“This is going to be a train wreck, I think, to say the least.”

Judge Richard Evans, a Gov. Abbott-appointed board member to the Texas Indigent Defense Commission (TIDC), uttered these prescient words during an October 1, 2021, emergency meeting—a meeting called after the increase of arrests and bonding of illegal immigrants apprehended for criminal trespass during Abbott’s Operation Lone Star (OLS).

For months, the management of the military aspect of OLS has been criticized for soldiers’ paycheck hardships, bureaucratic turnover and inexperience at the Texas Military Department, supply issues, forced vaccinations, concerns about sexual assault, punishing soldiers through physical exertion, and the “toxic” management style of Abbott-appointee Maj. Gen. Tracy Norris. The ever-flowing streams of issues led to the charge that OLS is poorly planned “political theater.”

Adding to these woes, Texas Scorecard recently exposed problems with the judicial side of Operation Lone Star. In addition to those previously revealed issues, we’ve unearthed an overwhelmed system, potential conflicts with state law, and secret judicial proceedings.

Secret Judicial Proceedings

Kinney County, located about two hours west of San Antonio, borders Mexico and is a hotspot for illegal border crossings.

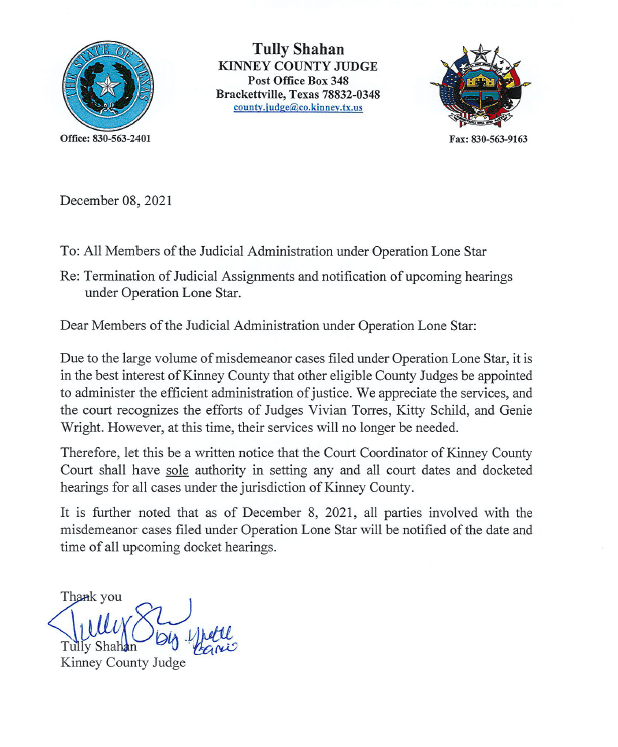

On December 8, 2021, Kinney County Judge Tully Shahan published a letter announcing the services of Judges Vivian Torres, Kitty Schild, and Genie Wright would “no longer be needed” for OLS cases. Shahan wrote, “It is in the best interest of Kinney County that other eligible County Judges be appointed.”

A day earlier, Kinney County Attorney Brent Smith filed a lawsuit asking that any further actions from Torres, Schild, and Wright be stopped. He alleged they had “granted some form of relief in” OLS cases “in ex parte communications without notice to the State and/or without conducting a hearing at which the State may be heard.”

Law.com explains “ex parte” is a Latin phrase meaning “for one party.” In the legal sense, it refers “to motions, hearings or orders granted on the request of and for the benefit of one party only.” Ex parte hearings are considered an exception to the standard of both parties being present before a judge, and that a lawyer must notify the opposing party before notifying a judge. Ex parte hearings usually involve temporary measures, “pending a formal hearing or an emergency request for a continuance.”

“In an ex parte hearing, the court is under a special burden to take into account the interests of the party that isn’t there,” attorney Tony McDonald told Texas Scorecard. “It’s only to be done when there is no alternative. And the burden for the moving party is always very high.”

Smith’s filing and additional communications suggest that Judges Torres, Schild, and Wright did not take into account the interests of the state when releasing defendants charged under OLS.

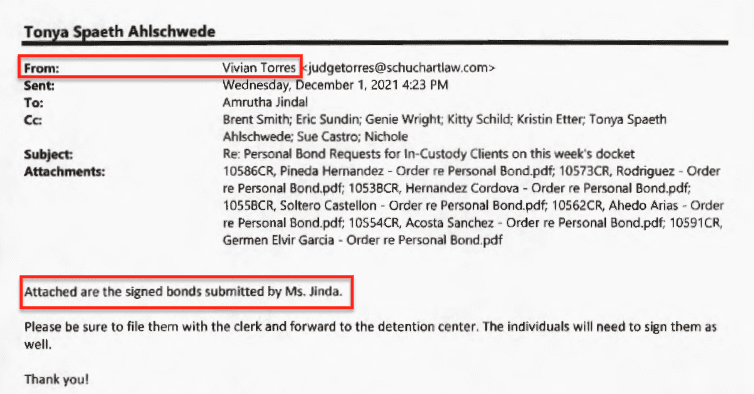

In his December 14 follow-up filing, Smith submitted what he argued was his evidence against the three judges. It contains three bonds and three waivers of arraignment, all signed on December 1, 2021.

The bonds were signed by Judge Torres, a Gov. Abbott appointee to the TIDC board.

On December 13, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals restricted the judges’ ability to act, pending a further court order, “except after the State has been given notice and an opportunity to be heard.”

After hearing allegations of suspicious activity regarding OLS judicial activities in the area during this time period, Texas Scorecard launched an investigation, sending open records requests to Kinney County and Judicial Rule 12 requests to Judges Torres, Schild, and Wright.

In late November and early December, events (namely illness) conspired that sidelined Judge Shahan and his court coordinator. This created an opening for the appointment of Judges Torres, Schild, and Wright by Judge Stephen Ables, the presiding judge of the Sixth Administrative Judicial Region.

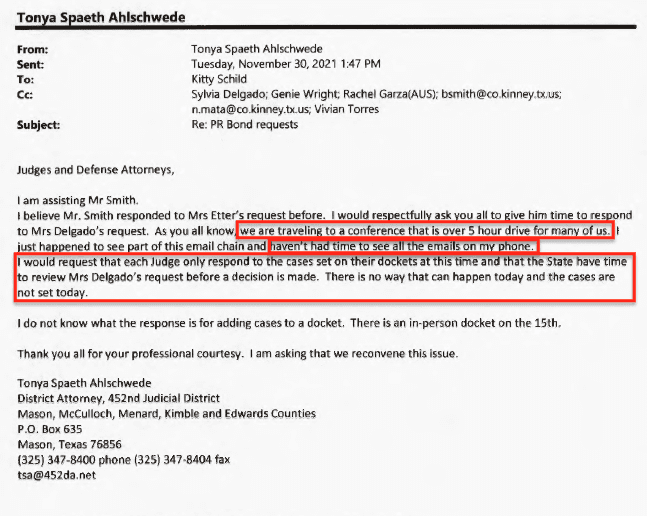

Kinney County Attorney Smith and District Attorney Tonya Ahlschwede (from the Border Prosecution Unit) were also away for a conference.

Ahlschwede, who had been assisting Smith with his OLS caseload, sent a follow-up email on November 30, reminding judges she and Smith were out of town and asking them to “only respond to the cases set on their dockets at this time.”

Her email was in response to a request by defense attorney Sylvia Delgado to get bonds for clients of hers who had been “in detention for more than the time permitted” by the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure. Delgado noted she wished to do so “in cooperation with the State.”

It appears Smith’s and Ahlschwede’s emails went unheeded.

The morning of December 1, defense attorney Amrutha Jindal, then of the Houston-based nonprofit Restoring Justice, asked Judge Torres to sign a number of bonds and waivers. This was a follow-up request from Jindal regarding clients who she wrote had been in jail for “almost 90 days” and had been scheduled for a December 2 hearing. That hearing was canceled due to County Judge Shahan’s and the court coordinator’s illnesses.

Hours later, Torres emailed the bonds back to Jindal without any apparent court hearing on the matter. Below is the email that contains the very bonds Smith alleged constituted “ex parte” communications.

Communications between judges and defense attorneys continued.

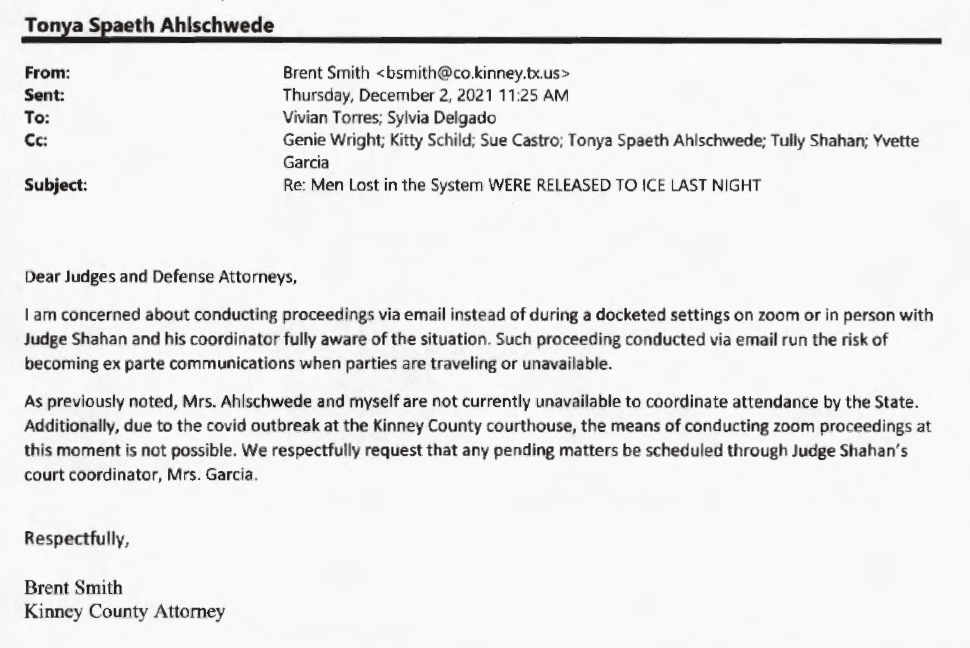

The next day, Smith again addressed both. “I am concerned about conducting proceedings via email instead of during a docketed settings on [Z]oom or in person with Judge Shahan and his coordinator fully aware of the situation,” he wrote. “Such proceeding[s] conducted via email run the risk of becoming an ex parte communications when parties are traveling or unavailable.”

“We respectfully request that any pending matters be scheduled through Judge Shahan’s court coordinator, Mrs. Garcia.”

Is it appropriate to hold those arrested in jail without a hearing for “almost 90 days”? State law says no, but in the era of COVID executive orders, it’s unclear if this portion of the law has been suspended or not.

Breaking State Law?

Abbott’s stated mission for Operation Lone Star is to help arrest illegal border crossers, not stop illegal border crossings. This made the courts an integral part of OLS, triggering important parts of state law.

First, the criminal charges that fall under OLS were clarified during the July 26, 2021, meeting of the board of the Texas Indigent Defense Commission. “My understanding are the primary offenses are criminal trespass, criminal mischief, smuggling, and human trafficking,” David Slayton told the board, responding to a question from TIDC board member State Rep. Nicole Collier (D–Fort Worth). Slayton is the vice president of Court Consulting Services for the National Center for State Courts.

In a December interview, defense attorney Sylvia Delgado gave Texas Scorecard insight into how OLS is being prosecuted. “[Suspects are] charged with criminal trespass, which is a misdemeanor,” she said. “Most of them are faced with Class A misdemeanors, because the border has been declared a disaster area, which bumped a regular Class B misdemeanor up to a Class A misdemeanor.”

Texas State Law states punishment for a Class A misdemeanor is a maximum fine of $4,000, a maximum of one year in jail, or both. For a Class B misdemeanor, it’s a maximum $2,000 fine, a maximum of 180 days in jail, or both.

State law has limits as to how long one can be held in jail while awaiting trial.

Article 17.151 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure states a defendant “must be released either on personal bond or by reducing the amount of bail required” if the state is not ready for trial within a certain amount of time, depending on the charge. For misdemeanors, where the punishment is more than 180 days of jail (Class A), the time limit is 30 days from the arrest. For less than 180 days (Class B), the limit is 15 days from the arrest.

Communications between lawyers and judges in Kinney County the week of November 28, 2021, which Texas Scorecard obtained through open records requests, revealed those arrested for criminal trespass under OLS have been in jail without a hearing longer than the code allows.

As noted in her email earlier, Delagdo wrote she had “many clients … in detention for more than the time permitted by the CCP.” She wasn’t alone. On November 29, 2021, Kristen Etter, taxpayer-funded Texas RioGrande Legal Aid’s (TRLA) special project director for OLS, informed judges she had clients who had been in jail for more than 90 days.

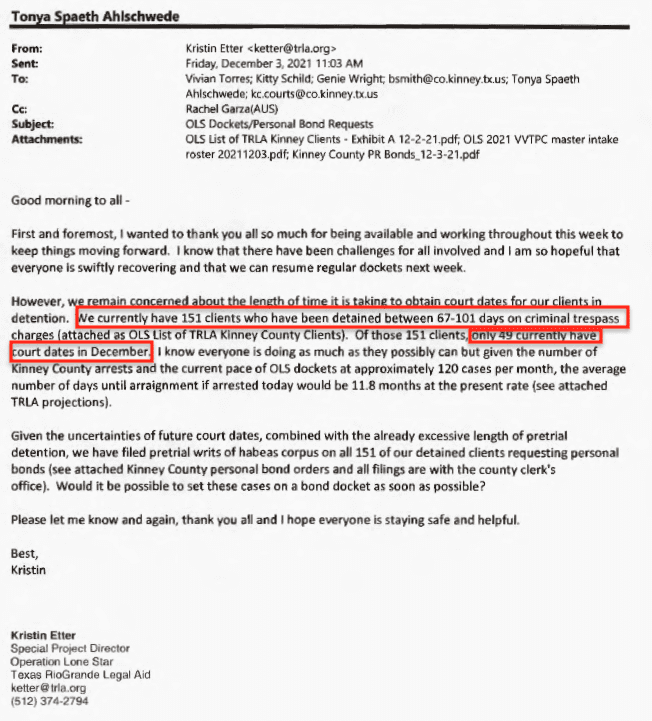

On December 3, Etter further informed judges that TRLA had “151 clients who have been detained between 67-101 days on criminal trespass charges,” and at the time, “only 49” had court dates that month.

The State Office of Court Administration did not respond to our request about how many arrested for criminal trespass under OLS had been held without a hearing longer than the code allows.

While these appear to be clear violations of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, there is disagreement on whether or not that portion of the law is in effect for OLS cases. None of the emergency orders issued by the Supreme Court of Texas regarding OLS mention any adjustments to Article 17.151.

In an internal TIDC July memorandum discussing what parts of state law to suspend for OLS, Article 17.151 was not mentioned anywhere. Texas Scorecard obtained this document through an open records request to TIDC.

Texas Scorecard asked Judge Ables and Kinney County Attorney Smith if this part of state law had been suspended.

“I don’t think so,” Ables replied. “I don’t think we have anything that’s overriding the code of criminal procedure.”

Smith pointed us to a March 20, 2020, executive order from Abbott. The order states that Article 17.151 of the TCCP “is hereby suspended to the extent necessary to prevent any person’s automatic release on personal bond because the State is not ready for trial.” However, this order was meant to stop the release of prisoners during the Chinese coronavirus situation. It isn’t clear whether or not Abbott’s order is still in effect or if it applies to OLS cases.

It appears as though Abbott—who served as state attorney general from 2002 to 2015—had not properly planned the judicial aspect of OLS, whose goal he had set to apprehend lawbreakers, not stop illegal border crossings.

This sent the Texas Indigent Defense Commission scrambling months after Abbott announced Operation Lone Star.

Rapid Funding Surge

Since July 2021, the TIDC board has allocated several tranches of taxpayer monies to the Texas RioGrande Legal Aid and indigent defense nonprofit Lubbock Private Defender Office. In August, LPDO’s role was explained as “handling all defense representation assignments, and services for attorneys along the border.”

TIDC’s August 2021 meeting book confirmed a working relationship between LPDO and TRLA. “Immediately following TIDC’s Board Meeting, LPDO initiated a remote managed assigned counsel model on July 28th, for the delivery of court appointed counsel and began assigning cases to Texas Rio Grande Legal Aid (TRLA),” the book reads.

LPDO is currently under suspicion after allegations surfaced that its chief defender, Philip Wischkaemper, was strong-arming attorneys to commit ethical violations in an effort to sabotage OLS, namely stopping defendants from entering guilty pleas.

TRLA lists the City of Austin as one of its supporters.

TIDC’s board has six Abbott appointees, one of whom is Judge Vivian Torres, who was present at last year’s July and October meetings. No one was heard voting against the monies for LPDO or TRLA at their July, August, and October meetings.

TIDC’s board also had to discuss a judicial system overwhelmed by Operation Lone Star.

Overwhelmed Judicial System

“I will tell you that this is not something that either [the Office of Court Administration] and TIDC staff can sustain,” David Slayton told the TIDC board during its July 26 emergency meeting.

Governor Abbott’s office, despite fighting the release of records outlining actions taken to manage indigent defense tied to OLS, is known to have been involved.

“The governor’s office reached out to the Office of Court Administration and to the Texas Indigent Defense Commission to ask for help in planning adjudication of these cases,” TIDC Executive Director Geoff Burkhart added, saying they had been in contact with Slayton and the governor’s office for “several weeks,” as well as Val Verde County officials, the Texas Department of Public Safety, and the commission on jail standards. “The impetus for this whole meeting today is that we genuinely don’t know that we can go through the next three to four weeks of cases.”

Texas Scorecard sent a request for TIDC’s communications with the Abbott administration about indigent defense for OLS. We sent a similar open records request to Gov. Abbott.

“It has been determined that the records you requested … are exempt from Rule 12, Texas Rules of Judicial Administration,” Wesley Shackelford, deputy director of TIDC, replied on February 14. Prior to this determination, which came five days after publication of our investigation into TIDC and LPDO, TIDC had been cooperating with our requests.

On February 15, Abbott’s office appealed to Attorney General Ken Paxton to withhold responsive documents.

Burkhart said during the July 26 meeting that they estimated “may be up to 200” OLS arrests a day and “approximately 73,000 arrests per year.” “That would be more than the cases adjudicated in Harris County in any given year.”

Slayton told board members that to handle that many arrests, four magistrates would need to work continuously for eight hours a day, seven days a week. The Texas Code of Criminal Procedure requires that within 48 hours of arrest, an individual be brought before a magistrate who informs him of his rights under the law, including his right to have an attorney provided to him if he can’t afford one.

Burkhart said the measures TIDC implemented that day was “triage,” and they’d be turning to LPDO and TRLA for help.

A review of this activity shows significant energy from Abbott in communicating and coordinating indigent defense, but Kinney County Attorney Brent Smith indicated not enough attention was given to the prosecution. “The defense was set up and ready to go before prosecutors,” he told Texas Scorecard. “The prosecution is very behind on getting the resources in place.”

During the October 1 board meeting, it became clear how overwhelmed Kinney County had become. “All these cases are prosecuted locally, and when you look at some of these counties, for instance, the county attorney in Kinney County … frankly, [he] was just overwhelmed by the volume,” Burkhart told TIDC board members. He explained the Border Prosecution Unit, “kind of a … loose affiliation of 17 different DAs” across the border “that work and kind of share resources,” came to help Smith. “One of the issues was that those cases were not being charged initially, and so things were starting to backlog a little bit.”

TIDC also discovered an issue with an insufficient number of judges available for OLS. “I know that the [presiding judges] were having issues with trying to get enough visiting judges to be able to do the 1,517 hearings,” said TIDC board member Judge Missy Medary.

When the topic of bonds was broached during the October meeting, Judge Evans asked, “We will release on PR bonds after the appropriate time, is that correct?” TIDC Executive Director Burkhart replied, “Correct.”

“They’ll be out on PR bonds. This is going to be a train wreck,” Evans said.

Open Courts and “Ex Parte”

A review of state law, and the rapid surging and scrambling of state bodies to deal with Operation Lone Star, brings us back to the situation in Kinney County last November and December.

The number of days arrested illegal immigrants are being held in jail without a hearing mentioned in attorney’s communications with Judges Torres, Schild, and Wright are well beyond the time limit set by the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure. However, aside from Smith’s allegation of “ex parte” communications, there is another issue to consider; these bonds were submitted and signed by email, instead of in a court hearing where citizens can witness. This raises questions of whether the Texas Constitution’s open courts requirement was violated, which is worded as follows:

All courts shall be open, and every person for an injury done him, in his lands, goods, person or reputation, shall have remedy by due course of law.

Texas Scorecard obtained the email communications of these bond negotiations and signings through open records requests. To our knowledge, these emails were not publicly posted for citizens to easily access.

We asked Judge Torres if signing bonds over email violated the open courts requirement. “First and foremost, these were not hearings, nor were they court proceedings,” she replied. “Bond issues arise all the time, and the public does have access to it because they can access the court file and see what the bonds are, and any matters that are involving the case.”

“Open courts means that the courts are available to litigants in order to file cases and file suits. You can’t do anything to interfere with a person’s access to seek redress in a court of law,” she continued. “Public access means that the public has the right to access court records or proceedings, and it is easy for them to do so.”

Texas Scorecard asked Judge Ables, who assigned Torres to help Shahan, if it was normal to sign bonds over email instead of in an open court hearing.

“I don’t know, I’m not sure, but that can happen,” he replied. Ables relayed that during the pandemic court administration was upended, with hearings conducted over the phone or by Zoom. While some jurisdictions have returned to normal, allowing the public to witness court proceedings, it’s unclear if streamlining practices have ended across the board.

The State Office of Court Administration did not respond to our inquiry on this matter.

Judge Torres bristled when asked if her actions could be construed as ex parte.

“I don’t know where you get your information, but I know you’re familiar with email, and we all have it on our little phones that we carry everywhere we go,” she replied. “They were included in every communication. In fact, Mr. Smith sent language that he did not oppose the bonds. If they said they needed time to review something, they were given time to review it. There was nothing ‘ex parte.’”

County Attorney Smith’s email from December 2 stands in direct contradiction to Torres’ recollections.

Defense Attorneys Fight to Bring Back Judges

Judge Ables explained that while Torres, Schild, and Wright are still assigned to Kinney County, County Judge Shahan has since opted to turn to county judges from adjoining counties. “After he got back to work and got over his illness, he decided to use the provision in the Constitution where he can use county judges from adjoining counties to help him.”

On December 9—one day after Shahan announced Torres, Schild, and Wright would no longer be used—Texas RioGrande Legal Aid Executive Director Robert Doggett and Kristin Etter sent a letter to Judge Ables. “We ask that you renounce Judge Shahan’s attempt to exercise authority vested only in you as the presiding judge of Administrative Region 6 … and not permit any further disruption to the hearings currently scheduled, or the dockets that were established before his Dec. 8 letter.”

They wrote TRLA was representing 153 clients at the time, and most were set to have hearings before Torres and Schild. “They are finally on dockets for December before one of the assigned judges whose authority has been called into question by Judge Shahan’s attempt to remove them.”

Judge Ables demurred from TRLA’s request. “Upon his return from Covid[,] Judge Shahan let me know he was ready to resume handling cases in his court. As the judge of the court he has that prerogative,” he replied in a December 9 email. “I informed the three judges that [they] would not be needed anymore since Judge Shahan has returned. As you know, I can only assign judges pursuant to a request from the elected judge.”

On December 22, two separate lawsuits were filed by Austin-based criminal defense attorneys Keith Hampton, Angelica Cogliano, and Addy Miro. The lawsuits sought to force Shahan to bring Torres, Schild, and Wright back onto OLS cases in Kinney County, but they were rejected on February 16, 2022.

Texas Scorecard asked each attorney, in regard to their Operation Lone Star cases, if they were working for, ever worked for, or had been recruited by the taxpayer-funded Lubbock Private Defender Office. Only Cogliano replied, stating she was then representing “some individuals as an independent contractor for” LPDO.