On the campaign trail, a Republican congresswoman seeking hundreds of millions in taxpayer funds for a real-estate project run by her son is claiming a study justifying it was completed. The problem is that the representative knows the study never happened.

For infrastructure projects to earn federal support, they must undergo a cost-benefit analysis by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. These studies demonstrate a project’s need and justify its cost to Congress and taxpayers.

After nearly 14 years and $400 million spent, Fort Worth’s Panther Island project pushed by U.S. Rep. Kay Granger (R–Fort Worth) has never undergone such a study.

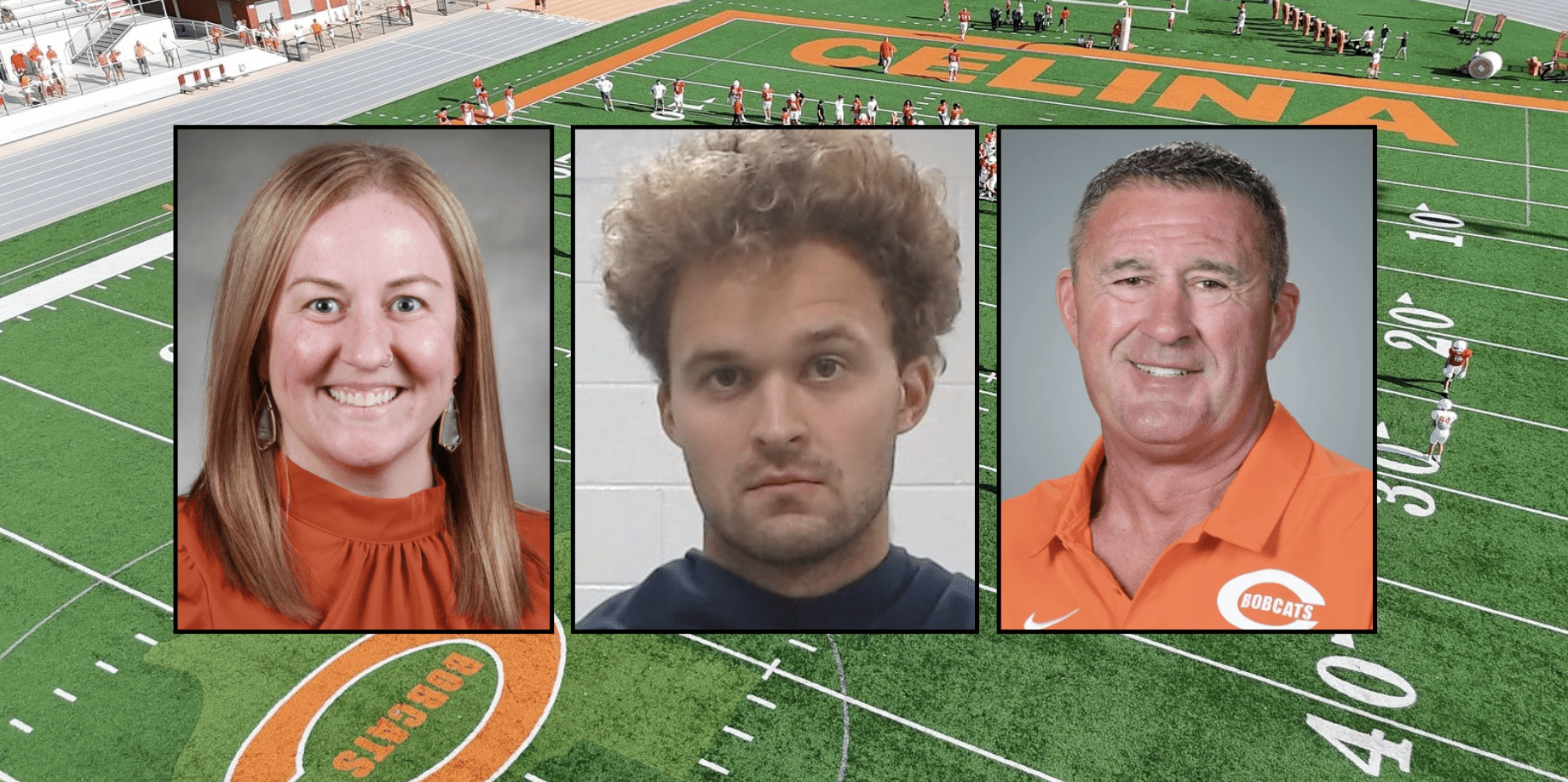

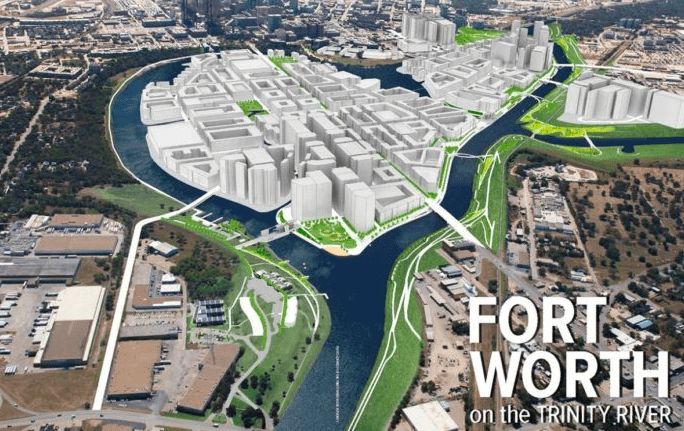

Granger’s $1.2 billion plan seeks to reroute the Trinity River via a bypass channel—and redevelop Fort Worth real estate—all under the guise of “flood control.” It launched in 2006 with Granger’s support as a ranking member of the powerful House Appropriations Committee. Her unqualified son, attorney J.D. Granger, was hired to oversee the project.

Granger’s son remains employed as executive director at a $250,000 annual cost to taxpayers, despite the troubled project running $800 million over budget.

For 13 years, the congresswoman has worked—mostly unsuccessfully—to funnel hundreds of millions in federal tax dollars to the scheme. But with problems mounting, and Granger facing a primary challenge from conservative businessman Chris Putnam, it’s attracting more scrutiny than ever before.

In addition to Panther Island’s mismanagement and nepotism, its core problem is that it’s unnecessary and shouldn’t be receiving any taxpayer funding. Critics have long claimed no flood risk exists along the Trinity River in Fort Worth, and the fact that a flood study was never done all but proves they’re correct.

But Granger has been overheard telling voters a different story on the 2020 campaign trail. Texas Scorecard asked her directly for comment about if a flood study has been done, and where it is located.

“Of course there has,” Granger insisted. “I’m sure the water district has it. The Corps of Engineers did that. … They can’t do [the project] without a study. The Corps of Engineers said you’ve got a flood control problem. You can’t maintain the floods, and so, the city [of Fort Worth asked], ‘What do we do?’ And so, I think it was a seven-year study, and they came back and said, ‘Here’s what you do.'”

Unfortunately for Granger, we know she’s not telling the truth.

The Texas Monitor published an investigative report in October 2018 that revealed the Corps halted federal funding to Panther Island specifically because no sufficient study had been completed. Records also show that Granger, her son, and Panther Island’s employees knew the study hadn’t been done. In fact, they fought the requirement out of fear that it would tank the project.

A review of emails by the Monitor showed that officials knew since 2010 that the Corps would require a study.

As of 2010, the project had been limping along on mostly state and local tax dollars for four years. The Grangers tried to use an economic impact study of the development to circumvent the requirement, but the Corps said it wasn’t sufficient because it didn’t review the flood issue.

When federal lawmakers introduced a provision in 2016 requiring a cost analysis tied to $526 million in federal funds—roughly half of Panther Island’s price tag—the Grangers panicked. Requiring such an analysis, one consultant wrote to them, would be “devastating” to the project, the Monitor reported.

“We need to make double sure the House doesn’t roll on this,” the consultant wrote to J.D. Granger.

“We are all over it and will make sure the House conferees know [the study requirement] is a deal killer,” Rep. Granger wrote to a staffer.

The Grangers managed to get the study requirement removed from the 2016 spending bill. But since the Monitor’s 2018 report was published, federal funding has not been restored, thanks to a litany of new problems.

As Granger’s agency concedes in a timeline on its website, a major flood event has not overrun the current levee system since the Corps completed it in 1957. The last severe floods were in 1922 and 1949; the Trinity River became a “dry, littered ditch” since the 1960s.

This is why critics were first suspicious in 2006 that Granger’s true motivation was real-estate redevelopment. The pretense of flood control was simply created so taxpayer money could be improperly used to subsidize development.

Panther Island’s website even emphasizes that its flood control aspects are needed to develop “underutilized” land and replace the current levee system, rather than augment it:

“The infrastructure constructed as a part of the Central City will eliminate the need for our current levee system – resulting in access right up to the waterfront. … The bypass channel and associated infrastructure will aid in restoring more than 800 acres of underutilized land resulting in opportunities for over 10,000 housing units and over 3 million square feet of commercial, retail and educational space.”

In other words, the $1.2 billion cost to reroute the river and build three bridges, a dam, several flood gates, and a water storage reservoir is only needed to create new waterfront real estate, all of which currently resides in a desolate and largely worthless flood plain.

Photo: The Texas Monitor

Today’s levy system works, and there is no hard evidence to suggest otherwise. The “problem” is that it only provides flood protection to the surrounding area while allowing flooding on the property targeted by the Grangers for redevelopment.

A misleading $250 million “flood control” bond was approved by voters in 2018 to keep Granger’s scheme on life support in case federal funds were delayed past 2019. They were.

A third-party review was released in early 2019 that revealed dysfunctional management by Granger’s son and his ally, Jim Oliver. The review found the two kept the agency’s board members in the dark about rampant problems.

After 13 years and more than $390 million in federal, state, and local tax dollars spent, no single aspect of construction was complete, according to the report. The project’s most visible eyesores remain three unfinished bridges over dry land.

Sources told Texas Scorecard the Texas Department of Transportation has forked over additional state funds to cover for the mistake, yet the bridges remain unfinished after five long years.

In the 2019 review, Granger’s agency claimed Panther Island’s design phase was “100 percent complete,” but Texas Scorecard later discovered that to be false.

At a recent board meeting, officials stated that certain design aspects were less than 60 percent complete. The agency’s newest consultant, hired for $25,000 per month, told Fort Worth’s city manager the exact figure was “unknown.”

With problems mounting, federal funding halted, and Granger facing a tough challenge from Putnam, the congresswoman has sadly resorted to falsehoods on the campaign trail.

After 20 years since Granger’s $1.2 billion real-estate scheme was first conceptualized, taxpayers still have no shred of evidence that it’s needed for flood protection and worthy of any amount of taxpayer funding.