A federal judge’s ruling in Galveston County’s redistricting trial will impact how voting districts are drawn across Texas, from school districts to the state legislature.

Courtroom proceedings concluded Friday with the county’s legal team outlining to the judge how the plaintiffs failed to prove their case.

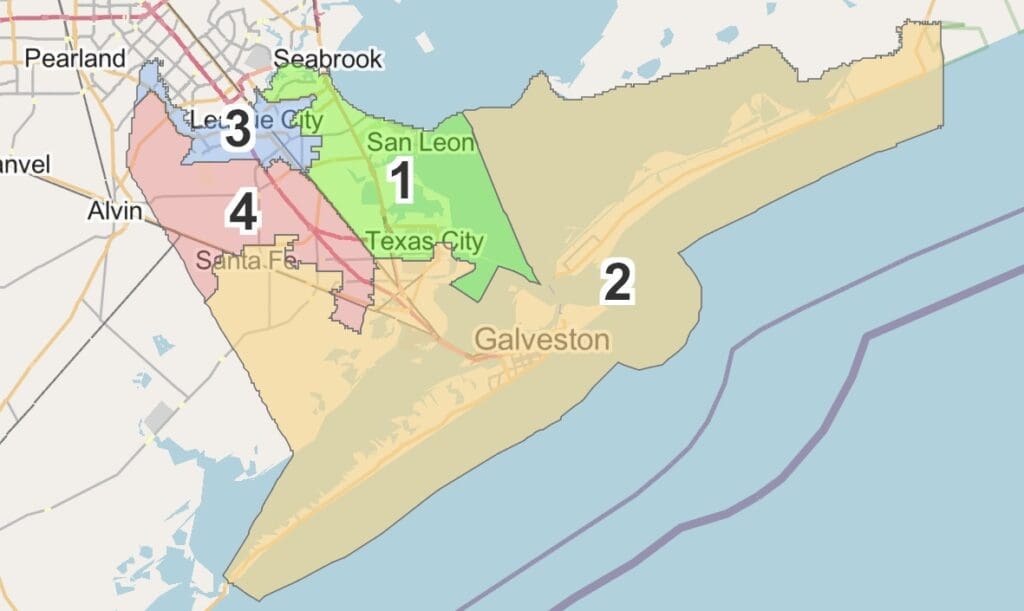

The trial centered on challenges to a map of commissioner precincts adopted by the Galveston County Commissioners Court in 2021.

A group of plaintiffs in three consolidated lawsuits accused the county of intentional racial discrimination because the county’s lone majority-minority commissioner precinct was eliminated.

U.S. District Court Judge Jeffery V. Brown presided over the two-week trial in Galveston.

“Plaintiffs have the burden of proof,” said attorney Joseph Russo, a member of the county’s legal team, after the final witness testified.

Russo told Judge Brown the plaintiffs failed to provide evidence that race was a predominant factor in drawing new precincts, which is required to prove racial gerrymandering under the 14th Amendment.

He also argued they did not meet the legal tests required under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act to show a majority-minority district should be created.

“The Constitution gives Texas the power to do their own redistricting,” said Public Interest Legal Foundation President Christian Adams, another member of the county’s defense team, who spoke to the “totality of circumstances” plaintiffs must show to prove a Section 2 violation.

“Only in rare cases, like the Voting Rights Act, and after the plaintiffs carry a heavy burden of proof, may federal law dictate to Texas,” Adams said. “Plaintiffs have not carried that burden at all.”

The plaintiffs are the U.S. Department of Justice, local chapters of the NAACP and League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), and a group of current and former local office holders. The three suits were consolidated as Petteway v. Galveston County.

Plaintiffs sued after the county redrew district lines following the 2020 Census to rebalance the population equally among the four commissioner precincts.

Precinct 3, represented by the county’s lone Democrat commissioner, changed from being the only majority-minority precinct to majority Anglo after the redraw.

One of the plaintiffs’ expert witnesses testified during the first week of the trial that the county’s redistricting plan was a “textbook case of racial gerrymandering.”

During the second week of the trial, defense witnesses—including the demographer who drew the new precinct boundaries—testified that race “was not in any way a factor” in creating the maps.

Neither black nor Hispanic residents are a large enough percentage of Galveston County’s population to create a single-minority district. Growth in the county since 2010 has been predominantly Anglo and Republican, making it more difficult to maintain a safe-Democrat minority district.

The county’s 2011 map was racially gerrymandered under the now-defunct Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, after the DOJ objected to the county’s original plan under Section 5’s “preclearance” regime.

Dale Oldham, who served as legal counsel to Galveston County commissioners during their 2011 and 2021 redistricting, said the county avoided replicating the now-impermissible racial gerrymander by drawing lines based on non-racial data.

Plaintiffs pointed to the 2011 objection as proving a history of racial discrimination.

But Adams, who is also a former DOJ Voting Section attorney and now serves on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, responded, “An objection under the old Section 5 mandates, which the Supreme Court struck down as unconstitutional, is not proof of discrimination.”

“The Court held Texas shouldn’t even be subject to the preclearance requirement,” said Adams.

While Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act is no longer operative, Section 2 remains intact, prohibiting voting practices—including redistricting—that discriminate on the basis of race.

Racially polarized voting is one of the legal preconditions for requiring a majority-minority district under Section 2.

Plaintiffs’ experts testified that the county’s elections are racially polarized.

But an expert witness for the defense rebutted their conclusions.

John Alford, a Rice University political science professor who specializes in elections and voting behavior, testified that voting in Galveston County elections is polarized by party, not by race. Alford said black and Hispanic voters vote strongly for Democrat candidates and Anglos vote strongly for Republican candidates—regardless of the candidates’ race.

“What we see is a very classic pattern of polarization… a partisan polarization,” he said.

Also at issue is whether black and Hispanic voters can be grouped together as a single minority to meet the requirement for a majority-minority district to be created.

Galveston County’s case is challenging old rulings from the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals (which hears cases from Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi) that have allowed such “coalition” districts.

Other federal circuits do not allow using minority group coalitions to create what are almost always Democrat districts.

If Galveston prevails in its challenge to coalition districts, Democrats are likely to lose seats in the Texas Legislature and across all levels of government.

Defendants have indicated they want to push the issue at the Fifth Circuit to reverse decades of race-centric line-drawing in Texas. It could be brought to the U.S. Supreme Court if necessary, where they believe at least five Justices would be persuaded by Galveston’s argument.

“This is a very important case,” Judge Brown said at the trial’s conclusion.

Post-trial filings are due to the court on September 8 and 15, then the parties will await the judge’s ruling.

Meanwhile, commissioner Precincts 1 and 3 are on the November 2024 ballot. The filing period for candidates to run in the primary for those seats is November 11-December 11, 2023.