Texas nearly leads the nation when it comes to local debt — a $332 billion albatross driving ever-increasing property taxes. Those who claim the growing debt crisis is the result of population growth aren’t telling the whole truth.

At nearly $12,000 per resident, Texans are burdened with the second-highest local debt liability in the nation. In other words, we rank second highest even after adjusting for our massive population growth. This staggering figure is only outpaced by New York, and is worse even than uber-liberal states such as California and Illinois.

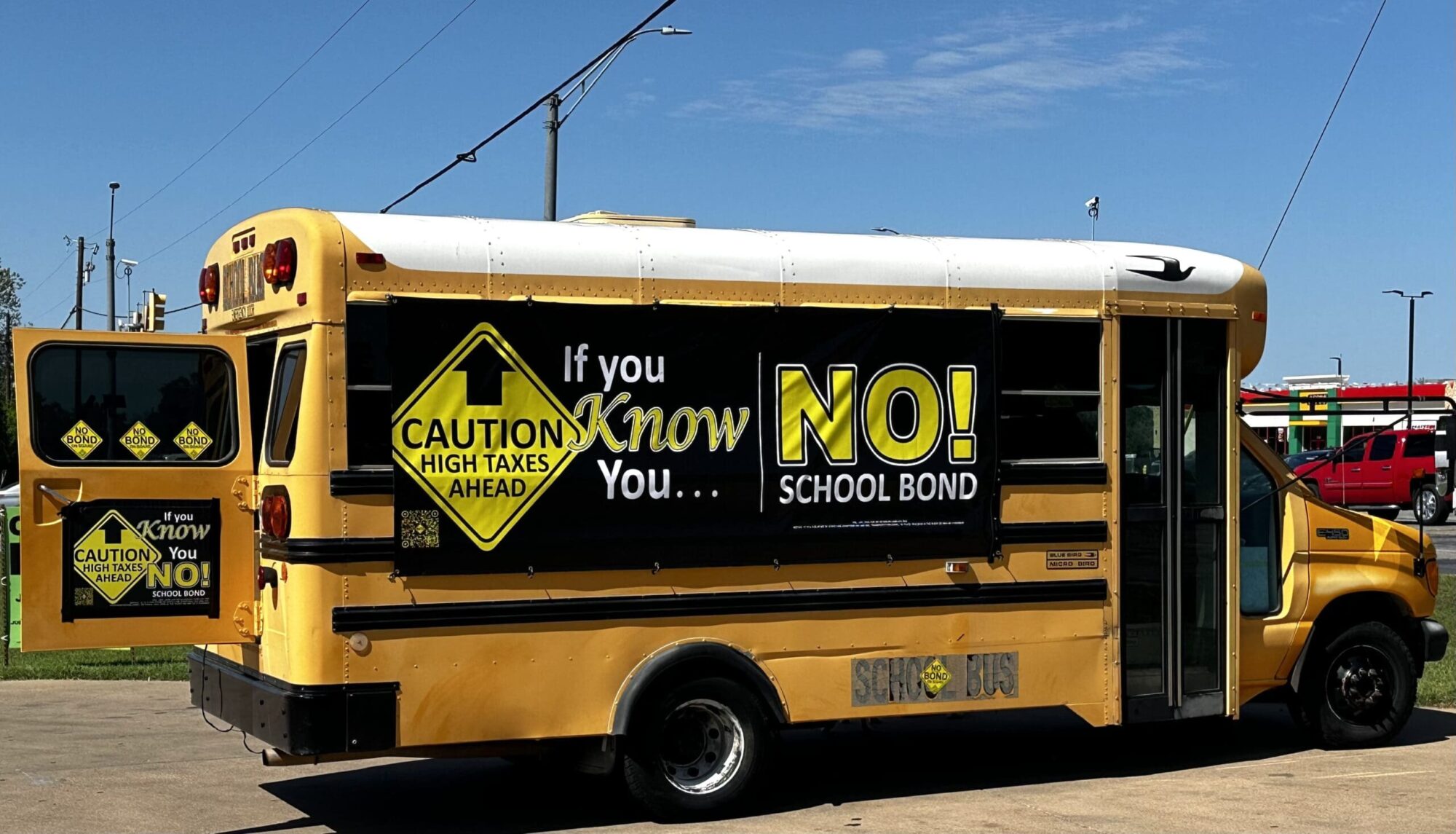

This November’s ballot will contain $8.8 billion in new debt proposals (excluding interest payments) — the highest cumulative price tag seen on a uniform election date in at least three years.

The problem is getting worse, not better.

So far, Texas state legislators from both parties appear indifferent about the problem. Even the historic tax relief package passed this session does little more than nibble around the edges.

If passed by voters this November, the constitutional amendment to increase the homestead exemption won’t provide a net tax cut for the average Texan—it will only slow the increase of their tax bill.

Undoubtedly, voters who fail to vote in local elections are enabling this crisis. But the legislature should assist them by passing common-sense reforms in three areas.

First of all, the legislature should limit the tax-hiking power of local politicians. Taxpayers would collectively save billions annually if their tax bills grew at a slower rate. After all, how many times has your property tax bill actually decreased?

The existing limit known as the “roll-back rate” isn’t really a limit at all. It only limits annual revenue growth, a metric that fails to account for changes in population, essentially treating no-growth and high-growth areas equally. It also fails to account for changes in the local tax base. Even worse, it’s a soft limit—with the exception of school districts, politicians can break it without seeking local voter approval.

Legislators should take a page from Houston citizens who voted to limit local officials in 2004, by putting a per capita growth limit in the city charter, a metric that accounts for all factors; changes in the tax base, population and appraisal values. The Senate passed a state-spending limit using the same metric this past session.

The second reform area is ballot transparency. Currently, voters do not see the total price tag of local debt proposals when voting, since the cost of interest and its impact on property tax rates is not disclosed on the actual ballot.

Last, basic changes to the debt issuing process would save taxpayers billions a year by limiting excess, waste, fraud and abuse. Local governments are essentially given a blank check for whatever dollar amount voters approve. The ballot language voters see is ridiculously ambiguous. Politicians are not required to report precisely how bond proceeds are spent, nor are they legally required to deliver what was promised to constituents in their glossy “informational” materials.

Governments should be required to use independent auditing firms that track debt-financed projects to compare what was promised versus what is actually delivered, and at what cost. Look no further than Houston ISD for a practical example of why the fox shouldn’t be trusted to guard the hen house.

There also needs to be limits on what debt can buy. Austin ISD was recently caught spending bond money on staff salaries, while districts across the state notoriously take on new debt to buy iPads, grandiose administrative facilities, unnecessary vehicles, security equipment and other items.

Before Texans can expect fiscal reforms, legislators must first acknowledge the debt crisis exists, and push for reforms to reach a floor vote in both chambers. But in order for that to happen, Texans need to contact their state and local officials and ask that both debt and tax reform become a legislative priority.