message exchange between a parent and a CPS investigator. At the request of the parent, the names have been withheld.

The unnamed parent had not seen his or her children for three weeks, and there was no signed safety plan as part of the process to restore the family. These involve agreements to participate in services, like counseling and therapy. There was only, Wilcoxson said, “a verbal agreement” between the parent and the state at this time. Wanting the restoration of the family, the parent, on their own accord, signed up for services. Wilcoxson said the following text message exchange is an example of CPS not following proper procedure. “[The safety plan] should [have] been developed together between department and parent[.] That is what the parent is trying to get answers on.”

The exchange also appears to be another example of DFPS subverting parental rights.

Source: Carrie Wilcoxson

Source: Carrie Wilcoxson

Source: Carrie Wilcoxson

“Because the investigator never responded[,] the parent then begins to contact the supervisor and the investigator tells her to stop doing that,” Wilcoxson wrote.

Texas Scorecard presented these screenshots to DFPS and requested comment. No response was received before publication.

Back to Ortiz’ situation: Wilcoxson told him they only had a window of time to file for an administrative review of CPS’ findings against him. They filed for the hearing, which happened in September 2022. “We had that hearing and all the dispositions were reversed,” Ortiz told Texas Scorecard. “Every single one of them was ruled out.”

He provided a copy of an email from Tanya Netardus at DFPS, dated September 19, 2022. Texas Scorecard redacted the names of Ortiz’ children and other personal information from this document. This email stated that CPS’ findings of there being a “Reason to Believe” allegations of physical and sexual abuse were reversed. All allegations against Ortiz were changed to “Ruled Out” as a result of the review.

It’s also alleged that the CPS investigator may have broken the law in the 2022 investigation of Ortiz. State law that came into effect September 2021 states CPS investigators are required to inform those whom they are investigating—verbally and in writing—of their right to record. Texas Scorecard asked Ortiz if he was informed, and he said he was not.

Texas Scorecard sent a copy of the September 19, 2022, email to DFPS, requesting comment and confirmation of its authenticity. We also asked about Ortiz’ claim he was not notified of his right to record by CPS when investigated. “CPI and CPS cases are confidential according to state law so, while I’m not able to comment on these specific cases, I can confirm all investigators are trained to explain to each alleged perpetrator what their rights are – including the right to record,” replied Marissa Gonzales, media relations director for DFPS.

For Ortiz, after working with Wilcoxson, he believes CPS’ actions weren’t malicious. Rather, they’re jumping the gun and bypassing proper procedures is evidence of a lack of training. “I think what they need to do is they need to do things a little better, and hire people, and train them,” he said. “Things like this, you’re guilty until you’re proven innocent, and that’s awful.”

Winning this fight cost Ortiz dearly. He claims to have spent more than $150,000 defending his parental rights, and to clear his name. “I lost my business, I lost the ranch, I lost all my possessions,” he told Texas Scorecard, “That’s okay. It’s not about that. It was about my children mainly.”

He’s still having to fight. While he’s managed to start another business, Ortiz claims his ex-wife is still trying to weaponize CPS against him. He still has Wilcoxson to help him, and this time CPS seems to be following procedure with him now, rather than jumping to conclusions.

Ortiz’s story of shoddy investigative work isn’t an isolated one. There’s more, and finding that out started with the original subject of Texas Scorecard’s investigation into DFPS. That subject’s name showed up in the email noting the findings against Ortiz were reversed: former DFPS Commissioner Jaime Masters.

Backstory

Masters was fired by Gov. Greg Abbott on November 28, 2022. This was six days after Texas Scorecard published an investigative report revealing how the state agency rebelled against public servants’ efforts to protect children from gender mutilation and hormone manipulation.

This wasn’t the first time DFPS was caught abusing their power.

The agency kidnapped 4-year-old Drake Pardo from his parents in 2019, a move later found to be illegal and unjustified, by the Texas Supreme Court. Drake’s parents were finally removed from DFPS’ Child Offender Registry in December 2021.

Considering DFPS’ far reach, Texas Scorecard launched an investigation to determine why Masters was fired. Did she fail at reforming the agency? Or was she reforming a little too well? Texas Scorecard obtained records from the Office of the Governor (OOG) that showed Masters and Abbott’s staff pointing fingers at each other. Masters’ complained Abbott’s staff had turned DFPS into a hostile work environment, but the OOG’s internal investigative report said there was no substance to these allegations, and multiple members of Abbott’s staff expressed state lawmakers had lost faith in Masters.

Texas Scorecard then sent open records requests to the only two state lawmakers explicitly named in those records: State Rep. James Frank (R–Wichita Falls), and State Sen. Charles Perry (R–Lubbock). Open records requests were sent to both. Records from Frank highlighted an August 2022 Fox 26 Houston report of a Child Protective Services (CPS) staffer encouraging an underage girl in CPS care to engage in prostitution.

Not properly caring for kids seems to be the norm, not an exception, for DFPS. It has been widely reported that children in CPS care have been exposed to risk. This problem escalated to the point that a federal judge—Judge Janis Jack—has the state agency under a microscope.

Sifting through government records to determine what the truth is about Masters firing is much like the Sherlock Holmes’ adventure, “The Dancing Men.” In that story, a couple is harassed by drawings of dancing men painted on their property. Holmes deduces the drawings are coded messages, and the only way to fully decipher the language is by collecting more messages.

So too in this case, the more records that are examined, the less mysterious this matter becomes.

The records received from Frank’s office were analyzed in our previous article.

What did a review of Sen. Perry’s records reveal?

‘We Are Wrecking Families’

DFPS allegedly is breaking state law, and testimony to state senators points to data indicating an unacceptable level of shoddiness in CPS investigations.

Perry’s office turned over multiple records to Texas Scorecard, including a bombshell December 2022 Final Report from the Texas Senate Special Committee on Child Protective Services. It was commissioned in the 87th Legislative Session in 2021 by Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick (R). State Sen. Lois Kolkhorst (R–Brenham) was committee chair, and Perry served as a member. This report exposed major issues within the Department of Family and Protective Services, which again is the parent organization of CPS.

Texas Scorecard asked both Kolkhorst and Perry for comment on former DFPS Commissioner Jaime Masters, and the December 2022 Final Report. No response was received before publication.

Included in the Final Report is written testimony, dated May 3, 2022, from Carrie Wilcoxson. In her testimony, Wilcoxson reveals what she found after studying ten years worth of DFPS Administrative Review of Investigative Findings (ARIF) data. Roland Ortiz, mentioned earlier, on Wilcoxon’s advice filed for an ARIF, which resulted in CPS’ findings against him being reversed. “Investigations is very important, because that’s the front end of where everything begins,” Wilcoxson wrote Texas Scorecard.

“It’s not like it’s a different type of workforce that does removals. If their work on just case findings [are] overturn[ed], then how many get by over to legal removals [of children]?” She also explained the Administrative Review process. “It is informal, you don’t need an attorney to do it. A parent can do that on their own. I wouldn’t really recommend that necessarily,” she said. After the parent requests it, and it is granted, the review is assigned to a “resolution specialist” outside of the area where the original CPS investigation was conducted. The parents, or their attorney, then present their argument for why CPS’ finding should be overturned.

Wilcoxson looked at data of DFPS ARIFs from 2010 to 2020. She testified to state senators that she found a “statistically significant error rate” of CPS Investigative Findings. She said the individuals involved in these investigations are “the same workforce and workmanship … used to effect child removals.” In other words, these are the same people who can take your children from you.

There are two levels when parents file for an ARIF, and the numbers Wilcoxson presented to state senators are shocking. She said at level one, “an average of 32.2%” of CPS Investigative Findings were overturned, and at level two, “an average of 30%” were overturned. “So we might be able to state over 50% of the CPS Investigative Findings are overturned,” Wilcoxson told senators. She wanted to know how many of the “requested appeals in [the] second level” were those not overturned from the first level. If those in the second level were carryovers from unreversed ones in the first, Wilcoxson told senators “the error rate is closer to 50 percent.”

Source: Texas Senate Special Committee On Child Protective Services

She told Texas Scorecard that her findings are consistent with her experience. She has been handling ARIFs since 2010. According to her, reversals at the ARIF level are due to poor investigative practices on the part of CPS. “Oftentimes, believe it or not, these CPS findings are overturned because … I’m able to say to the resolution specialist, ‘these eyewitnesses were available on day one, and this investigator never even made contact with them,’” Wilcoxson explained. “Had they made contact with them, they will have learned that the allegations were absolutely not possible, or erroneous, or false, or whatever the case may be.”

Wilcoxson said she emailed Commissioner Masters about the ARIF data and offered “to discuss and review” it with her. “That was her first year I sent her an email. I said, ‘Hey here’s the data. If you want to sit down and meet, let’s do so,” she told Texas Scorecard. “I never got anything back from her.”

Wilcoxson believes there could be a connection between this shoddy investigative work, and DFPS’ capacity problem in the state’s foster care system. “You might have a foster care capacity because you might have children in care that don’t need to be there,” she said. It has been widely reported that a federal judge has DFPS under a microscope for exposing children in their care to risk, including not having a place to house them. That is referred to as Children Without Placement (CWOP).

In the Senate Committee Report, Wilcoxson asked senators the one question every wronged and unheard parent, who has encountered CPS, likely asks every day. “How can a parent who is later reunified seek sanctions for harm of their child while in foster care?”

Wilcoxson emphasized to state senators the severity of this issue and what it means. “What is the department doing to address the statistically significant error rate of their Investigation Findings in where the same workforce and workmanship is used to effect child removals?” she testified. “Until folks understand this and care, we are wrecking families and potentially placing anywhere from 5,500 to 10,200 children in care wrongfully each year. That is huge!”

Texas Scorecard asked DFPS to comment on Wilcoxson’s testimony. “The numbers are valid, however, I will note that the statistics aren’t linked to removals – they’re the numbers for all reviews, not specific to cases that that resulted in a removal of a child,” replied Marissa Gonzalez of DFPS. We followed up by asking Gonzalez what this statistic says about the quality of DFPS’ investigative work, and what faith Texans can have that every time a child is kidnapped from his parents, it is justified and not a result of shoddy CPS work. No response was received before publication.

We asked Wilcoxson if Texas is still trending in the direction seen in the 2010-2020 ARIF data. “I would say we’re still trending,” she replied, basing it on her own experience as a consultant. “I would say a majority of my cases, as a business owner, are the overreach of authority cases. And I would say that probably 10 percent, maybe 20 percent of my caseload involve families and parents that are demonstrating a need for intervention services.”

Texas Scorecard also asked Krista McIntire, a CPS consultant and parent advocate, if DFPS is still subverting parental rights and kidnapping kids since the Pardo situation in 2019. “Since the 2019 Pardo Family tragedy, many legislators suddenly became aware of what is happening to their constituents. Thankfully, reformative legislation [was] successfully passed following the well-known case. We saw a drastic decline in families in Family Based Safety Services and unlawful removals.” she replied. “Although advocates were hopeful of the reform, the department quickly started to utilize their ability to have ex parte hearings to forcibly make parents participate in an investigation without probable cause, a violation of the constitution. An ex parte hearing is one in which one party is not permitted to be in the court—that party being the family.”

McIntire has also noticed CPS’ investigative incompetence. “Investigations lack many constitutional rights and basic due process. If one values the constitution, then it’s a no-brainer [that] this is the biggest issue and will remain as such,” she said. “A rapist has more rights than a parent who is accused of leaving their child outside without a jacket on.”

But there’s also a concern that not enough affected parents have availed themselves of the critical administrative reviews Wilcoxson mentioned. “The 10 years of data, I think the highest that’s ever taken advantage in one particular year was something like 1,100 or 1,200. The average, I think, is about 900 per year,” she told Texas Scorecard. “But when we look at the number of eligible individuals, that’s tens of thousands of people statewide.” She added this is why she worked with state lawmakers and wrote proposed legislation that became law, mandating that DFPS notify—verbally and in writing—parents of the appeals process, as well as their right to record conversations with CPS investigators.

Texas Scorecard asked DFPS why so few Texas families avail themselves of the informal review process. No response was received before publication.

Wilcoxson raised the question if DFPS is rebelling against these requirements. “Are they implementing new state laws on notifications of the right to record and write to appeal both verbally and written? If so, do the number of written forms that they have obtained match the number of investigation interviews?” she asked senators. “As a consultant on these cases throughout the state, I can tell you that this is not happening.”

Ortiz claims that at no point did CPS ever inform him of his right to record the investigator when he was approached in 2022. Another family also claims that CPS broke this state law, and that they too are victims of DFPS’ tyranny.

Traumatizing Families

“You’re claiming mental and emotional abuse. [But] what are you doing? You are mentally and emotionally abusing, traumatizing families daily.”

Cama Niccum told Texas Scorecard this while discussing her experience with CPS. Cama and her husband, Robby Lerille, are married with five children. They lived in Pampa, Texas, a small town roughly an hour from Amarillo. Small towns can seem quite peaceful and serene, but for Cama and Robby, it contains heartbreaking memories. Here is where it all started. Here is where they’d encounter CPS, and events would unfold to where all but one of their kids would be kidnapped from them.

CPS entered their lives in March 2021. They came after Cama and Robby engaged in physical correction of their eldest kid—nine at the time—who has ADHD. To protect her identity, Texas Scorecard is assigning this child the pseudonym of “Jane.” Their second oldest, at six years old, will be called, “Jill.” “[‘Jane’] requires a little bit more stern, firm discipline,” Cama told Texas Scorecard. She said, “Jane” over-exaggerated pain in her shoulder while at school. When a teacher asked to look at it, she noticed what Cama called a “very faint bruise.” She explained where the bruise came from. “At that time, we were spanking whenever she needed it … she was fighting this, and she fell and hit her little shoulder on like a toy or something on the floor.”

That triggered a call to CPS. Caseworker Laurie Martinez came and pulled Cama and Robby’s two oldest kids—”Jane” and “Jill”—out of school and brought them to a child advocacy center called “The Bridge” in Amarillo. Why did Martinez do this? Because of allegations of mental and emotional abuse committed against their eldest child when they physically corrected her. At “The Bridge,” the children were evaluated and questioned.

Eventually, CPS returned the children, though Cama said they didn’t have “Jill” in a booster seat when they brought her back. “You’re hollering ‘best interest of the child,’ and you don’t even have my 6-year-old properly restrained in the vehicle, in a booster seat like she should be.” But CPS didn’t just bring the children. A law enforcement officer came too. Cama said he threatened that they have “Jane,” the one they corrected, placed with a relative. Cama and Robby complied. “We were dumb, we were naive,” she said. First, they placed “Jane” with Cama’s grandparents, but Cama said they were too old to handle a child so rambunctious. Later, “Jane” was placed with Cama’s own parents.

Eventually, this case was closed, and the family could reunite. But CPS never told Cama and Robby this. They didn’t find out until June 2021, three months later, when they called CPS. They were told the case was closed in May. “I never got a letter, and never gotten nothing saying that the case was closed,” Cama said. “My daughter has been in the care of my parents for a month, and this case has been closed.”

This sounds familiar to someone else who’s encountered CPS. Tina Freeman worked in the Caldwell County District Attorney’s office for 10 years, and then was elected several times as district clerk. She was the one who reached out to Texas Scorecard and connected us with Cama and Robby. She’s been advising both of them ever since learning about their case.

Tina claims her family too has been a victim of CPS bad actions. She personally encountered CPS because of her son-in-law’s drug issues. There was also a charge of domestic violence, which Tina said was later dismissed. Regardless, her daughter and grandkids came to live with her during her son-in-law’s problem. That’s when CPS paid a visit to Tina’s house, wanting an interview. Tina claims the CPS investigator told her daughter to get drug tested as well. “She goes and drug tests that next Monday. [The CPS Investigator] said normally it takes so many days, and you’re good,” Tina told Texas Scorecard. “He never contacted us never. They leave families in limbo.”

This brings up a point Tina wanted to highlight: “When they call you, you better answer. But if you need them, they’re nowhere to be found if there’s an issue.”

At least for Cama and Robby, they got a happy ending, right? Their family was reunited. Both parents, after this encounter, decided to abandon physically correcting “Jane.” Instead, they resorted to methods like time out or taking away privileges.

And CPS, the arm of the Department of Family and Protective Services, never entered their lives again, right?

Wrong. Cama and Robby claim their nightmare was only just beginning.

The Return

It was February 2022, roughly nine months after Cama and Robby’s first encounter with CPS. All seemed well, only for it to suddenly change.

“Jane,” the one with ADHD, like all kids, doesn’t like to do homework. One day, Cama said “Jane” resisted so strongly that eventually, Cama sent her to her room. A reasonable action most parents might understand, and “Jane’s” reaction is one more than a few parents have likely also experienced. “She stomped off to her room and slammed the door, and she starts throwing a fit. I mean, it’s kicking [and] screaming in her bedroom,” Cama recalled. In response, she said she told “Jane” that she was going to stand in timeout. “She does not like authority. She starts screaming at the top of her lungs.”

What followed would be the first link in a chain of events that brought back CPS. “I was trying to talk to [‘Jane’], and I couldn’t because she was screaming at the top of her lungs,” Cama recalled. “I just kind of jerked her ponytail, like just to get her attention.”

Roughly two weeks later, again at public school, “Jane” talked. “She made an outcry to this teacher’s aide that her mom dragged around by the hair of her head and slapped her in the face at home,” Cama said. “So, same situation. The teacher reports it, and that’s how a CPS caseworker showed up at our door.” This one was named Leitha (Miki) Little.

Since last time, Cama and Robby had done their own research of state law about their rights. Now, CPS wasn’t coming to two uninformed people, but to two empowered citizens. “We were naive. We just thought, okay, let’s get this done and over with, and they’ll be gone out of our lives,” Cama said. “The second go around when she showed up, I invoked my rights, and I refuse to talk to her.”

Seems like a sound move. Most attorneys advise you not to talk to the police when being investigated. It’s not because all cops are bad or incompetent. Even the best ones can make a mistake and arrest an innocent person, sincerely believing he or she is guilty. Because of the fallibility of human beings, in the United States, we believe in the phrase of “innocent until proven guilty in a court of law.” The normal response when a citizen invokes his or her rights should be for an investigator to then continue their investigation by other means. Afterwards, evaluate if there is enough evidence to warrant further action.

Did CPS do this? Not at all, according to Cama. Instead, Little went to DEFCON 1 and got a court order for a motion to force Cama to participate in court-ordered services. Cama called her husband, Robby, and he contacted Little. He told her he wouldn’t let her in the house, but agreed to bring his children outside so that Little could see for herself their kids weren’t being abused.

Neither Cama nor Robby said at any time did Little follow state law and inform them of their right to record her. This is consistent with Roland Ortiz’ claim he wasn’t told, and with Carrie Wilcoxson’s testimony to the Texas Senate Committee.

Robby said that, during their roughly hour-and-a-half conversation, he told Little that his wife didn’t want to talk to her because of their previous interaction with CPS. “I kept asking her, ‘do you think my kids are in any type of imminent danger? You think they’re unsafe?’ She told me ‘no,’ she says, ‘I just want to make it so CPS doesn’t have to get involved in y’alls lives ever again,’” Robby told Texas Scorecard. “She left … and that’s when they filed the affidavit with the courts to get an order to participate.” Robby clarified this order was targeting only his wife, not him. But he also didn’t escape Investigator Little’s accusatory finger. “In her affidavit, she states that me and Cama were both uncooperative through the whole thing.”

Roughly two years after public servants oppressed citizens with mask mandates, Cama had to go to a court hearing over Little’s request she be mandated to participate in services like anger management, psychological evaluations, and such. Robby described what happened during that hearing. He said CPS’ attorney asked Little what were the allegations against Cama, and that she responded, ‘treating the kids differently.’”

“There was a long pause. The judge intervened and asked her ‘that’s it?’’ Robby recalled. “She said, ‘oh and physical abuse.’ But they never said what the physical abuse was or the emotional abuse.” Judge Jack Graham, presiding over this case, granted CPS’ requests. “They told Cama [to] take a psychological evaluation, anger management, parenting classes, and she had to sign a release for all her medical records.”

For Robby, this was a moment that shattered his trust. “I have lost full faith in the court system after that,” he said. “I’ve seen criminal cases that they get more protected rights then she did there.”

Judges not doing their jobs was a theme in the Senate Committee December 2022 report too. “How are we ensuring the judicial level is also not making such mistakes and permitting child removals wrongfully[,] perhaps through practices of giving deference to the department over evidential standards?” Wilcoxson testified to senators. “Why isn’t the department being sanctioned within the judicial process when infractions are identified?”

Former Harris County Associate Judge Paula Vlahakos raised this issue to state senators as well. She recommended “increased training for judges presiding over child welfare cases and for the lawyers who represent parents and children in those cases.” She said this should be done “to ensure all parties apply the basic tenets of civil procedure,” adding that “when everyone applies the same rules, consistency in case outcomes can improve while ensuring due process.”

Robby and Cama kept on fighting. Recall the internal DFPS data Carrie Wilcoxson testified to state senators about? She said, if you include data from both appeal levels, roughly half of CPS investigative findings from 2010 to 2020 were overturned. Wilcoxson emphasized the individuals conducting these investigations are the same ones involved in child removals. Cama decided to appeal for an ARIF herself. The result was consistent with Wilcoxson’s testimony to state senators. “They actually overruled that decision. Emotional and mental abuse was ruled out,” Cama said. “And then physical abuse was unable to determine.”

Cama provided a copy of what appears to be DFPS’ Administrative Review of Investigative Findings (ARIF) of her case, dated July 11, 2022. The review was requested on May 9. Texas Scorecard has reviewed the document, and asked DFPS for comment and to confirm its authenticity. Marissa Gonzalez of DFPS replied that she couldn’t comment because “CPI and CPS cases are confidential according to state law.” The names of Cama and Robby’s children have been redacted, as well as personal information.

The review, conducted by Robin Arnold, resulted in, again, CPS’ investigative findings being reversed. Also, nowhere in Arnold’s review of the CPS Investigator’s report was there any indication Cama and Robby were informed of their right to record when approached in 2022. This is required in state law as of September 2021. As noted earlier, Marissa Gonzalez of DFPS said “I can confirm all investigators are trained to explain to each alleged perpetrator what their rights are – including the right to record.”

Originally, on the allegation of emotional and verbal abuse of “Jane,” CPS said there was “Reason to Believe,” and categorized it as “Serious.” After the review, just as Cama said, this allegation was changed to “Ruled Out.” An allegation of physical abuse remained “Unable to Determine.”

Among the materials, Arnold used to conduct her ARIF was a copy of an evaluation of “Jane” by a child psychologist, Dr. Steven Schneider. He gave a diagnosis that this child does, as Cama stated, have ADHD.

Arnold also reviewed a March 8, 2022 interview with “Jane.” In it, she recalled when Cama “tugged her hair slightly,” and that “it was not hard and did not hurt her.” She also said her mother accidentally scratched her, and that the act was not meant as punishment. “Jane” said when she started “acting up again,” Cama restricted her iPad use to one hour. “Jane” said that she herself “throws a lot of fits, and that is the reason why she was in trouble.”

“Jane” categorically stated, “no one has ever hurt her,” and was “maybe 1 or 2 percent scared of her mother.” She expressed concern Cama “might lose her anger one day and just do something not right,” but “doubts that would happen.”

The types of discipline “Jane” described being given are being told to go to her room, or sit in a corner, sit on the wall, or write sentences. She also mentioned that her own anger will result in not being allowed “to go outside and play.” “Jane” added that Cama “controls her anger by yelling and walking away.” One incident, that took place the day of the interview was over school work, and “Jane” alleged Cama told her to walk home.

Cama’s parents, Shelia and Ronnie Niccum, and her sister Caragan, alleged abuse of “Jane” while being interviewed with CPS. Cama claims that she’s “never really had a very good relationship” with her parents. “They’ve always tried to implement themselves into our lives when it comes to how we raise and discipline our kids! They’re all about control, always have been even when I was little and growing up,” Cama told Texas Scorecard. “They told CPS all of that stuff is because they don’t agree with our methods of discipline, and … because me and my parents have never really had a very good relationship.” Roland Ortiz, at the beginning of this article, claimed his wife tried to weaponize CPS against him.

Regardless, in the ARIF, Arnold wrote that “there does not appear to be a preponderance of the evidence that supports” the original CPS finding of “reason to believe” mental and emotional abuse was committed.

“There is insufficient evidence that [redacted] experienced significant or serious negative effects on her intellectual or psychological development or functioning,” the ARIF stated. “There is no information within [redacted]’s statement and/or statements from professional collaterals that [redacted] suffered an observable and material impairment.”

Arnold did add that this finding “by no means … negate the fact that risk was identified by the investigator and services were recommended for this family. This Administrative Review decision does not alter or terminate any services recommended by the Department.”

Cama still had to follow Judge Graham’s mandate, and they still had more court hearings to go to as the process against their parental rights continued to grind. Cama and Robby say they don’t have the income to afford attorneys of their own, so they’ve only ever been able to rely on court-appointed attorneys. And for whatever reason, Cama said her attorney never brought up DFPS’ administrative review in court. “I still do not think that my administrative review has been reviewed.”

This was another problem Tina Freeman claims to have noticed. She said before the Texas Legislature passed House Bill 567, those CPS investigated, if they couldn’t afford attorneys, none would be appointed to represent them. CPS would have their attorney, and you’d have to figure it out for yourself. But even after the changes HB 567 brought, Tina, says all still is not well. “Fast forward to people now getting attorneys, a lot of times, their attorneys are appointed, and they’re not doing anything,” she said. “I hear this over and over again: they don’t do anything, they won’t talk to me, they’re not prepared.”

The Kidnapping

By this time, Cama was pregnant again. She didn’t want her newest baby born in Texas, where the claws of CPS could reach into their family. So in August 2022, Robby and Cama started moving the family to Louisiana. On August 31, there was an ex parte hearing, and the court declared their children were in immediate danger. “They still have not said or told us what the immediate danger is or was,” Cama said. Up to this time, Cama was the only one named in any court orders. Now, all four of their kids, minus the one Cama was pregnant with, and Robby were named in protective orders for the children. Then, a month later, Cama said Judge Graham told her to take their kids to a sheriff’s office in Louisiana. Robby, based on his lost faith in the justice system and how he saw Judge Graham handle their case, refused. “The bias that he was showing was just unbelievable, and there was no way in —- I was gonna let my kids go back anywhere near this system,” Robby told Texas Scorecard.

That’s when these parents claim “the system” cracked down. In November 2022, while in Louisiana, law enforcement pulled Cama and Robby over. They arrested Cama for the charge of interfering with child custody. Robby said he wasn’t arrested but was detained in a room for four and a half hours. Meanwhile, law enforcement showed up at Robby’s mother’s house in Louisiana, where their kids were. The kids were taken all the way to a foster home in Lubbock, Texas.

After roughly 30 days of her arrest, a pregnant Cama, still sitting in a Louisiana jail, was picked up by Texas law enforcement and taken back to Pampa, over 700 miles. Robby followed and went through a bail bondsman in order to pay for her $250,000 bond.

That brings us to today. Cama isn’t behind bars. But their family isn’t whole.

Cama and Robby have their newborn baby in Louisiana, but not the rest of their children. They’re all still in Texas. They were in foster care from November to December 20202, when a week before Christmas, the kids were brought to Cama’s parents, the very ones who alleged to CPS “Jane” was being abused. They’re still there as Robby and Cama continue going through permanency hearings in the court of Judge Graham. “The kids are thinking that we willingly gave them away or something like that,” Robby said while crying. “My 4-year-old, she’s asking questions like, ‘What, Dad, you don’t love us anymore?’ It broke my heart.” That was when both parents were allowed to talk to their children for about an hour every weekend, something they no longer are allowed to have. “We just finished off our second permanency hearing, and now they’ve cut contact,” Robby said. “We’re not allowed to talk to the kids at all.”

Cama says her heart is broken. “This is more mentally and emotionally traumatizing than the situation before,” she cried. “My parents said that the kids cry for us. My 4-year-old, she does it every night. She’s got a picture in her bedroom of me, and she kisses it every night, and then they cry.”

Reading the Code

In this investigative series, just like Sherlock Holmes in the story “The Dancing Men,” we’ve been gathering more information to crack the code of why DFPS Commissioner Jamie Masters was fired.

Based on the records reviewed so far, the question no longer seems to be why was she fired, but what has been going on at DFPS, and for how long?

More importantly, why have Texans’ elected public servants allowed this madness by an incompetent and rogue state agency?

In Part 4 of this investigative series, Texas Scorecard will take a deeper look at DFPS and elected public servants’ failure to hold this out-of-control agency accountable.

No ads. No paywalls. No government grants. No corporate masters.

Just real news for real Texans.

Support Texas Scorecard to keep it that way!